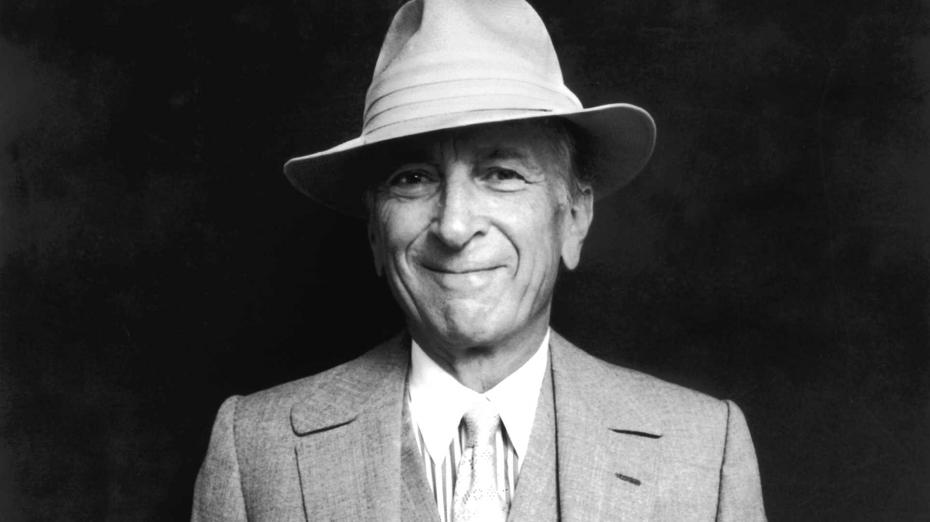

The American media and the government’s vacillating policies toward immigration over the past century have contributed to many like Gay Talese to question his cultural identity as an adolescent growing up in Ocean City, New Jersey during World War II. He described when his father prepared packages for his relatives in Italy, and while “I waited in-line to mail the parcels, there were US propaganda posters of Mussolini, Hitler and Hirohito.”

Gay stopped in mid-sentence, sat further back, fully stretched his legs out and rested his feet on a marble table across from the two leather couches that we were both sitting on, and said, “The posters made me think, am I American, or Italian or even an enemy alien.” The negative images and disparaging remarks forced Gay to search unknowingly for someone who could be that bridge between the writer’s American side as well as his Italian side.

While I listened attentively to his story, we were briefly interrupted by the Talese’s dog walker. What timing I thought, I could sense that prior to the arrival of the canine assistant, Gay was about to add an interesting layer to his response of how he handled his confused and defensive state of mind while growing up in Ocean City, during World War II.

The dog walker greeted Gay from across the hallway and proceeded to go upstairs to get the dogs. The writer then turned to me and asked if I wanted to cease recording for a few minutes until the dog walker brought the dogs down for their daily routine. Gay was concerned about me wasting the minutes of my recorder, but many recorders today are digital and can store over four-hundred hours of memory.

I replied, it was fine for the recorder to continue and more importantly, “it’s all part of the experience.” He willingly agreed and immediately responded, “So as I was saying, all these negative images of Italians as well as my parents almost living two lives made me conflicted. And that’s when he followed up and said, “I remember hearing Frank Sinatra on the The Lucky Strike Hit Parade for the first time.” He stopped, turned his head upward and remained silent as he reflected upon this turning point in his adolescent life.

After a few seconds, he made eye contact again, cleared his throat and continued, “Thanks to Sinatra’s music, I realized I could be an American. Sinatra was an interesting contrast, he was a main line success story and was not a gangster or ballplayer or boxer he was an Italian American who appealed to all Americans from coast to coast and he gave me a reason to be proud to be Italian American.”

Ironically, after Gay Talese decided to move on from his sports writing days for the New York Times (1955-1965) he moved on to Esquire and wrote Frank Sinatra Has A Cold published in 1966, the article catapulted his literary career to a different stratosphere. It was one of his first assignments for the magazine and one of the most challenging because Sinatra rarely gave interviews and likewise never agreed to be interviewed by Gay for his literary profile that in 2003 Esquire editors voted “Best Story Esquire Ever Published.”

The article is classic Gay Talese in that what separates his approach and technique from most writers is that he wants to “hang out” with the person he is profiling in order to capture the true essence of the interviewee. He used the “hang out” method to conduct extensive research on notable personalities including: Joe Louis, Floyd Paterson, Joe DiMaggio, Peter O’ Toole, Muhammad Ali, Jose Torres, and Joe Girardi. He was the first author to write about the Mafia while hanging around for several years with the late Mob Boss Joe Bonanno, and his son Bill. The experience turned into the book Honor Thy Father. At the same time, he also finds the common person just as intriguing as celebrities and wrote The Bridge about blue-collar workers involved with the building of the Verrazano Bridge.

In Sinatra’s profile, he followed and observed Old Blue Eyes for three months and interviewed Sinatra’s inner circle and family members like Frank’s mother Dolly. In Frank Sinatra Has A Cold he writes, “When many Italian names were used in describing gangsters on television show, The Untouchables, Sinatra was loud in his disapproval.” Frank Sinatra’s positive image taught Gay to have pride in his Italian American culture.

The writer experienced another revelation about his Italian heritage when he traveled to

taly in 1955 while he was on furlough from his army unit based in Germany. He realized parallels between America’s South and Southern Italy. Gay had attended the University of Alabama as an undergraduate and witnessed America’s segregated south and culture. “What connects Italian southerners with American southerners is their lingering sense of separateness” he opined. Moreover, he reinforced this idea by explaining that his father identified his ethnicity as Calabrese not Italian.

“In many ways” he paused and started to rub his eyes, “the beauty of southern Italy, its rural landscape and slow pace, reminded me of Alabama.” He continued to learn more about southern Italian history when he did research in the early 1990s for his autobiographical book Unto the Sons. At this point I sensed we were approaching the end of our discussion as he started to rub his eyes more frequently before he recollected on his Italian American journey.

My “hang out” session with the acclaimed author lasted nearly two hours in between a window repair crew, dog walker and an occasional telephone ringing from his land-line. The calls were for his wife. Gay, who still maintains a home in Ocean City, was very gracious and open about his Italian American experience. His articles like the Sinatra piece is studied in journalism school for its unique reportorial writing style that includes elements of fiction through storytelling with reality as its foundation.

The genre is referred to as New Journalism and thanks to his friend and writer Tom Wolfe, the author is known as the father of New Journalism. Although he is grateful for Tom Wolfe anointing him the creator of this literary category, he does not want the title. My interview with Gay Talese motivated me to reread many of his articles, especially the Sinatra piece, and through his words, I faintly heard the little boy inside who was struggling to understand what it meant to be an Italian American growing up in Ocean City.