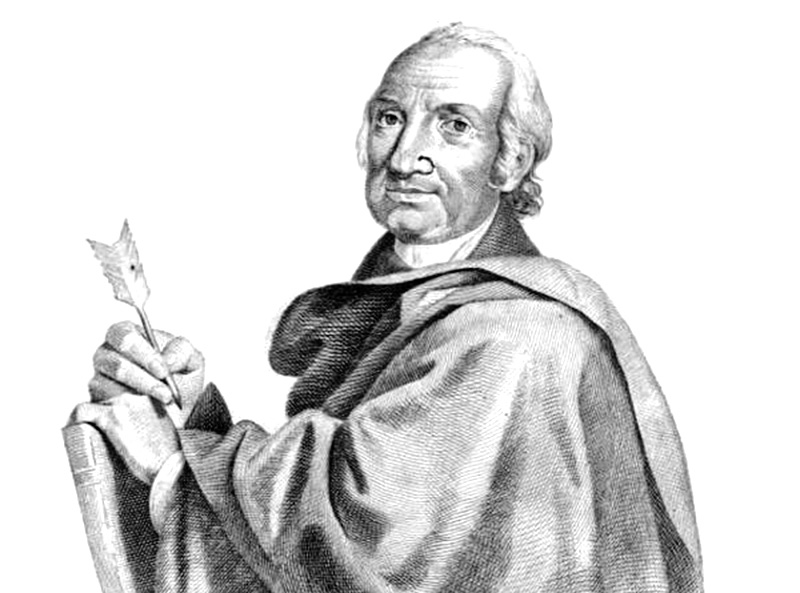

2015 marks the 200th anniversary of the death of Giovanni Meli, Sicily’s most celebrated poet, who died of pneumonia on December 20, 1815. Prof. Giovanni Ruffino, director of the Centro di Studi Filologici e Linguistici Siciliani, in collaboration with Sicily’s three major universities organized a four-day conference in Palermo and in Cinisi on December 4-7, 2015. Scholars from around the world will discuss Meli’s multifaceted talents and his contribution to the Sicilian language and to its literature; Nuova Ipsa Editore, a publisher from Palermo, has embarked on a most ambitious project that will publish eleven volumes of his impressive opus. Prof. Salvo Zarcone of the University of Palermo has been given the task of directing the efforts of many scholars to edit and re-evaluate Meli’s works from a modern perspective. They have already published two volumes, La Buccolica and Favuli morali, as well as a large size edition of the Don Chisciotti e Sanciu Panza.

The writer of this article has been commissioned to edit the three volumes containing his Lirica (Lyrical Poems). While these volumes are in Sicilian and Italian, the English-speaking world has not been ignored. The present writer, who had already translated the Don Chisciotti and Sanciu Panza, Moral Fables, The Origin of the World and numerous other poems, did not let this occasion pass by without honoring the memory of the poet. He recently published The Poetry of Giovanni Meli, a monumental bilingual anthology. All of these activities pay homage to a poet who was known as “the Perfect Sicilian Poet” and who embodied the essence of “Sicelitude” in his life and in his work.

Giovanni Meli (1740-1815) was not a minor literary figure. According to Mario Apollonio, he wrote some of the “loftiest and purest poetry in 18th century Europe.” Had he written in Italian he would have been regarded as one of the major poets of his century. Giacomo Leopardi in his Zibaldone identified two dialect writers who would last the test of time: Carlo Goldoni and Giovanni Meli. Time has been more kind to Goldoni than to Meli. But in his lifetime, Meli was extremely popular and enjoyed wide recognition even outside of Italy. He had contacts with the major writers of Europe and was much admired by the likes of W. Goethe, J. Herder, and many others. Goethe himself actually translated the first eight lines of one of Meli’s most celebrated odes: “L’occhi” (The Eyes).

