“Pasquino, my man!” booms Tyrell. Once a sound engineer for Earth, Wind, and Fire, he now lives in the Parione district and works in the Auditorium Parco della Musica. The only city with more soul than Rome, he jokes, is Detroit. Whenever he sees me, he spins on his heel, points, and sings: “Love is written in the stone!”

Everyone knows that. Ovid tells the story of Pygmalion and Galatea. Disillusioned by hard-hearted women, a flinty old sculptor carves and pines for the statue of a nubile girl. Venus pities him and brings the statue to life. The two fall into bed, and Cupid showers them with rose petals.

Roman statues treasure this tale, although no happy metamorphosis awaits us. We must stand alone until we disintegrate. Only then will our dust mingle and love. For now, we can only yearn for a sweetheart. Mine is Madama Lucrezia, who rests on a plinth in a corner of Piazza San Marco, between the Basilica of St. Mark and Palazzo Venezia.

Rome’s only female talking statue, Lucrezia rarely jokes. Blame her tragic history.

At the turn of the 15th century, workmen in Campo Marzio unearthed fragments of a female colossus near Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. They left her foot in what is now Via del Piè di Marmo for some Prince Charming to claim. Her ten-foot-high bust was set by the Pantheon, where it caught the eye of Alfonso V of Naples.

Alfonso had come to Rome in 1452 to petition Pope Callistus III for an annulment. His Highness wanted to divorce Maria of Castile and marry Lucrezia d’Alagano, an Amalfian noblewoman. The two lovers had met four years ago on St. John’s Eve.

Crossing a street to participate in the festival, Alfonso had passed Palazzo d’Alagno. Lurcrezia, then eighteen, approached with a vase of barley. Back then, Neapolitan girls try to foresee their future loves by cultivating barley on their windowsills. “I’ve sown barley thinking of Your Majesty,” she said. “Now I expect a present.”

Delighted, Alfonso ordered his treasurer to give Lucrezia a bag of gold. She took the bag and fished for an alfonso, a small coin worth a doubloon. “One Alfonso is enough for me,” she said and tripped away.

The girl brightened Alfonso’s court. She entertained ambassadors, proposed reforms in council, and inspired the poet Antonio Beccadelli. Sculptors carved her face on the Castel Nuovo’s triumphal arch. She was Naples’ true queen. Virtuous as well as beautiful, she would not sleep with Alfonso until Rome blessed their union. Shouldn’t His Holiness reward such goodness and unite crown and populace in mutual love?

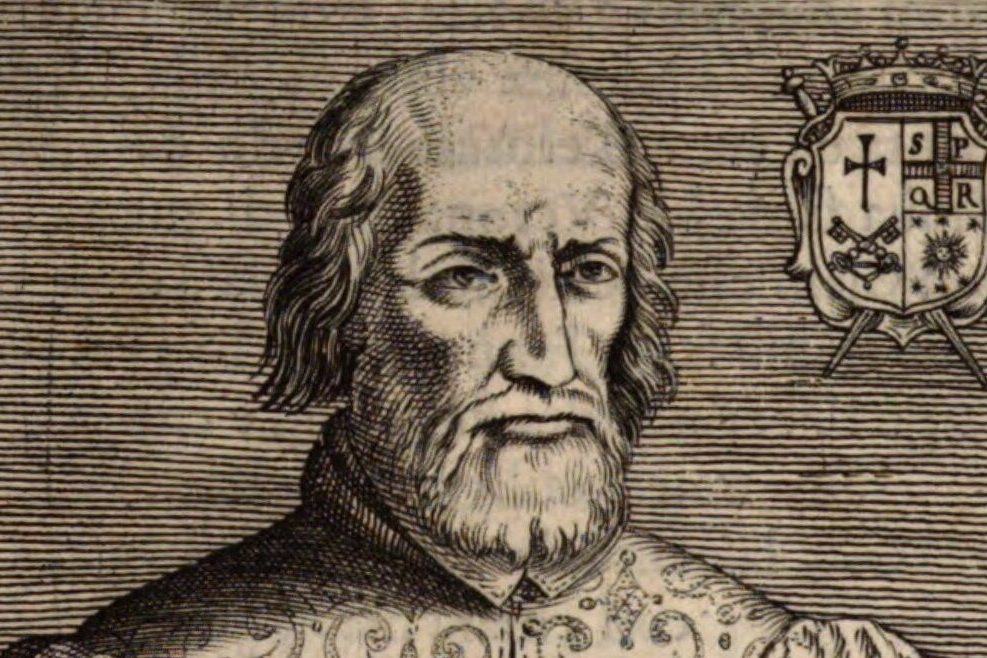

Callistus, a Borgia who considered all women horseflesh, refused. If the King chose to moon over a coy virgin, that was his business. To soften Lucrezia’s disappointment, Alfonso gave her the island of Ischia and the female colossus in Campo Marzio. She could visit it whenever she came to Rome.

The statue intrigued Lucrezia, but no one could solve its mystery. Some antiquarians claimed it represented the Empress Faustina, the wife Constantius II. Others said the statue honored Isis. After all, it had been discovered at the former site of the Iseum, the Roman temple to this foreign goddess. The statue’s gown, with its double knot secured by an amulet, resembled the robes of Egyptian priestesses.

After Alfonso died in 1458, Lucrezia fled Naples and moved to Rome. For twenty years, she wore rags and begged for scraps. Every week, she placed posies on the bust that the king had given her until heartbreak finally killed her. Cardinal Innocenzo Cibo later moved the statue to the Pigna district, where the unfortunate had endured disgrace. Locals called it Madama Lucrezia in her honor.

History is a carnival. At the Ballo dei Poveretti, cripples and hunchbacks danced before Lucrezia. Urchins decorated her with garlands of ribbon and lace and necklaces of garlic, onions, and peperoncini. During the Napoleonic wars, Jacobins toppled her and broke her nose. A wag placed this lampoon on her back: “I can’t stand it anymore!”

Isis, they say, retrieved and restored the scattered pieces of her husband Osiris’s body. I wish I could do the same for Lucrezia, but my suit is hopeless. She has eyes only for Marforio, who once reclined in the same piazza before being ensconced in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori. Who can blame her? He is a river god: sleek and smarmy as a dolce vita lounge lizard.

Tyrell can’t hear my sighs. Listening to his iPod, he sings: “Love is written in the stone!”

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.