Dear readers,

A saint he ain’t but a reader wanted to know if I had any information on a saint with a Rossi surname who had been canonized in the late 1800s. I checked an old edition of Butler’s Lives of the Saints and I found a St. John Baptist Rossi (1698-1764) born in Voltaggio, near Genoa. His parents had four children, but from the age of ten, he was educated by a Genoese nobleman and his wife. Through the efforts of Capuchin relatives, he was invited to Rome and entered the Roman College at the age of only 13. He studied too hard and suffered a breakdown due to epilepsy. He recovered well and was ordained in 1721. He loved to visit hospitals and a night refuge for the destitute founded by Pope Celestine III. Here, he worked for forty years. He also frequently visited the hospital of Trinità dei Pellegrini. For some years, he was too diffident to hear confessions but discovered his gift for direction after a convalescence. In 1731, he became assistant priest at St. Mary in Cosmedin. Penitents of all classes flocked to his confessional to such an extent that he was dispensed from saying the divine office. He succeeded his cousin as a canon but devolved his salary to charity and to providing an organ and organist to his church. He himself lived in an attic, in extreme poverty.

***

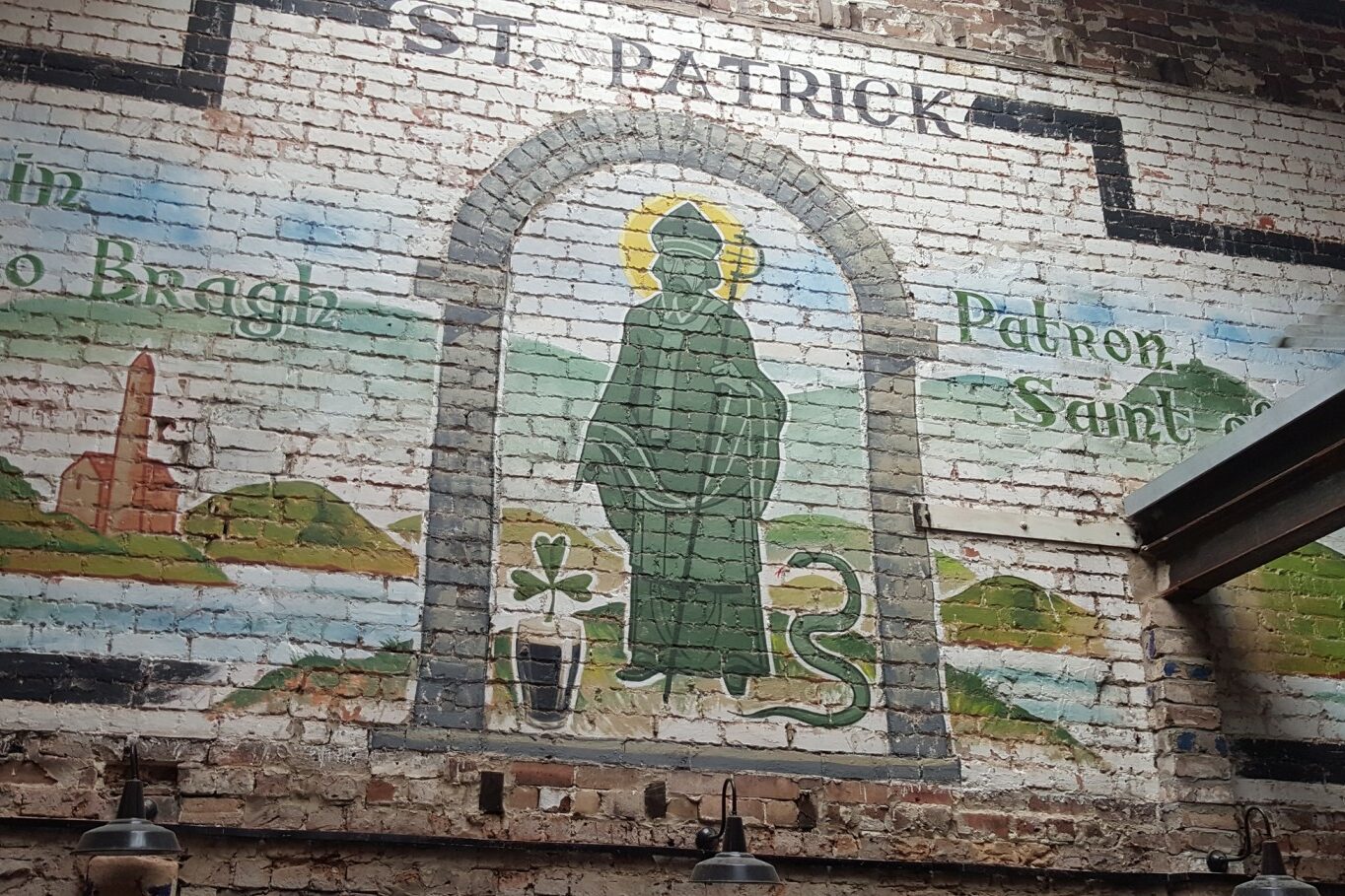

My father Vincenzo loved the Saints and looked forward to the town’s Patron Saint’s Feast. In the small towns and villages where our grandparents were born, these were the happiest days of the year. Usually, a statue of the Saint was placed on a decorated cart or wooden platform carried on the shoulders of six or eight strong men in a religious procession. These occasions were like the greatest show on Earth and the 4th of July rolled into one for children and grown-ups alike. When they came to America the feste, especially religious ones dedicated to hometown Patron Saints, were the first bit of “home away from home” the immigrants celebrated in the streets of their Italian neighborhoods. They would gaily decorate them with strips of multicolored lights, banners, and artistically arranged displays of flowers and candles, in an attempt to replicate their old villages’ feasts.

Statues of the revered Saints and Madonnas would be drawn along the streets, lined with buntings on the brawny shoulders of paesani dressed in their Sunday best: their coats, shirts, and hats would be heavy with religious medals, badges, buttons, or adorned with red, white and green sashes with foiled tinsel lettering.

The men of the comitato would be followed by their pious wives, mothers, children, and grandchildren, often chanting prayers and wearing black dresses. The most generous and active members of the religious celebration’s comitato were often men who were Sunday mass no-shows, with a passionate devotion to their paese’s Patron Saint that lasted a lifetime and was often passed on to their American-born children, who loved Saints, too, because they always meant a festa.

