Dear Readers,

during the month of February when we traditionally pause to celebrate lovers (Valentine’s Day) and Presidents’ Day. Once Lincoln (February 12) and Washington (February 22) were honored individually; now they are collectively celebrated on Presidents’ Day, February 17.

***

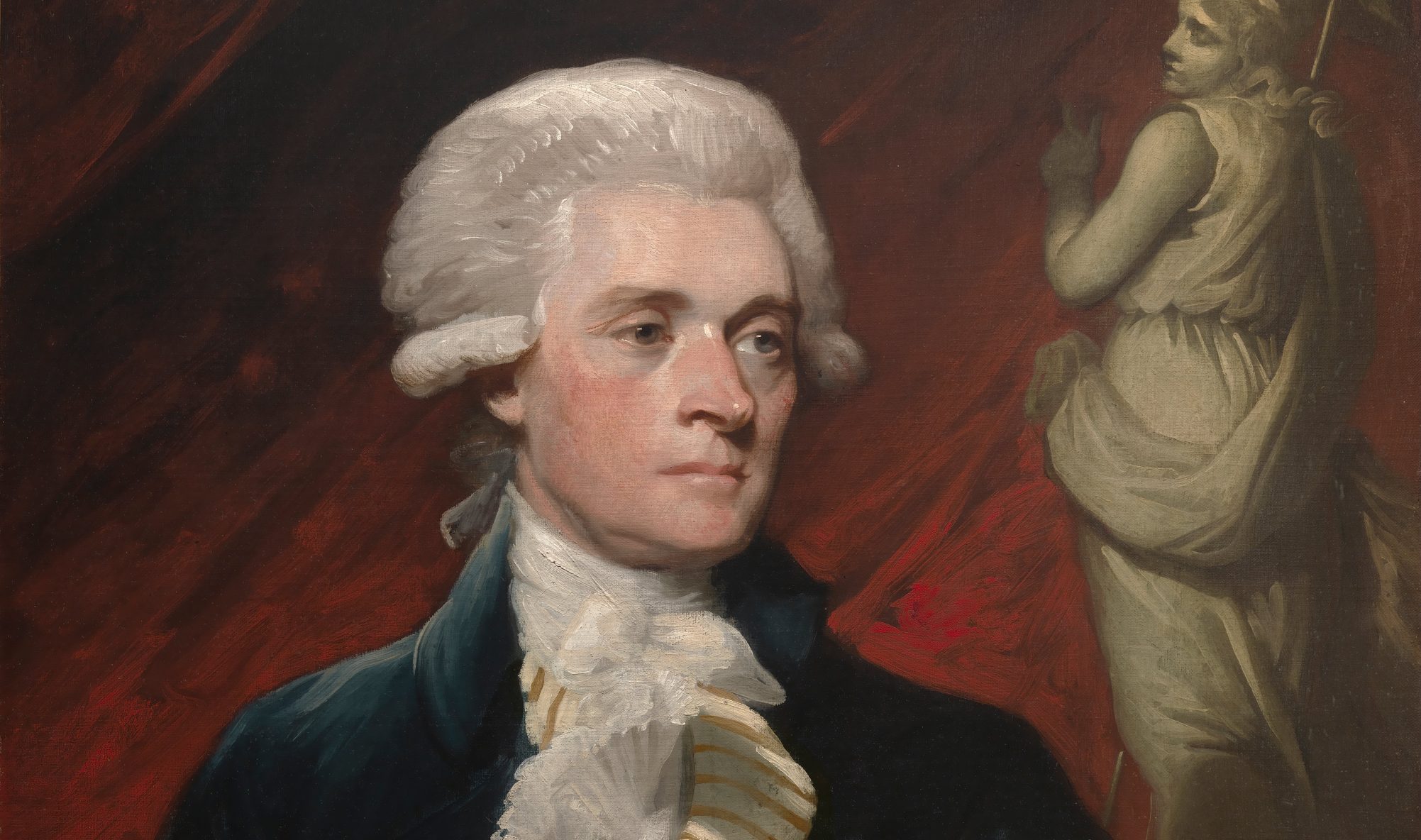

Evidence suggests that Thomas Jefferson had a life-long love for Italy and things Italian as early as 1764, and meeting the beautiful Italian-born Maria Luisa Conway in 1786 merely rekindled this love.

