This is a novel that is laced with the bitterness and sweetness that characterizes Sicilian history. It’s an historical novel that finds a place between Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard and Dacia Maraini’s more recent The Silent Duchess.

Anthony Di Renzo sets his well-written and engaging novel in 19th century Sicily on the cusp of the birth of the modern Italian state, as Italy struggles to move into the modern, industrial era while still bound by the politics and culture of its history. Trinàcria portrays the cynicism and discouragement that characterizes so much of Sicilian writing over the last one-hundred and fifty years. It is a novel that oscillates between illusion and reality, between hope and pessimism.

What, after all, will ever change in Sicily, the gem of the Mediterranean? How will Sicilians ever rid themselves of their long history of subjugation? Di Renzo, who teaches writing at Ithaca College in New York, understands that, as one of his characters says, “The past never dies in Sicily.” The history of Sicily is a history of invasion, from the Greeks and Arabs and Bourbons to the Germans and Americans.

Appropriately, the novel opens with the most resent post-war invasion, Hollywood and the American film industry. A film crew is in Palermo to make yet another historical epic on the scale of Cleopatra or Ben-Hur.

Ironically the most oppressive invasion comes at the hands of the Italian North, when Garibaldi and his Red Shirts stormed through Sicily, ran out the last of the Bourbons, and unified Italy. But as Di Renzo so convincingly dramatizes, this for Sicilians is just another invasion, a violation of their free will, their right to a quiet enjoyment of their history and culture.

The main character and narrator of the novel is Zita Valanguerra Spinelli, the Marchesa di Scalea. Di Renzo tells us in an afterword that she is a composite of two historical figures. Adding to the historical layers of his novel, Di Renzo has her narrate the action of the novel from the grave, to be specific, from the Catacombs of the Capuchins in Palermo where she has been entombed. Her cynicism, disbelief, and distrust of all men pervade the novel.

As a woman with little power in Sicilian society and as the last standing representative of an older way of life, she is forced to be a helpless spectator as history has its way with her. She inherits an estate near Palermo. As she says, the bequest of land “pleased me, for I was fiercely attached to the Conca d’ Oro, the honey-colored plain surrounding Palermo.” But in time her wealth diminishes. Her villa falls into disrepair, and her only heir is a weak-willed son who does not understand the forces of history that have overtaken his family.

The Marchesa is called Trinàcria, a sign that identifies her with the roots of pagan Sicily. When the Red Shirts take control of the island, they invade her estate and begin what Garibaldi’s forces call the leveling of the populace. If everyone cannot afford to ride, an officer tells her, then everyone must walk. She is forced to watch helplessly as the officer takes an ax to her family’s historic carriage and reduces it to kindling before her eyes. Her heritage lies in ruins at the hands of the invading force of the new, modern Italy. The fearless Marchesa physically assaults the officer and has to be violently restrained. This is not the last time that she acts. For those of us who have family from the South of Italy, we have all known such women from the peasant class. Di Renzo’s Zita is fictional but not fanciful. Her outspokenness and aggression is credible, even for a woman of her times.

