This is the story of a dish whose origin is rooted in people’s own heritage and centennial tradition. It is the story of a dish that was born to be rare and precious, because prepared only and exclusively to honor the holy worship of a saint. It is also the story of a family and how it managed so far to maintain a special sliver of culinary art alive, all on its own.

And finally, it is, we hope, the story of how today’s effort to protect our cultural heritage, also in the kitchen, may save this dish from disappearing for ever. The last word on that, however, has yet to be written.

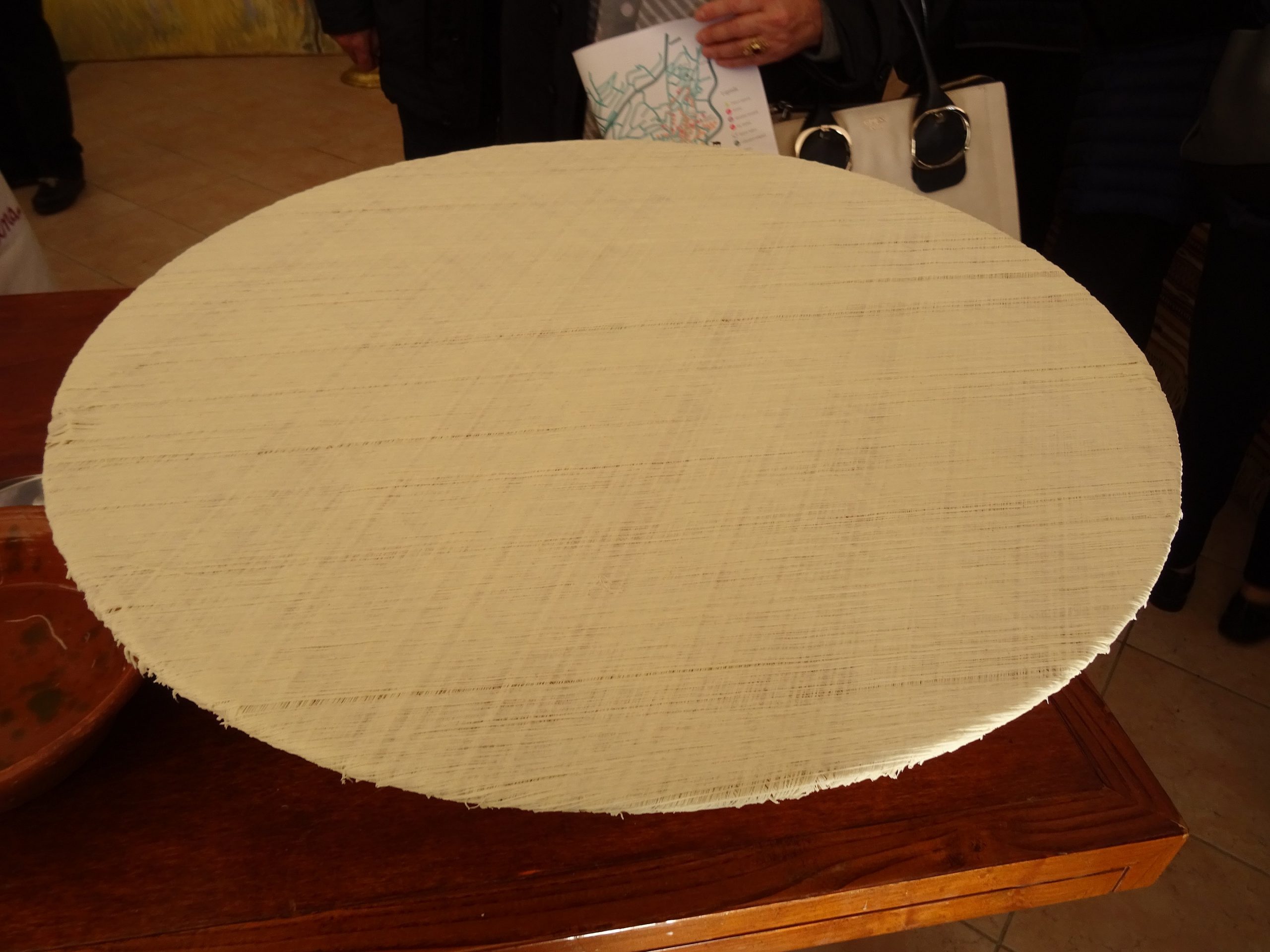

Su filindeu – the threads of God, literally – remind closely, in look and color, of another jewel of Sardinian tradition, byssus, that see-through, fragile silk of the sea so extraordinary and valuable to be used only to make garments for Popes and Kings: the color of blanched seashells, their weft regular and delicate, both are fragile and made by skilful hands, nowadays as valuable as the product they create. Indeed, there are only three women, all in the Nuoro area, who are able to make su filindeu and they all belong to the Abraini family: why, you ask? Because it’s within this family that, for more than 300 years, the art of making the threads of God has been exclusively kept, cherished and protected, passed on from mother to daughter all the way to our times.

