January is my favorite month in Rome. Consecrated to the god of beginnings, it is the best time to recapture the magic those British lords on the Grand Tour must have felt, when they arrived from the grey north to this golden palimpsest of travertine and snow. Winter in London was never like this!

Rome’s January thaw, a season unto itself, sharpens the city’s dulled edges and revives its faded colors. The sky, a grey rag for six weeks, becomes a turquoise canopy of state. The sun, once veiled by the mists of November and the frosts of December, now shines like a burnished armillary sphere in a Baroque library.

The chill heightens the senses in Rome’s historic center. In the Borgo district, spectators trace the patterns of streaming breath from the ice skaters below Castel Sant’Angelo. In the Prati, residents savor the tinkling wind chimes from rooftop gardens. Here in Parione, pedestrians read the menus of local restaurants with their nostrils.

Saffron permeates Piazza Pasquino. Francesco, the new chef at Cul de Sac, is Abruzzese. A graduate of the Culinary School of Villa Santa Maria in the Province of Chieti, he grew up on the Navelli Plain near L’Aquila, where the muddy soil is darker than chocolate. For millennia, this area has supplied Rome with the best saffron in Italy.

Made from the dried stigmas of the crocus, saffron is the world’s most expensive spice. Because its production is so labor intensive, it is worth more than its weight in gold. No machine can harvest those fiddly purple flowers. The work must be done by hand. The delicate red threads are separated from the petals, teased and plucked, and dried over a wood fire until they are steamy and sweet.

It takes 100,000 crocuses (and 500 hours of labor) to yield one kilo of saffron. Happily, saffron is potent. A little goes a long way. A single gram is enough to spice and color twelve portions of golden risotto milanese.

Francesco, however, prepares Abruzzese delicacies: fresh ricotta with honey and saffron; braised fennel with figs and saffron; trofie with zucchini flowers, pancetta, and saffron; prawns and squid in saffron sauce. The intoxicating smell revives imperial memories.

Saffron was a status symbol in ancient Rome. Patricians and wealthy plebeians used it as perfume and make-up. They glazed their wedding cakes with saffron. They dyed their robes in saffron. They flavored their drinks and scented their hair. They also stocked their medicine cabinets. Saffron rejuvenated the skin, restored the liver, relieved coughs and hiccups, and refreshed bloodshot eyes. It cured hangovers but not, alas, megalomania.

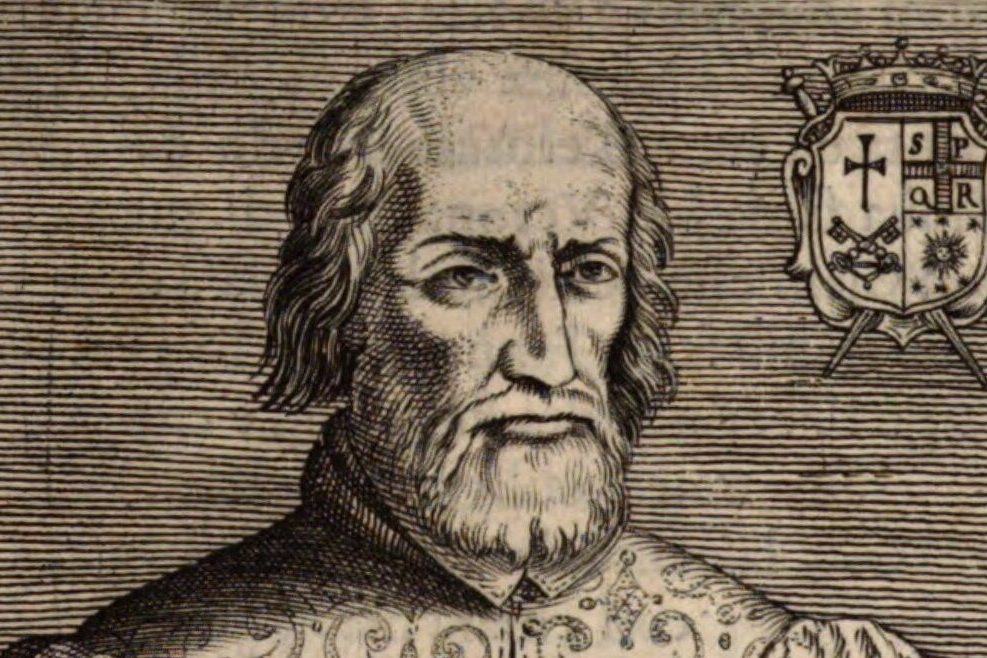

The Emperor Heliogabalus—to prove he was an incarnation of the Syrian sun god—bathed in saffron until his skin turned gold. This blasphemy doomed him to assassination, for saffron was sacred. During religious ceremonies, Romans burned it as an offering in braziers and censed their temple altars and statues with it. Saffron purified public halls, baths, and theaters and was spread along parade routes to bless generals and magistrates. It also inaugurated the New Year.

January celebrated the election of Rome’s consuls, its two chief magistrates, and honored the Capitol Lares and Penates, guardian spirits of the national hearth and pantry. Between the Kalends and the Ides of the month, saffron spiced the air, enticing Janus, the two-headed janitor of the gods, to unlock the city’s shining temples.

Peace and goodwill ruled. Lawyers withdrew suits from the courts. Politicians refrained from disputes in the Forum. Tradesmen stopped cursing on the Aventine. A golden, rosy glow suffused the Seven Hills and reconciled the bitterest enemies. The very air shined with scented flames as saffron crackled on the public hearths. As the red firelight struck the gilded temples, the flickering radiance reflected over the rooftops.

Clad in spotless white, a procession ascends the Capitol’s peak. Quaestors and aediles, praetors and censors observe the Rex Sacrorum, the High Priest of the Senate, perform the rites of Janus. The consuls-elect, dressed in saffron togas, sit on their chairs of office. Unbroken bulls offer their throats to be slit, bulls fattened on Falerian fields.

Saffron incense rises to heaven. From Olympus, Jupiter surveys the Mediterranean. Everything on this porcelain platter belongs to Rome, but its purpled glory will disappear like last spring’s crocuses

At Cul de Sac, waiters emerge from the kitchen with a steaming tureen and serve diners. What do Romans see when they stare into a bowl of lemon and saffron risotto? The lost gold of empire, the snapped threads of fate.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.