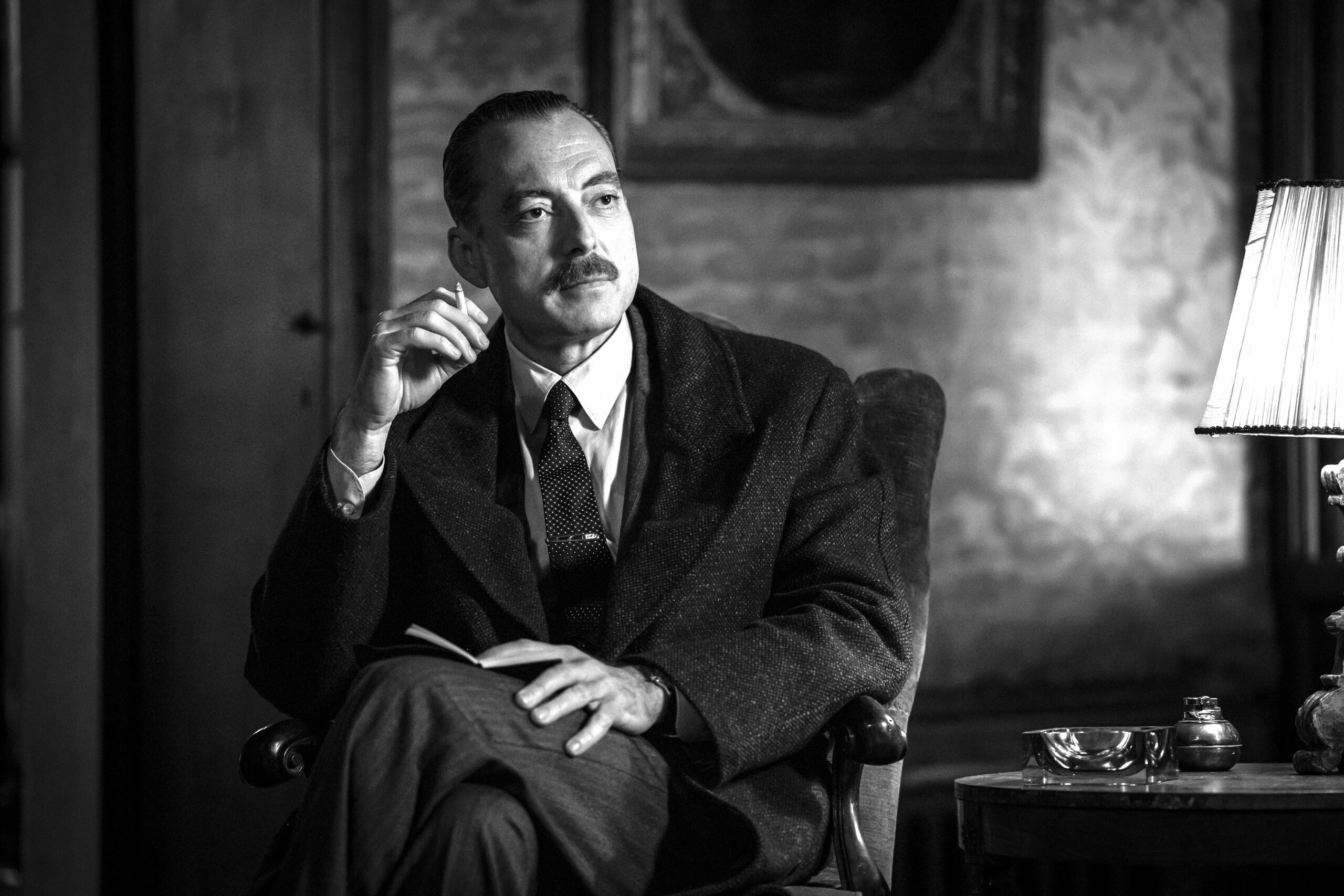

Throughout, Di Renzo parades a whole cast of historical characters through his narrative. Vincenzo Bellini appears, as does Giuseppe Verdi. Verdi is eccentric and impetuous. Zita travels between Palermo and Naples, where the two composers stage their operas. At the center of the narrative is the nineteenth century Italian poet, Giacomo Leopardi, whom the Marchesa sponsors with a monthly stipend. He spars with the spiteful and aggressive Marchesa. He writes romantic poetry, filled with love and hope. He tries to tell her that the Greeks left Sicily with “glorious ruins,” inspiring sites to be admired. But the Marchesa responds to him, “Ruins are not glorious. . . only burdensome. Particularly when they are not yours.

They are only morbid.” They only remind her, and by extension, all Sicilians, of their inglorious past, of centuries of invasion and subjugation. If there is any glory for Sicily, it is in the distant past. Garibaldi is only the most recent manifestation of Sicily’s sorrowful history. In the end, the independently-minded Marchesa calls the poet a fraud, tells him that he espouses belief and hope in his poetry while actually harboring doubt and despair in his personal life. He holds steadfastly to the fiction he creates in his poetry.

But the Marchesa calls him out and tells him that truth is preferable to his imagination. It is better to live without hope than to live a lie. In anger, the brash Marchesa renounces him as a fraud and withdraws her stipend.

In the end, on the verge of bankruptcy, the Marchesa accepts a deal with a British wine producer who wishes to use the family crest to market his wine. The income would save her villa. But he hoodwinks her: her crest is not used on a fine port but a cheap vinegar. When she discovers this, her anger overflows, and the law suit that she initiates against the company all but ruins her. This final moment in the novel serves as yet another metaphor for the exploitation of Sicilian society. This time it is the invasion of capital, where only the profit motive counts, not integrity or tradition.

Throughout, Di Renzo’s historical narrative overflows with Sicilian aphorism and references to Sicilian folklore. These are the codes and narratives by which Sicilians have conducted their lives for generations.

They are the historic aphorisms, warning signs, that have allowed Sicilians to negotiate the treacherous shoals that Fate has strewn in their way. The Hollywood film crew that begins the novel ends it. They are there in the Capuchin catacomb to make an historical drama, to exploit the Sicilians, as the wine merchant exploited the Marchesa’s heritage and compromised her integrity.

Di Renzo writes at a breathtaking pace. This historical references and personages that tumble out of every sentence all but overwhelm the reader. As his afterword demonstrates, he prepared well for his novel, and it pays off in his convincing portrait of one of the most important eras in Italy’s past. The past is never really past in Italy and in Sicily in particular. Di Renzo brings that history to life in characters, both historical and fictional, who are as convincing as they are interesting.

Ken Scambray’s most recent works are The North American Italian Renaissance: Italian Writing in America and Canada , Surface Roots: Stories, and Queen Calafia’s Paradise: California and the Italian American Novel . His essays on the Watts Towers and the Underground Gardens appear in Italian Folk: Vernacular Culture in Italian-American Lives, ed. by Joseph Sciorra and Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts: Arts, Migrations, Development ed. by Luisa Del Giudice