Ever since the Burger King opened on Via Nazionale, teenagers have come to Piazza Pasquino to eat French fries and to place paper crowns on my head. These coronations never last long. A stray breeze or a conscientious tour guide always intervenes and deposes me. During my brief reign, however, I think of Umberto II, the last King of Italy, who ruled for just over a month. Romans still call him il Re di Maggio, the May King.

Umberto was the only son of Vittorio Emanuele III, nicknamed Sciaboletta (Little Sabre) because he was barely five feet tall. Even if he had been a physical giant, however, he would have remained a moral pygmy because of his collusion with the Fascist regime. Determined to repair the House of Savoy’s image after the fall of Benito Mussolini, the king had transferred power to his son while retaining his title. But on May 9, 1946, he abdicated his throne to Umberto, a desperate last stand against a referendum to abolish the monarchy.

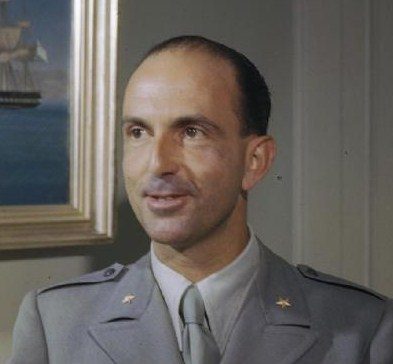

Umberto faced a hostile press. The newspapers had never forgiven the royal family for abandoning Rome in ‘43. “Bad kings make good subjects,” editors reminded their staff. Cartoonists exploited Umberto’s physical quirks. Tall, stiff, and balding, he had smooth, clean-shaven blue cheeks, thin lips, and a weak chin. Dressed in military uniform, decorated with the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, he seemed more like a majordomo than a major-general.

Columnists capitalized on his peccadillos. Like great-grandfather Vittorio Emanuele II, Umberto in his youth had been louche. Queen Margherita, his nonna, had called him “a rascal, a true Savoy.” After crashing the Marchesa Bertarelli’s party, the Crown Prince—before the terrified eyes of four liveried houseboys—launched from the window all the desserts from the buffet table. He capped the evening by unloading a cow from a delivery truck and leading it up the carpeted staircase.

Umberto’s libido was as strong as his piety. In the words of a family chronicler, he was “forever rushing between chapel and brothel, confessional and steam bath.” He courted Hollywood star Jeanette McDonald on the Côte d’Azur, wearing a Monty uniform and warbling “Indian Love Call,” and encouraged the advances of Mexican spitfire Dolores del Río. The prince also had affairs with army officers, who received U-shaped jewels and diamond-studded fleurs-de-lis. One conquest flaunted a silver cigarette lighter inscribed with the words “Dimmi di sì!” (Say yes to me!)

When Mussolini assembled a file on these indiscretions, Umberto married Princess Maria José of Belgium. The prince even designed her wedding dress. Gossips claimed that he had modeled it himself. Umberto doted on Maria José but resumed his philandering. When the royal couple began to sleep apart, however, he yearned to rekindle their love. He disguised himself as a hussar and snuck into her bedroom. The princess shrieked for the palace guards. Three of their four children, a gynecologist later confirmed, were conceived through artificial insemination.

These scandals, bookies predicted, would doom the monarchy. As the referendum approached, however, Umberto won supporters. Southerners adored him. The young king had served with distinction at Battle of Cassino and had tended the wounded. He could name every Sicilian village between Messina and Palermo, could describe every tower, fountain, and citrus grove. When the king won 47% of the national vote, reactionaries advised him to stage a coup. If he rejected the plebiscite and withdrew to Naples, the army would support him in the ensuing civil war. “My house united Italy,” Umberto said. “I will not divide it.”

At 3:00 p.m. on June 13, 1946, the king vacated the Quirinal. In the courtyard he passed in review of the palace coachmen. He wore a gray flannel suit and carried a fedora and a walking stick. The servants and gentlemen-in-waiting sobbed. Pale and drawn, Umberto looked much older than his forty-one years, but his head was held high, and now and then he managed a smile. At Ciampino Airport, as he stepped inside the plane that was to carry him to Portugal, a carabiniere squeezed his hand and said, “Your Majesty, we will never forget you!”

No official, however, attended Umberto’s 1983 funeral in Geneva. Since then, his son (Vittorio Emanuele IV) has demanded that Italy pay 260 million Euros “to compensate for emotional damages suffered in exile.” His grandson (Emanuele Filiberto) appears on Ballando con le stelle, the Italian version of Dancing with the Stars. Now the property of curators and academicians, the throne of Italy stands in an old museum in Turin.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.