Located on the west bank of the Tiber, south of Vatican City, Trastevere is a world apart. For centuries, this district was disconnected from central Rome, geographically and administratively. Low taxes and light regulation attracted Italians from farflung regions. Most of Rome’s Jews lived here, before the Ghetto was created across the river in 1526. Local fishermen and sailors based at Ostia also made the neighborhood their home.

Until recently, the countryside penetrated Trastevere. Vineyards, orchards, gardens, and chicken coops abounded, and artichokes and zucchini grew in the hidden courtyards. From a maze of narrow streets and weathered cobblestones, rises the Janiculum. When the breeze blows from the southeast, pine and myrtle scent the air.

Partial isolation and a unique subculture give this working-class enclave a bohemian atmosphere. College students string lingerie across the alleys. Widows smoke Nazionali cigarettes and water geraniums on rusted balconies. Fortune tellers in Piazza Santa Maria use trained parakeets to predict the future. Accordionists play mazurkas in cafés.

“Romans are one thing,” residents say. “Trasteverini are another.” Every July, they hold a block party called the Festival of Noantri (Us Guys). Its origins reveal much about the neighborhood’s character.

On July 16, 1535, the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, a torrential storm nearly drowned some fishermen on the Tiber. Pulling to shore, they found a wooden statue of the Madonna near the mouth of the river. The grateful fishermen donated the statue to the Carmelite friars at the Church of San Crisgono in Piazza Sonnino, who called her la Madonna Fiumarola (the Madonna of the River).

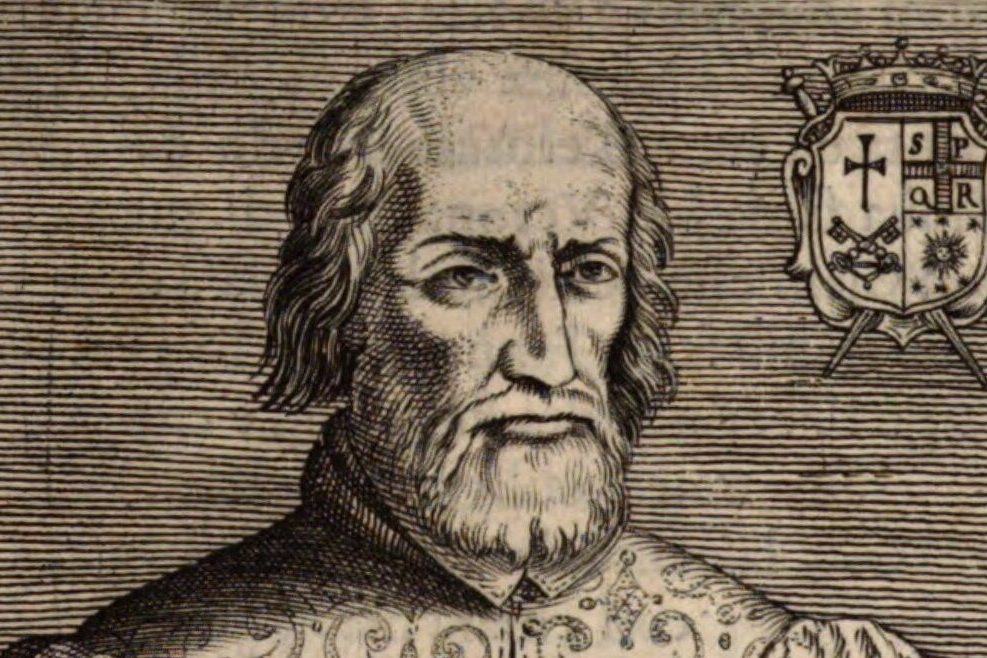

A generation later, Pope Gregory XIII transferred the statue to the Church of Sant’Agata in Lago San Giovanni de Matha. This outrage occurred on the anniversary of the statue’s discovery. Best known for reforming the calendar, Gregory had notoriously bad timing. After the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, he celebrated a Te Deum mass in Rome. Under a cloak of piety, the faithful created a religious festival to subvert the Vatican.

Each year, the Madonna Fiumarola returns to her original home. Bejeweled and elaborately dressed, she is carried from Sant’Agata back to San Crisgono, where she stays for eight days before returning by boat along the river. Cheers greet the fireworks from the Aventine’s Giardino degli Aranci. Scattering over the Tiber and drifting passed the Ponte Garibaldi, sparks illuminate the statue of Trastevere’s other patron saint.

Giuseppe Gioachino Belli was born on Via dei Redentoristi on September 7, 1791, on the eve of the French Revolution. He died on December 21, 1863, seven years before the House of Savoy defeated the Papal States. Liberal friends teased that he had wasted his life in a reactionary backwater during a century of progress. Belli retorted that it was a miracle he had survived at all.

Dysentery nearly killed him in infancy. His father died of cholera or typhus shortly after taking a clerkship in Civitavecchia. Moving back to Rome, the family was forced to take cheap lodgings in Via del Corso.

After drudging as a copyist, Belli married a wealthy widow from the noble Conti family. The couple settled in Palazzo Poli, beside the Fountain of Trevi. Leisure allowed Belli to write poetry, but his health was poor. He suffered from stomach cramps and bad nerves. When his wife suddenly died, he sold the furniture to pay their debts.

An accountant and later a censor in the Vatican bureaucracy, Belli belonged to a small but harried middle class, squeezed between an ecclesiastical elite and the masses. He was anything but a man of the people, but in a wild burst of creativity during the 1820s and 30s he wrote some 2,300 sonnets in Romanesco, Rome’s rough-and-ready street language of lopped syllables and stuffed consonants. Nearly every day, he would visit me in Piazza Pasquino and recite his latest poem on gourmandizing pontiffs or masturbating penitents.

Time and routine turned this sly man-about-town, so handsome in cape and cravat, into a pince-nezed civil servant with plastered hair and wispy mutton-chop sideburns. The Revolution of 1848 appalled him.

After Pius IX fled Rome, he repudiated politics. On his deathbed, he begged his confessor to burn his work. Now he stands in Piazza Belli, immortalized in white travertine, wearing a beaver hat and holding a knobbed cane.

Respectability is the kiss of death. Belli is now a monument, and Yuppies have gentrified Piazza S. Cecilia. But as long Romans say bbuono instead of buono and prepare pollo alla papalina for Sunday dinner, Trastevere will live in our hearts and on our tongues.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.