Thomas Jefferson was born in Virginia on April 13, 1743 and died July 4, 1826. He served as our third president from 1801 to 1809. He was 28 years old when he married a young widow, Martha “Patty” Wayles, on New Year’s Day 1772.

He was nearly 40 when his wife died in 1782 (Incidentally, it was Jefferson’s father-in-law John Wayles who had a heavy romance with slave Betty Heming. Thomas Jefferson was mistakenly accused of being her daughter Sally’s father).

Thomas Jefferson was a widower in 1786 when he met the beautiful Maria Luisa Conway. Since his college days, Jefferson had talked and written of his desire to visit Italy, the fountainhead of classical literature and architecture which he considered, more than England, the proper model for the new American republic.

As a young man, prior to 1764, he had studied book-keeping, or “merchant’s accounts” after the “Italian manner” by way of the double entry system described in an early edition of “The American Instructor”.

The inspiration for the layout and architecture of Thomas Jefferson’s mountaintop home, Monticello, are clearly Italian.

There is also ample evidence that Thomas Jefferson’s long conversations with his Florentine-born neighbor, a talkative Italian exile, turned wine merchant named Philip Mazzei, inspired the language used in the Declaration of Independence.

As if by magic, Philip Mazzei appeared at Monticello in the winter of 1774, accompanied by Jefferson’s merchant-agent, Thomas Adams. He became a houseguest at Monticello, brightening up the last two months of 1774 for Jefferson, who had lost his mentally retarded sister Elizabeth, age 29, earlier that year. When a series of earthquakes had rocked the buildings at Monticello on February 21, 1774, Elizabeth had run outdoors in the raw winter weather, and confused, wandered away. She was found dead three days later.

Mazzei, then 43, had been trained as a surgeon in Florence, worked as a ship’s doctor, then practiced in the Middle East before settling in London where he had been a wine merchant for many years. A well-known horticulturalist, he had sailed to Virginia to introduce the culture of grapes, olives and whatever fruit trees would flourish there, and he brought his own crew of Italian vineyard workers with him.

But enough on Mazzei for this column. Back to love interest, Maria Luisa Conway.

According to Willard Randall, author of Thomas Jefferson, A Life, the celebrated Virginian fell in love with Maria Luisa (Hadfield) Conway the moment he met her in early October of 1786, while visiting Paris.

Maria had been born in Florence, Italy, the daughter of the owner of a resort that catered to English travelers. Her parents were English Protestants, but Maria Luisa learned to speak Italian better than English, and having attended convent schools, soon became a devout Catholic.

When she was 17, her father died, and Maria Luisa wanted to become a nun. She even found a convent that would take her in without a dowry. Her Protestant mother, horrified at the idea, quickly took her back to England, where she used her artistic talents to paint miniatures.

When Maria Luisa was 20, her mother, after being offered a lifetime settlement for herself, promised the Botticelli-like beauty in marriage to a stout suitor twice her age, Richard Conway, who had made a small fortune painting pornographic miniatures for noblemen on snuff boxes.

Thomas Jefferson had been widowed for four years, faithful to a vow he’d made to his wife on her deathbed that he would never remarry so that their two daughters, Patsy and Polly would not be raised by a stepmother, as she had been. There is no hint that he even had the briefest liaison with any of the many French women he’d met in Paris.

But no sooner was Jefferson introduced by an artist friend to Maria Luisa, than he began to devise how he could spend every possible moment with this lively, beautiful lady.

Soon he was contriving to develop projects with an “Italian connection” to prevent prolonged separations, i.e., a possible visit to view art in her birth city, Florence; brushing up on his Italian conversations, now rusty since the departure of his neighbor Mazzei.

However since Signora Conway inconveniently already had a husband who had business to attend to in England, and Thomas Jefferson has business in the United States, the romance was just one of those things, and remained a happy memory for lifelong Italophile, Thomas Jefferson.

***