On Sunday, March 23, the Museo Italo Americano was packed to the limit with a Standing Room Only crowd. The occasion was the 20th Anniversary of the 1994 opening of the WWII exhibit, Una Storia Segreta: When Italian Americans Were ‘Enemy Aliens,’ which also played to SRO crowds at the Museo twenty years ago.

After that initial showing, the exhibit went on to be displayed in state houses, city halls, libraries and Italian American venues nationwide—some 53 different sites in all at the last count. Most important of all, following the exhibit’s appearance in the Rayburn House Office Building in Washington, DC, Representatives Rick Lazio and Eliot Engel introduced legislation calling upon the U.S. government to finally acknowledge that these events had taken place and that the civil liberties of Italian Americans had been systematically violated.

On November 7, 2000, the Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act was indeed signed by President William Jefferson Clinton, and became Public Law #106-451. All this from an exhibit that was initially considered “of limited appeal” by the California Council for the Humanities when they rejected a grant application to sustain it, thus leaving it to sustain itself with grass-roots support from the Italian American community—which it did for twenty years.

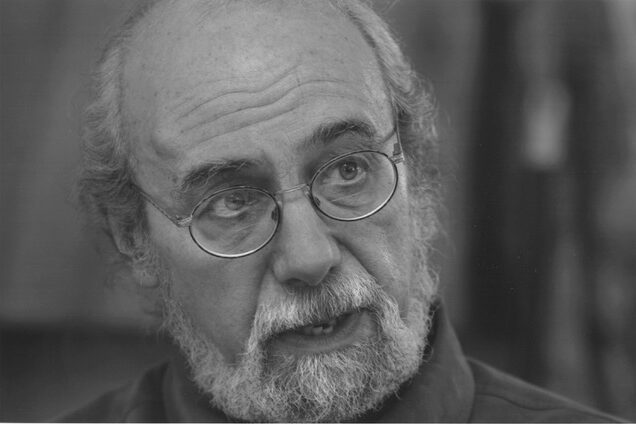

Sunday’s event did not present the original exhibit. But the speakers— Adele Negro, President of the Italian American Studies Association, Western Chapter, which created the exhibit; Lawrence DiStasi, Project Director and author of Una Storia Segreta: The Secret History of Italian American Evacuation and Internment During World War IIL’Italo-Americano and the person who first broached the idea of an exhibit; John Buffo, Pittsburg CA historian whose grandparents were forced to evacuate from the prohibited zone that included all of Pittsburg; and Richard Vannucci, whose uncle in San Francisco was so distraught by the curfew that kept him home-bound that he died of a ‘broken heart’—along with the slide show that presented images of the original exhibit panels and some of the details of those panels, seemed to excite the fascination of the crowd.

Numerous questions and comments from the audience followed the presentations, indicating that interest in this issue remains as high today as it was twenty years ago. So does the fact that in the last month, several requests to host the exhibit have come in from universities in various parts of the nation.

The theme announced at the event by Lawrence DiStasi was simple: the coming together of Italian Americans and their organizations throughout the United States to promote the exhibit itself, and to work to pass the legislation introduced in 1997. Both these aspects were successful. A related theme was recovery: recovery in the sense of recovering/uncovering the basic facts that had been buried for so long; and recovery in the sense of recovering from the repression that had hidden those facts, even from those who went through them, for so many years. Both themes—unification and recovery—stood in vivid contrast to the effects of the restrictions at the time, which was to scatter and/or isolate Italian Americans nationwide.

Indeed, at the May 1942 Tenney Committee hearings in San Francisco, one witness urged the committee to take measures (shutting down newspapers, clubs, even banks) that would induce Italian Americans in San Francisco and other Little Italies to “forget” their Italian-ness and “enter the American way of life.” By contrast, Una Storia Segreta provides the Italian American community, and Americans in general, with the occasion, each time it appears, to remember.

Whether Una Storia Segreta will travel for another twenty years is unclear. But it is certain that an issue that directly affected 600,000 Italian immigrants branded “enemy aliens” during the war, and thousands more related to them, still retains the rare capacity to educate, inspire, and move.