***

Overcoming financial problems, assisting loved ones in times of war or other dangerous situations, helping cure the ill, or petitions for a healthy child when a member of the family was pregnant meant St. Joseph’s Altars in gratitude for favors received. Often these “sacred obligations” involved more than the single petitioner but extended to his or her entire family and, often, their friends. Among the baked goods you could often find cuccidate (fig cookies), zeppole (puffed pastries filled with cream), and breads sometimes glazed with egg white and molded into traditional symbolic shapes like St.Joseph’s cane, baskets, stars, sandals, and crosses. They often included a bowl of dried fava beans, which are considered to be lucky, and carrying one in your pocket is supposed to offer protection against being penniless. Hard-boiled eggs, sardines, and fish were usually served because when the feast fell during Lent, you couldn’t eat meat. I knew that pasta con le sarde with breadcrumb topping was a traditional St. Joseph’s Day dish, but only recently I have learned that breadcrumbs represented the sawdust from St.Joseph’s carpentry business.

Mudriga or Mudrica (breadcrumb for pasta con le sarde)

Grate stale bread and sift to remove large crumbs. Heat an iron skillet on a very low flame; add bread crumbs and cook until they are golden brown. Stir constantly so crumbs do not burn. After crumbs are browned, remove from fire, add sugar according to taste, and sprinkle atop pasta con le sarde. There are many versions of this dish, and recipes for its breadcrumb may vary slightly. But rest assured a good plate of pasta con le sarde will always be topped with a hefty spoonful of it!

Cari lettori,

Non un santo, ma un lettore voleva sapere se avevo informazioni su un santo di cognome Rossi che era stato canonizzato alla fine del 1800. Ho controllato una vecchia edizione delle Vite dei Santi di Butler e ho trovato San Giovanni Battista Rossi (1698-1764) nato a Voltaggio, vicino a Genova. I suoi genitori ebbero quattro figli, ma dall’età di dieci anni fu educato da un nobile genovese e da sua moglie. Grazie agli sforzi dei parenti cappuccini, fu invitato a Roma ed entrò nel Collegio Romano a soli 13 anni. Studiando troppo intensamente, ebbe un esaurimento nervoso dovuto all’epilessia. Si riprese bene e fu ordinato nel 1721. Amava visitare gli ospedali e un rifugio notturno per indigenti fondato da Papa Celestino III. Qui lavorò per quarant’anni. Visitò spesso anche l’ospedale di Trinità dei Pellegrini. Per alcuni anni fu troppo diffidente per ascoltare le confessioni, ma dopo una convalescenza scoprì il suo dono come guida spirituale. Nel 1731 divenne viceparroco a Santa Maria in Cosmedin. I penitenti di tutte le classi accorrevano al suo confessionale a tal punto che venne dispensato dal recitare l’ufficio divino. Succedette al cugino come canonico, ma donò il suo stipendio alla carità e alla fornitura di un organo e di un organista alla sua chiesa. Visse in una soffitta, in estrema povertà.