You see, su filindeu have never been an ordinary pasta and their story is as charming as you would expect. It all started in the small town of Lula, which have been celebrating its patron saint, Francis, twice a year for centuries, in October and May. In both occasions, the faithful embark in a 33 km long pilgrimage from Nuoro to Lula, a way to pray and reflect as ancient and the feast itself: it is in this context that su filindeu was born, as the dish to offer to pilgrims once they reached Lula after their 8 hour long trek through the hills. They were served, and still are today, in a sheep broth, topped with pecorino sardo cheese, a earthly reward after so much spiritual yearning.

But what makes su filindeu so special is not only the fact they are eaten only twice a year, but also how difficult they are to make: starting from a simple mix of water, flour and salt, the dough is kneaded, divided in sections and rolled into cylinders which are then pulled and folded many times, until they are transformed in 256 threads about half the width of angel hair.

The whole process is not only painstakingly long – it can take up to a month of full time work to make about 100 lbs of pasta – but also incredibly difficult. To say it is Paola Abraini, one of the only three women still able to make su filindeu from scratch, who is in charge of most of their production; she has become, in recent years, a bit of a celebrity, especially after Jamie Oliver went to visit her in an attempt to learn her art. With no avail. Following Jamie’s adventures, BBC Food got interested in her and made her a VIP among international foodies. To British journalist Eliot Stein, she declared that the secret to make perfect su filindeu is “understanding the dough with your hands,” a process that can take years to master, a “game with your hands, but once you achieve it, then the magic happens.” If the dough is too dry, she dips her fingers in a bowl of cold water; if it needs more elasticity, she does the same in one of salted water.

A game with the hands it may be, but a very hard one to master, even for the world of engineering: experts from Barilla visited Mrs Abraini to see whether her technique could be reproduce by machines, but they found it way too complex, leaving the hope to keep the tradition and art of su filindeu alive, quite literally, in the hands of those eager to learn how to make them.

As said, the Abrainis have been passing on their special skills for generations, but Paola’s daughters have shown little interest in learning, with only one of them knowing the basics of the process, so it became adamant the tradition needed to reach outside the family to remain alive. Paola did suggest the creation of a special school where she could teach su filindeu making, but lack of funding made the project impossible to complete and resorted to teach in her own kitchen to whomever was interested: unfortunately, in a world where only the fast and the disposable count, Paola’s intricate, slow art failed to attract and maintain the interest of her students alive for more than one session. Making su filindeu is, indeed, an art at risk, as also stated by the people of the Ark of Taste, an initiative lead by Slow Food International aiming at cataloguing and protecting the world most endangered foods.

Mrs Abraini, though, is a tough cookie and is far from surrendering: she wants su filindeu to survive. For this reason, she has been trying to make them more popular outside of the Nuoro area, in the hope someone will show an interest in learning her skills. She has teamed up with Gambero Rosso, Italy’s most prestigious food magazine, to make a documentary about the su filindeu making process, and has also been supplying the pasta to three restaurants, the Agriturismo Testone and two eateries in downtown Nuoro, Il Rifugio and Al Ciusa.

The hope is that, beside loving the way they taste, someone also gets the urge to learn how to make them, allowing the amazing skills of the Abrainis to remain alive for another 300 years at least.

Questa è la storia di un piatto la cui origine è radicata nell’eredità della gente e nella tradizione centenaria. È la storia di un piatto nato per essere raro e prezioso, perché preparato solo ed esclusivamente per onorare la sacra adorazione di un santo. È anche la storia di una famiglia e di come è finora riuscita a mantenere vivo uno speciale frammento di arte culinaria, tutta da sola.

Ed infine è, speriamo, la storia di come lo sforzo odierno di proteggere il nostro patrimonio culturale, anche in cucina, possa salvare questo piatto dallo scomparire per sempre. L’ultima parola su questo, tuttavia, deve ancora essere scritta.

Su Filindeu – letteralmente, i fili di Dio – ricordano da vicino, per aspetto e colore, un altro gioiello della tradizione sarda, il bisso, quella trasparente, fragile, seta di mare così straordinaria e preziosa da essere usata solo per confezionare abiti per i Papi e i re: il colore delle conchiglie scolorite, la loro trama regolare e delicata, entrambi sono fragili e fatti da mani sapienti, oggi preziose come il prodotto che creano. In effetti, ci sono solo tre donne, tutte nell’area di Nuoro, che sono in grado di fare Su Filindeu e appartengono tutte alla famiglia Abraini: perché, chiederete? Perché è all’interno di questa famiglia che, per più di 300 anni, l’arte di creare i fili di Dio è stata esclusivamente custodita, amata e protetta, trasmessa da madre in figlia fino ai nostri tempi.