Meli was in fact the most translated Italian poet of his time. His works were translated into French, German, English, and even into several Italian dialects such as Venetian. Fifty years ago one could occasionally hear someone recite the fable of the “Surci”: “un surciteddu di testa sbintata/avia pigghiatu la via di l’acitu…” (A little mouse who was light-headed, brash / had gone the way of wine to vinegar…). His “Ditirammu Sarudda,” a lively and explosive poem in praise of wine, was often recited at weddings. Yet today few people know who he is even in Sicily. In this country, the present writer has devoted much of his academic career to make the case that this poet speaks to the world and not just to Sicilians. His Moral Fables, a collection of 90 fables in which animals interact with one another in a most natural way, are witty and wise. Unlike other fable writers who often engage in lengthy and boring moral lessons, Meli never lectures. The message emerges from the animals’ dialogue, as happens in the fable of the father crab who was trying to teach his offspring how to walk “straight” but refused to provide the model. The oldest crablet said to the father:

“As maker you’re the one

Who ought to teach us, Dad!

So show us how to walk.

There is no need to talk.”

“You insolent upstart!

You certainly have nerve!

As model I should serve?

I’m freer than the breeze,

I do not have to please.

And if you dare, you lice,

To answer one more time…”

He kept up his advice

And they their pantomime.

Wrong father, crooked young

Till death will come along.

Critics regard Moral Fables as his most congenial work because he could manifest his real feelings through the animals’ voices without worrying about censorship. He certainly was not sparing in his criticism of society, although he was never harsh. He chastised greed and intolerance, exploitation of the poor, the laziness of the nobility, the lack of justice and fairness in the world, but as Vincenzo De Maria said : “La sua penna è come un fioretto che penetra di punta e par che neppure s’avverta per la sottigliezza della lama.” (His pen is like a foil that pierces with its tip and owing to the thinness of the blade is barely felt.) Still the heart of a giant can be pierced just as easily with a thin blade as with a dagger.

Equally famous are his Odes. Meli was a physician by profession and had access to the Palermo nobility. The ladies vied to have him at their elegant parties. The Odes in which he celebrated the beauties of these aristocratic women display great virtuosity. They are erotic without being offensive, they contain a restrained sensuality that titillates and tickles, but is never obscene. He often uses double entendre, hinting, suggesting, and teasing. His light touch creates an atmosphere of rarefied eroticism which barely masks the object of his desire.

Meli portrayed himself as “l’amicu di la paci e la quieti,” (the friend of peace and tranquility), but he had a much more complex personality. Throughout his life he always sought to live a tranquil life in the bosom of nature. The theme of the Golden Age was ever present in his mind as we can see from the poems of his Buccolica. They are a celebration of the love that governs the universe and express his yearning for the simpler life with equality and justice for the shepherds and farmers who are the producers of all wealth. But Meli was also a realist, a pragmatist, a scientist who knew first hand how difficult it was to change the status quo.

This man, who believed only what he could touch with his own hands was also a dreamer, an idealist, who yearned to see justice in the world. He was a mason and was animated by a spirit of reform. These two tendencies in him were embodied in the two characters of his Don Chisciotti and Sanciu Panza, a long mock epic poem. This work was not an imitation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. It was a rethinking of the couple from a Sicilian point of view in which the hero turns out to be Sanciu, not Don Chisciotti, who was described by Sanciu as “un omu chi nun sapia cunzari na ‘nzalata e pritinnia di cunzari lu munnu.” (A man who did not know how to fix a salad and yet pretended he could fix the world). Meli’s deliriums were projected onto the character of Don Chisciotti. Sanciu instead represented Meli’s down to earth, pessimistic views about society. He started out as a tabula rasa, an ignorant peasant, but the lessons of life and his suffering taught him to become a natural philosopher. The tension between these two poles was a metaphor for the poet’s divided self. The fact that Sanciu was the hero of the poem underscored the poet’s own skepticism about the stagnant Sicilian society of his time. The world, in the end, proved to be unredeemable.

Meli wrote in Sicilian, not Italian, and he considered himself the heir to Theocritus, the poet from Siracusa who is considered the father of Bucolic poetry. In his endeavor to create an illustrious Sicilian language he was following a long tradition that had begun with the Emperor Frederick II of Hoenstaufen. The poets of his “Sicilian School,” one of whom (Giacomo da Lentini) had invented the sonnet, created a new language that flourished throughout Italy and provided the bases for the literary language of the country, as Dante readily conceded in his De Vulgari Eloquentia when he said that “the first hundred fifty years of Italian poetry were written in Sicilian”.

The conference in Palermo this December will undoubtedly make the point that Meli was indeed a poet for the ages. His wisdom, his wit, his sly humor and deliciously malicious smile can still delight any audience that is willing to stop running for a moment to listen to him.