Even statues need sleep. The lucky ones recline on their pediments and snooze in the sun. The rest of us are carthorses, napping on our feet in the wee hours. Thus refreshed, we can better shoulder the burden of time. Sleep is impossible, however, during the Notti Bianche, Rome’s garish White Nights.

Each September, this festival draws two to three million visitors. For twenty-four hours, the city’s churches, museums, and galleries are open to the public. Their doors and windows blaze like a foundry. Rome glows. Light bulbs decorate the frame of the Garbatella gasholder. Projectors flash slides of Sophia Loren on the Pyramid of Cestius. Floodlights transform the Vittoriano into a radioactive iceberg.

Power lines crackle and hum, but spectators ignore the stray sparks amid the strobes and disco lights in the Piazza di Spagna. The city’s overstrained power grid always threatens to short-circuit during the festival. Rome’s first White Night, in fact, coincided with Italy’s worst blackout since World War Two.

Goaded by the success of the first Nuit Blanche in Paris, Mayor Walter Veltroni was determined to stage a similar event on the Seven Hills. This cultural binge, to be held on Saturday, September 28, 2003, would be his “token of love” to the Eternal City. The Camera di Commercio was delighted. Such an extravaganza would promote the arts, goose tourism, and generate business.

The overcast sky at the opening ceremony worried the superstitious. “Is this an omen?” reporters asked. Veltroni laughed. A modern mayor rather than an ancient aedile, he believed in public relations, not augury. Besides, Passotti Ombrelli had supplied the VIPs with free umbrellas. The handmade leather handles were trimmed with garnets and Swarovski crystals.

The festival began well. Veltroni took his rival, Paris Mayor Bertrand Delanoe, to a performance of Romeo and Juliet in Villa Borghese. Mercutio wore glitter and mascara. Next was Lucio Dalla’s pop version of Tosca in the Campidoglio. The singers sounded as if they were auditioning for Les Miz. Drizzle dampened a midnight concert of Nicola Piovani’s greatest film hits in Piazza Navona. The two mayors, however, still dined al fresco at Tre Scalini and toasted each other for the paparazzi.

As the cameras flashed, Rome vanished. Street lamps, traffic signals, and building lights were dead. People blamed the window air conditioners in the Corviale housing projects on the city’s outskirts, which had prompted partial power cuts in June. The actual cause was a gale in Ticino. Toppled pines had snapped the Lukmanier line. The domino effect had crippled Italy’s entire grid, except for the islands of Sardinia and Elba.

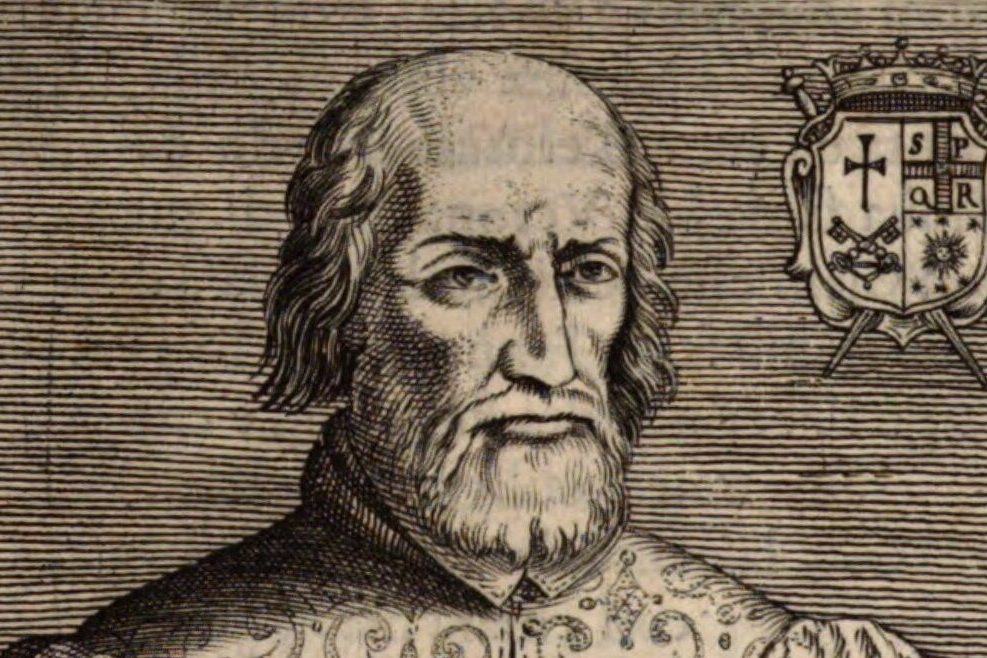

At the Apostolic Palace, the Pope joked about the Ninth Plague of Egypt. The Director of the Vatican Museums, who had prayed that the White Night would improve attendance, forced a laugh. As His Holiness struggled to light a candle with a palsied hand, the emergency generators flicked on. Fiat lux! Light also returned to some hospitals and key government ministries, but darkness ruled the rest of Rome.

The drizzle had turned to rain, the rain into a torrent. Galleries and museums that had kept their doors open were forced to shoo visitors out for security reasons. A ghostly legion of wet and bedraggled revelers was stranded on the streets. Twelve thousand found refuge in Rome’s subway stations, which had remained open all night for the festival.

The less fortunate panicked. Lost women screamed. Trapped motorists pounded horns. Shoppers brawled on Piazza Colonna. Pedestrians were trampled on Via del Babuino. A mob nearly breached the barricaded doors of the Taverna del Campo. Police abandoned the historic district, but no looting occurred. The only fatalities were three old women, who slipped and tumbled down their apartment stairs.

Rome holds spectacles of light to forget such darkness. This year, ten thousand crystal globes change colors in the Circo Massimo. Choreographed lasers form a kaleidoscope in the Foro di Cesare. Fire-eaters spew flames and dervishes twirl torches on the Gianicolo. Taillights flow like lava on the Lungotevere.

As the city burns, I think of Nero. He also promoted the arts. To provide the proper setting for his recital of the fall of Troy, he set the Palatine ablaze. Our White Nights are less destructive than his, but are they less pretentious? Few of their beauties can survive the light of day.

Dawn approaches. Dressed in saffron, Aurora tiptoes over the Alban Hills. The morning dew soothes and closes my itchy eyes. Maybe now I will get some sleep.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.