Vedete, Su Filindeu non è mai stata una pasta ordinaria e la sua storia è affascinante come ci si aspetterebbe. Tutto è iniziato nella piccola città di Lula, che per secoli ha celebrato il suo santo patrono, Francesco, due volte l’anno, in ottobre e maggio. In entrambe le occasioni, i fedeli si imbarcano in un pellegrinaggio di 33 km da Nuoro a Lula, un modo per pregare e riflettere come in passato e sulla festa stessa: è in questo contesto che è nato Su Filindeu, un piatto da offrire ai pellegrini una volta che avevano raggiunto Lula dopo 8 ore di viaggio attraverso le colline. Erano serviti, e lo sono ancora oggi, in un brodo di pecora, conditi con formaggio pecorino sardo, una ricompensa terrena dopo tanto desiderio spirituale.

Ma ciò che rende il Su Filindeu così speciale non è soltanto il fatto che vengono mangiati solo due volte l’anno, ma anche quanto siano difficili da fare: partendo da un semplice mix di acqua, farina e sale, l’impasto viene impastato, diviso in sezioni e arrotolato in cilindri che vengono poi tirati e piegati molte volte, fino a quando non vengono trasformati in 256 fili di circa la metà della larghezza dei capelli d’angelo.

L’intero processo non è solo faticosamente lungo: può richiedere fino a un mese di lavoro a tempo pieno per produrre circa 100 libbre di pasta, ma anche incredibilmente difficile. A dirlo è Paola Abraini, una delle sole tre donne ancora in grado di fare il Su Filindeu da zero, che è responsabile della maggior parte della loro produzione; è diventata, negli ultimi anni, una celebrità, specialmente dopo che Jamie Oliver è andata a farle visita nel tentativo di imparare la sua arte. Senza successo. Seguendo le avventure di Jamie, la BBC Food si è interessata a lei e l’ha resa un VIP tra i buongustai internazionali. Alla giornalista inglese Eliot Stein, ha dichiarato che il segreto per fare perfetti Su Filindeu è “capire l’impasto con le mani”, un processo che può richiedere anni prima di essere padroneggiato, un “gioco con le mani, ma una volta appreso, la magia accade”. Se l’impasto è troppo secco, immerge le dita in una ciotola di acqua fredda; se ha bisogno di più elasticità, si fa lo stesso in acqua salata.

Può essere un gioco con le mani, ma molto difficile da padroneggiare, anche per il mondo dell’ingegneria: esperti della Barilla hanno fatto visita alla signora Abraini per vedere se la sua tecnica potesse essere riprodotta dalle macchine, ma l’hanno trovata troppo complessa, lasciando la speranza di mantenere viva la tradizione e l’arte di Su Filindeu, letteralmente, nelle mani di coloro che sono desiderosi di imparare a realizzarli.

Come detto, gli Abraini hanno trasmesso le loro speciali abilità per generazioni, ma le figlie di Paola hanno mostrato scarso interesse nell’apprendimento, con solo una di loro che conosce le basi del processo, quindi è diventato indispensabile che la tradizione esca dalla famiglia per sopravvivere. Paola ha suggerito la creazione di una scuola speciale dove lei poteva insegnare a fare il Su Filindeu, ma la mancanza di fondi ha reso il progetto impossibile da completare e si è ridotta a insegnare nella sua cucina a chiunque fosse interessato: purtroppo, in un mondo in cui conta solo il veloce e l’usa e getta, l’intricata e lenta arte di Paola non è riuscita ad attrarre e mantenere vivo l’interesse dei suoi studenti per più di una sessione.

Fare il Su Filindeu è, in effetti, un’arte a rischio, come affermato anche dal popolo dell’Arca del Gusto, un’iniziativa guidata da Slow Food International che mira a catalogare e proteggere gli alimenti più minacciati del mondo.

La signora Abraini, però, è un tipo tosto ed è ben lontana dall’arrendersi: vuole che il Su Filindeu sopravviva. Per questo motivo, ha cercato di renderlo più popolare al di fuori dell’area di Nuoro, nella speranza che qualcuno mostri interesse nell’apprendere le sue capacità. Ha collaborato con il Gambero Rosso, la più prestigiosa rivista alimentare italiana, per realizzare un documentario sul processo di produzione del Su Filindeu, e ha anche fornito la pasta a tre ristoranti, l’Agriturismo Testone e due ristoranti nel centro di Nuoro, Il Rifugio e Al Ciusa.

La speranza è che, oltre ad amare il modo in cui si gusta, qualcuno abbia anche la voglia di imparare come farlo, permettendo alle incredibili abilità degli Abraini di sopravvivere per almeno altri 300 anni.