***

Mio padre Vincenzo amava i santi e aspettava con ansia la festa del Patrono del paese. Nelle piccole città e nei villaggi dove sono nati i nostri nonni, questi erano i giorni più felici dell’anno. Di solito, la statua del Santo veniva posta su un carro decorato o su una piattaforma di legno portata a spalla da sei o otto uomini robusti in una processione religiosa. Queste occasioni erano come il più grande spettacolo del mondo e il 4 luglio riuniti in un’unica festa per bambini e adulti. Quando arrivarono in America, le feste, soprattutto quelle religiose dedicate ai Santi patroni, furono il primo pezzo di “casa lontano da casa” che gli immigrati celebravano nelle strade dei loro quartieri italiani. Le decoravano allegramente con strisce di luci multicolori, striscioni e allestimenti artistici di fiori e candele, nel tentativo di replicare le feste dei loro vecchi villaggi.

Le statue dei Santi e delle Madonne più venerati venivano disegnate lungo le strade, allineate con i festoni sulle spalle robuste dei paesani vestiti con il loro abito domenicale: i loro cappotti, camicie e cappelli erano appesantiti da medaglie religiose, distintivi, bottoni, o adornati con fasce rosse, bianche e verdi con scritte in orpelli smerigliati.

Gli uomini del comitato erano seguiti dalle loro pie mogli, madri, figli e nipoti, spesso intonando preghiere e indossando abiti neri. I membri più generosi e attivi del comitato della festa religiosa erano spesso uomini che non si presentavano alla messa domenicale, con una devozione appassionata per il Santo Patrono del loro Paese che durava da una vita e che spesso veniva trasmessa ai loro figli nati in America, che amavano anche loro i Santi perché significavano sempre una festa.

***

Superare problemi finanziari, assistere i propri cari in tempo di guerra o in altre situazioni di pericolo, aiutare a curare i malati o chiedere un figlio sano quando un membro della famiglia era incinta significava recarsi poi agli altari di San Giuseppe per ringraziare dei favori ricevuti. Spesso questi “obblighi sacri” non riguardavano solo il singolo richiedente, ma si estendevano a tutta la sua famiglia e, spesso, i suoi amici. Tra i prodotti da forno si potevano trovare spesso cuccidate (biscotti ai fichi), zeppole (paste sfogliate ripiene di crema) e pani talvolta glassati con albume d’uovo e modellati in forme simboliche tradizionali come il bastone di San Giuseppe, cesti, stelle, sandali e croci. Spesso includevano una ciotola di fave secche, considerate fortunate, e portarne una in tasca si suppone che offra protezione contro la mancanza di denaro. Di solito venivano servite uova sode, sardine e pesce, perché quando la festa cadeva in Quaresima non si poteva mangiare carne. Sapevo che la pasta con le sarde con la mollica di pane era un piatto tradizionale del giorno di San Giuseppe, ma solo di recente ho appreso che la mollica di pane rappresentava la segatura dell’attività da falegname di San Giuseppe.

Mudriga o Mudrica (mollica di pane per la pasta con le sarde)

Grattugiare il pane raffermo e setacciarlo per eliminare le briciole più grandi. Scaldare una padella di ferro a fuoco molto basso; aggiungere la mollica di pane e cuocere fino a quando non sarà dorata. Mescolare continuamente per evitare che le briciole si brucino. Quando le briciole saranno dorate, toglietele dal fuoco e cospargetele sulla pasta con le sarde. Esistono molte versioni di questo piatto e le ricette per la sua panatura possono variare leggermente. Ma state certi che un buon piatto di pasta con le sarde sarà sempre condito con una bella cucchiaiata!