It was a brief throwaway exclamation that made me realize my 3 1/2-year-old son had become one of them.

I’d left him alone in his room for less than a minute, where he was trying to build a gravity-defying skyscraper out of Legos, and as I returned I heard him blurt out, “Ma dai!”

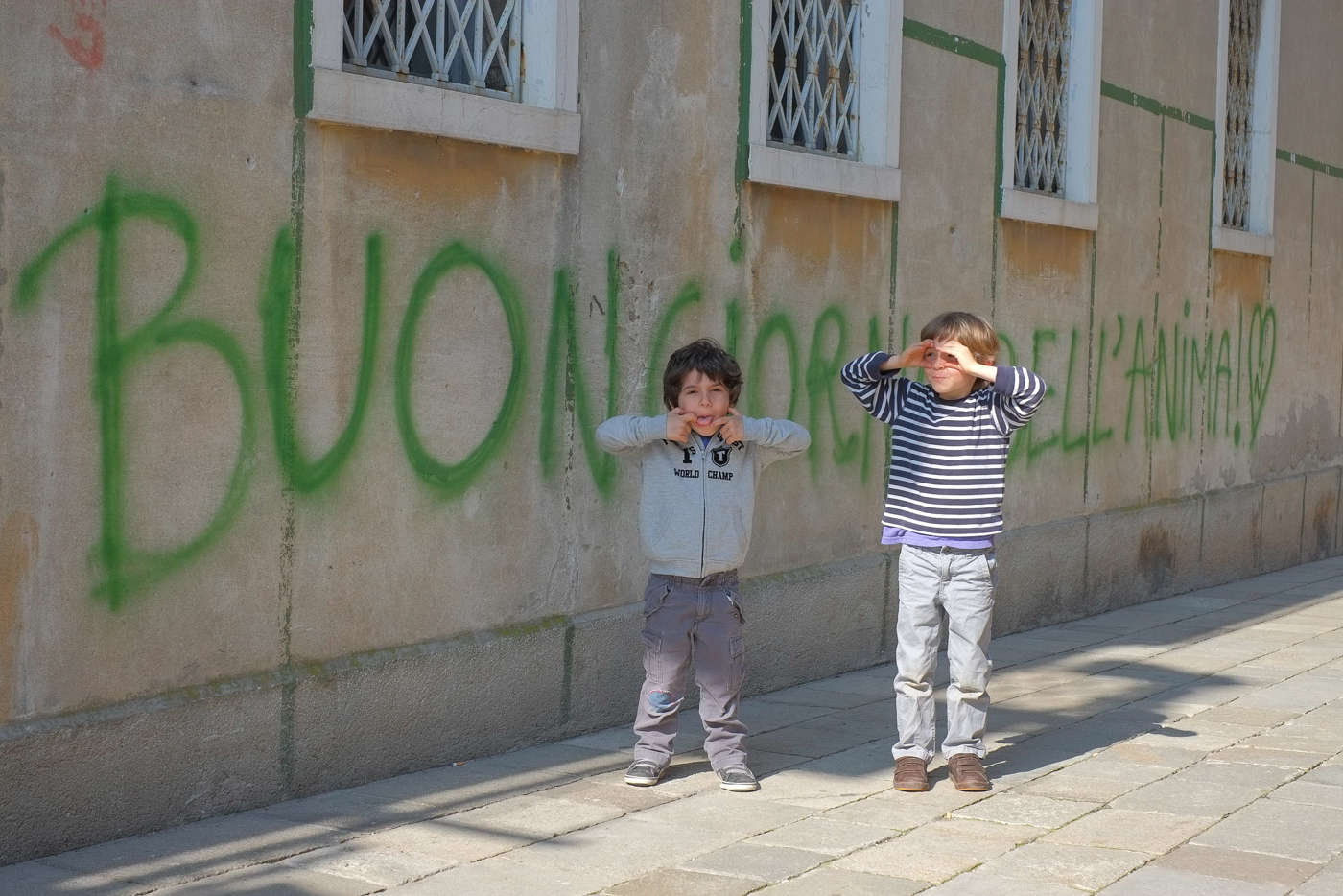

His accent, his intonation, his particular relish of the words on his lips, were exactly that of the adult Italians who live all around us on the island of Sant’ Elena in Venice. He could have been our neighbor Fabio at his workbench, just down the viale. Instead, he was the only child of two mostly monolingual Americans who’d spent the first year and a half of his life in Asheville, NC, the next year in Brooklyn.

My wife Jen and I have lived in Italy with our son Sandro since November 2010. Sandro started public pre-school here a week after we arrived and readily took to his new tongue. Soon, while Jen and I still had to mentally rummage among our store of Italian vocabulary for the right words, Sandro seemed to lightly carry a bunch of the most useful terms in his front pockets, tossing them out as needed like bright small change.

His first sentence in Italian was “Non si fa”. One does not do that, he told Jen, wagging his index finger exactly as his teacher must have often done at school. At this point he still seemed to be borrowing phrases more than possessing them. And we knew that if we moved back to the States he’d drop them even more quickly than he’d picked them up.

