Wedged between the Regola and Parione districts, Campo de’ Fiori features Rome’s most spectacular flower market. Wassily Kandinsky, the Russian painter whose name adorns an apartment house on nearby Via di San Salvatore, called it “a symphony of color.” Each season strikes a different keynote: chrysanthemums in fall, poinsettias in winter, lilies in spring, roses in summer.

Campo de’ Fiori literally means Field of Flowers. At least twice in the past twenty-two centuries, this market has been a meadow. Even now, it feels like a country fair in the middle of the city. Romans enjoy this bucolic retreat but never let its fragrance cloud their judgment. The piazza’s notorious history complicates its beauty. Blood, not manure, has made its roses bloom.

Until the Late Republic, the district between the Tiber and the Temple of Venus remained underdeveloped due to frequent flooding. Fortunately, politicians always pursue public works to buy votes. When Pompey the Great built a sports complex in the Lago di Torre Argentina, he converted the scrub and muck into a proper lot for spectators and vendors.

Pompey called the site Campus Floralis after Flora Primavera, the Roman goddess of spring and flowers. That, at least, is what Victorian classicists claimed. More likely, Pompey was honoring Flora Meretrix, Rome’s greatest courtesan, who never allowed Pompey to leave her bed without showering him with petals and biting his ear.

Until the Vandals sacked Rome, florists and butchers, prostitutes and loan sharks plied their trade in this open-air market. After the city fell, the fairgrounds reverted to a field. Borage and yarrow ran amok. For a thousand years, the poor planted vegetable and flower gardens but fought a losing battle with hares and badgers.

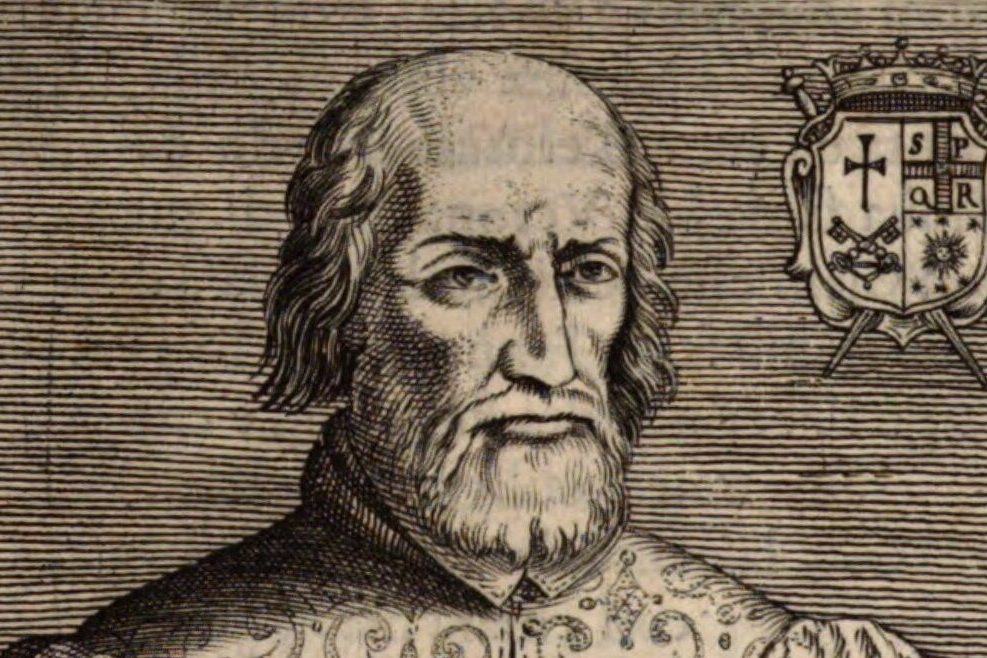

Then, in the mid-1400s, Pope Callistus III reorganized and paved the entire district. During this renovation, many elegant buildings were constructed, such as the Palazzo Orsini and the Palazzo della Cancelleria. Once the area was restored, cardinals and ambassadors socialized here. The rich established a thriving horse market, held every Monday and Saturday. Hotels and inns, taverns and restaurants, studios and workshops sprung up overnight.

As Rome’s only churchless piazza, Campo de’ Fiori was consecrated to commerce. Its surrounding streets honored various trades: Via dei Balestrari (crossbow-makers), Via dei Baullari (coffer-makers), Via dei Cappellari (hatters), Via dei Chiavari (locksmiths) and Via dei Giubbonari (tailors). Florists, however, gave the square its distinct character.

Business was brisk. Visitors bought wreaths for the jockeys in the palio, garlands for the dancers and street musicians, and bouquets for the Swiss Guards in the papal parades. They also bought posies for the condemned. For centuries, criminals and heretics were tortured and executed here. Some were hung.

Others were drawn and quartered or thrown into kettles of boiling oil. Most perished at the stake.

The most famous victim was Giordano Bruno, condemned in 1600 for denying the Trinity and the divinity of Christ. The Dominican friar also taught that stars are other suns in the universe. Proud and sarcastic, he accused opponents at a debate in Oxford of “farting out of [their] mouths.” The authorities were determined to muzzle him.

After the death sentence was passed, Bruno’s jaw was clamped shut with an iron gag. His tongue was pierced with an iron spike, and another iron spike was driven into his palate. With his mouth padlocked, Bruno was driven through the streets, stripped naked, and burned at Campo de’ Fiori. Spectators stopped their noses with rose petals or threw lavender sprigs on the flames to kill the stench.

Nineteenth-century liberals made a martyr of Bruno. When Pope Leo XIII denounced Freemasonry, the Grande Oriente d’Italia decided to honor Bruno with a bronze statue. The monument was unveiled, to defiant applause, on June 9, 1889 in Campo de’Fiori. The inscription reads: “A Bruno—il Secolo Lui Divinato—Qui Dove il Rogo Arse.” To Bruno—from the century he foretold—here where the stake burned.

Bruno’s statue stands in the center of the square on the exact spot of his execution. It faces a popular restaurant called La Carbonara. The house specialty is maialino arrosto, roast pork. Smiling couples stop at a flower stand beside the pediment.

Moralists chide because people flirted and haggled as Bruno’s ashes fell like charred petals on Campo dei Fiori. Historians sigh because all glory passes away like a meadow. But poets rejoice because, despite a cruel heritage, Roman lovers still buy roses. Breathe deep and savor their scent. The dead are pollen in the wind.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.