Chiacchiere, bugie, frappe, and cenci. No matter the name, they are a similar Carnival snack—thin, deep-fried strips of a liqueur-enriched dough that are tossed in sugar and munched upon during the festivities. In Venice, arguably home to Italy’s most famous Carnival celebration, they’re known as crostoli or galani. But these aren’t the only sweets worth their weight in zucchero for this occasion. Yeasted doughs fried in oil produce mouth-watering sugar-dusted fritters, and dessert dumplings show up as hearty and sweet ravioli, or tortelli, often deep-fried and stuffed with dried fruits, chocolate, nuts, and sprinkled with extra sugar…or marzipan.

Venice’s galani and frittole take center stage during Carnival. The former are made of flour, butter, sugar, eggs, and grappa or white wine, then are deep-fried to produce crispy and flaky results. Frittole are the quintessential fried donut made of a yeasted flour dough with the addition of eggs, sugar, lemon zest, raisin, and pine nuts. In the 17th century, frittole were chosen as the national dessert of the Venice Republic. They were prepared by fritoleri, who set up shop on the streets in little wooden huts. About 70 of them formed a union-like organization ensuring that they and their families could maintain their businesses in specific locations throughout the streets. Ultimately, this organization was dismantled, but the treat remains a classic eaten today.

Veneto’s quieter neighbor, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, has similar sweet traditions that are influenced by bordering countries Austria and Slovenia. The impact of these cultures affects local holiday rituals during the Carnival period as well.

In the mountains of Udine near the Austrian border sits Sappada, a small village where Carnival bears witness to folkloric processions and desserts that sound more German than they do Italian. Also known as Plodar Vosenòcht in dialect, the longstanding Carnival tradition calls for participating locals to dress up as the fear-provoking character Rollate. Sporting a large black fur with a red wool headpiece, the Rollate wear wooden masks to disguise the faces and voices of the people behind them. These figures carry brooms and dance through town on the three Sundays preceding Lent, otherwise known as Domenica dei Poveri, Domenica dei Contadini, and Domenica dei Signori. They also hand out mogn kropfen, a tortelli dumpling stuffed with poppyseed and honey. Another festive food is the Hosenearlan, or orecchiette di coniglio (rabbit’s ears), ravioli made with a mix of corn and wheat flours, butter, eggs, sugar, and a touch of grappa and lemon.

Nearby Sauris celebrates with a similar tradition. Some locals masquerade as Rölar, whose faces are smeared with soot, and others as Kheirars, who wear wooden masks. Also a German-speaking village, Sauris sits at about 3200 feet above sea level, and very little produce grows there naturally (apart from a wild plum tree that produces fruit for a short period, everything else must be imported). One of the only traditional desserts made here for Carnival – and weddings or other festivities – is vledlan, a fritter prepared with flour, sugar, eggs, grappa, and some locally grown wild mint or sage.

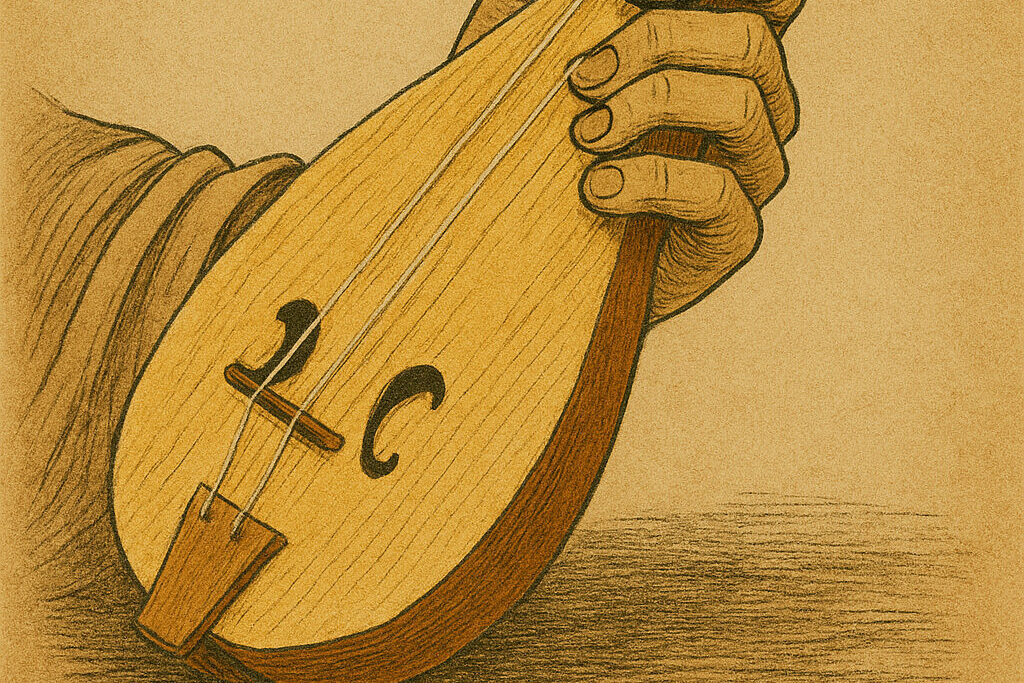

Only 40 miles to the east, near the Slovenian border, yet another small town holds a traditional Carnival procession, this one featuring beautiful white masks and “ugly” masks. Festivities include dancing to the tune of the cïtira (violin) and the bünkula (cello), munching on sope, a mini French toast-like piece of bread dipped in egg, then pan-fried and sprinkled with sugar, and consuming bujarnik, a fruit cake made with corn and wheat flours, dried fruits like raisins, nuts and figs, apples or pears, and a touch of fennel seeds or cinnamon for a unique flavor.

Just south of Trieste, in Opicina, one will find an even more unusual Carnival fritter—le frittole con l’anima, or fancli z duso in Slovenian dialect. These savory beignets are made with a dough enriched with grappa or acquavite, flour, eggs, oil, and white wine, and stuffed with anchovies, as that was the regular catch in the nearby fishing village from which they hail.

This same region is known for its strucchi fritti, little doughy treats stuffed with a rich mixture of nuts, hazelnuts, raisins, pine nuts, lemon zest, cinnamon, rum, and grappa.

There are some notable Carnival fritters popular outside of Friuli-Venezia Giulia as well.

In Abruzzo, ravioli dolci teramani are traditionally served during Carnival days, noted for the preparation of a sweet ricotta filling (sheep or cow’s milk are acceptable), and a touch of cinnamon. These lightly sweetened dumplings can be eaten with either a meat and tomato sauce, butter, and sage sauce, or simply with some sugar and cinnamon.

In Liguria, Carnival is celebrated with a ravioli trompe l’oeil—these dumplings will satisfy a real sweet tooth. They can be filled with anything from almond paste to jam, or fruit and nuts. However, the classic “scherzo” for Carnival is a traditional preparation of almond paste-stuffed ravioli served in a “tomato sauce” (marmalade) and topped with “parmigiano” shavings (marzipan). The story goes that Genovesi monks developed this recipe to satisfy their cravings for sweets during Lent, when animal products were not allowed to be consumed. Today in Liguria, many variations of these ravioli dolci appear throughout the year as well.

From Venice to the villages of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and beyond, there is no better way to savor Carnival than through a snacking tour of its sweet treats.