But that exclamation of “Ma dai!” uttered in isolation and with complete spontaneity marked a new phase. I realized right then that neither Jen nor I, no matter how long we live here and how much our Italian improves, will ever be able to say that without self-consciousness. It’s a wonderfully satisfying phrase to pronounce, but it is not, and will never be natively ours. So how could it sound so completely his?

As a child acquires his first language it’s easy for parents to feel that he’s becoming more fully a part of the family, expanding his range of participation in it. Becoming, as we say, “one of us.”

In the case of a second language, though, in which neither you nor your spouse is comfortable, your eagerness as a parent to see your child well underway with it can turn into a sense that he or she is being carried off on a stream whose force you’ve rather badly, and perhaps a little sadly, miscalculated.

It gave me new sympathy for immigrant parents everywhere who must watch with a mixture of pride and some slight unease as their child is swept into the linguistic current of a new (and foreign) culture. It gave me new sympathy for my own grandparents, whose own children—my parents—entered school in California speaking only Italian.

My parents never talked about what that was like for them but, perhaps as a result, neither of them ever saw any value in teaching me or my four siblings their mother tongue. In fact the only remark my father (or mother) ever made that could be construed as relating to their first years of school was when my father mentioned at the height of the Iranian Hostage Crisis that during his boyhood in the small town of Newman, California “Italians were about as popular as Iranians are now.”

Sandro does not face similar sentiments. Unlike the unfortunate case of a Romanian boy we’ve met here, the son of two educated and successful parents who refuses to speak his native tongue because of widespread Italian prejudice against Romania, Sandro’s land of origin is generally admired and its language considered essential in this tourist-based economy.

Moreover, Sandro is not being carried off by a strange new language into a strange new land—as my parents were—but by the mother tongue of every generation of my family except my own, into the native land of every generation before my parents. In an essential way, my son has more in common with my deceased grandparents and my father than I, who grew up with them, ever had. His native sense of the language makes him one of “them” in a way I never was. And never really will be.

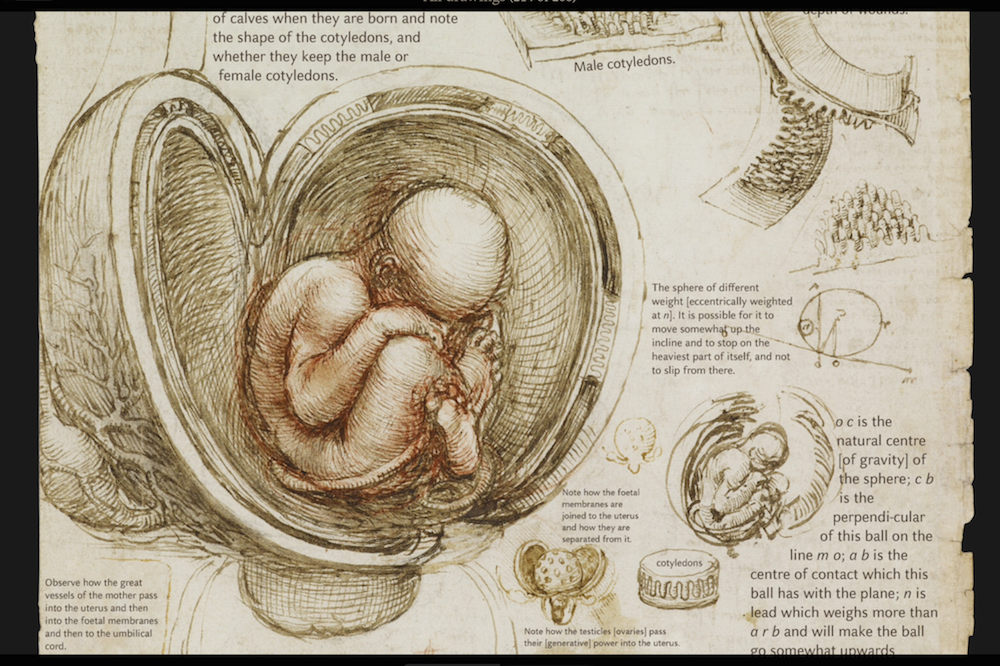

For I come to the language from the outside, as it were, consciously, as something to to be studied and learned, rather than something grown up with, something lived into. Something nearly as natural, or nearly as unconscious, as breathing.

And I know this makes a difference. As the American linguist Benjamin Whorf wrote: “Language shapes the way we think and determines what we think about.”

As the great Italian director Federico Fellini said: “A different language is a different vision of life.”

So what vision of life will Sandro derive from the two languages he now comfortably speaks? There’s no knowing. It’s said that Children are the Future, and no matter how we might try to dictate that Future it’s always ultimately uncertain. But as Sandro’s life moves inevitably forward I’m struck by how, without any special effort on his part, or even awareness, it also circles back in unexpected ways toward origins that my grandparents had resigned themselves to leaving behind forever.

For more about living in Venice, visit Steven Varni’s blog: veneziablog.blogspot.com