A solitary woman dressed in dark regal hues, her fingers adorned with topazes and opals, a voice as deep and smooth as the softest of velvets. She sits in a room scented like opium and incense, twilight cloaking everything in purple and orange. In front of her, there they are: beautifully decorated, colorful, mysterious, frightening.

This is what comes to mind when the word “tarots” is mentioned. The more informed about the topic would probably also recall specific illustrations, those of the incredibly famous Rider-Waite deck, created in England at the beginning of the 20th century. But our story today — and indeed that of tarots in general — starts much earlier than that. Indeed, history and tradition both tell us that tarots are an Italian invention. Playing cards made their way into the Belpaese thanks to its commercial contacts with the Middle East, all the way back during the early decades of the Renaissance. The Mamluks were keen players and the Italians, never to be underestimated when it comes to having fun, liked those cards so much they decided to make them theirs. This is how the history of tarots starts; then 22 anthropomorphic cards, the major arcana or, to call them as they used to then, trionfi, were added to the middle eastern deck and i tarocchi were born.

In 2009, the Sola-Busca deck was acquired by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and it is today part of the Pinacoteca di Brera collection, in Milan

They are first mentioned in a letter by lawyer Giusto Giusti of Anghiari dating back to 1440, and records of their presence at the Este court, Ferrara, in 1442 are also found. They are shown in a late 15th century fresco in Palazzo Borromeo, in Milan, and there are partial decks dating back to those very years: we have the Visconti di Modrone tarots, today preserved in the US, at Yale, or the beautifully illustrated Brera Brambilla tarots, of which, however, only two major arcana survive. Then we have the Visconti-Sforza tarots, a more complete deck, probably created around the mid-15th century.

The first peculiarity of the Sola-Busca deck is its major arcana

Beautiful decks indeed, but all missing some cards.

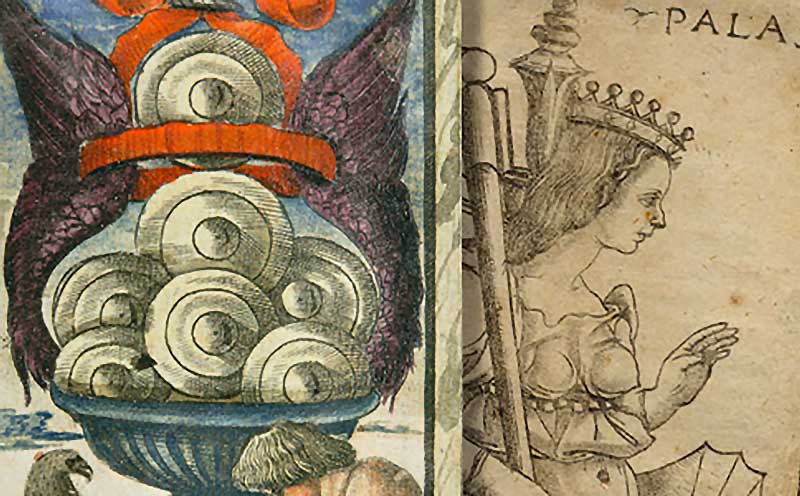

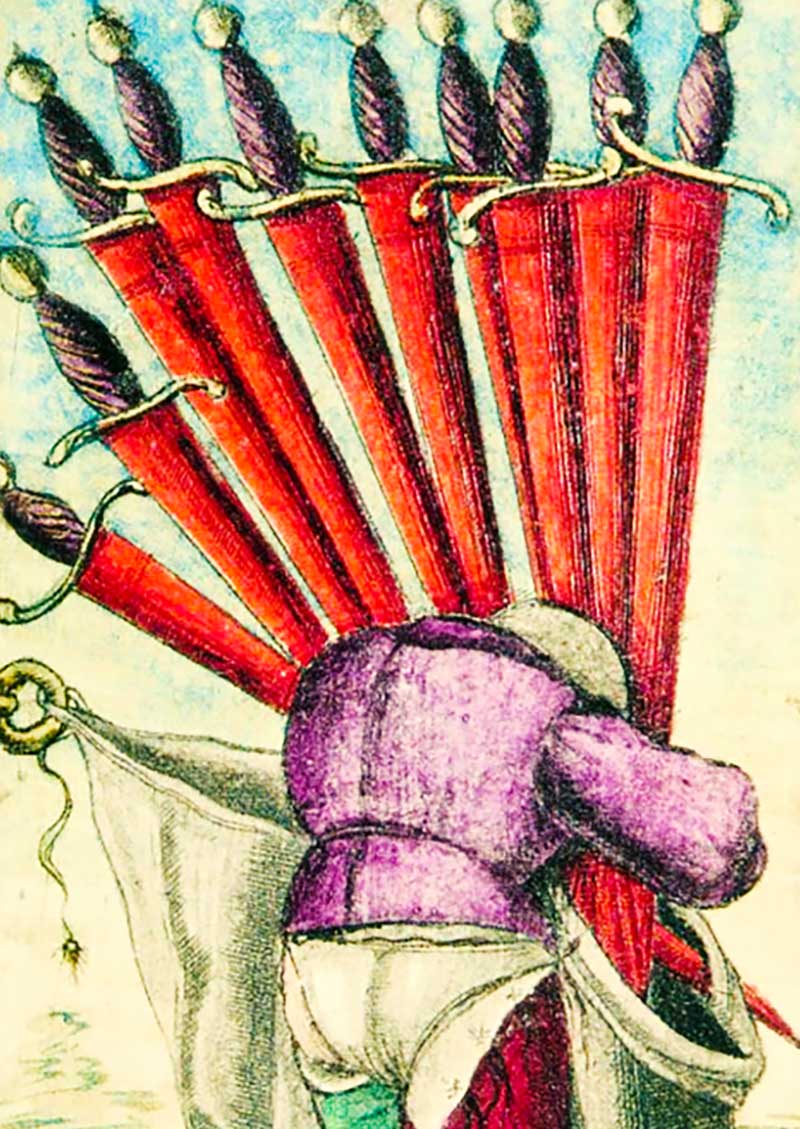

To see them all, preserved and beautifully illustrated, we have to look at the Sola-Busca tarots, the oldest complete deck existent in the world. These cards are much more than a game and even more than a piece of art: there is mystery and secrecy behind them, and esotericism even before the association between tarots and magic was created (We’ll have to wait until the 19th century to see that happening). A tad of history first: the deck gets its name from those of its last two owners, Marquise Busca and Count Sola, and were probably produced between 1470 and the beginning of the 16th century. It comprises 78, beautifully illustrated cards, 22 major arcana and 56 minor arcana, engraved on cardboard and hand painted with tempera colors and gold.

The first peculiarity of the Sola-Busca deck is its major arcana: in them, Classical and Biblical figures take the place of traditional tarot illustrations: for instance, the arcana of justice is Nero and that of the world is Nebuchadnezzar. Among others represented Gaius Marius, uncle of Julius Cesar, and Bacchus. There are also other not as simple to identify figures, such as the Carbone of the 12th arcana, which some associate with late 15th century humanist and literary man Ludovico Carbone, who was part of the Este court in Ferrara. Minor arcana are also different from all other decks’, because they are finely and richly illustrated with scenes of daily life: a true piece of art.

They are first mentioned in a letter by lawyer Giusto Giusti of Anghiari dating back to 1440

We were talking about mystery, though, and the Sola-Busca deck is certainly mysterious. Indeed, Italian researcher Sofia di Vincenzo managed to prove the existence of a link between the deck and the hermetic-alchemical thought of the Renaissance. This is particularly evident in the suit of coins, which apparently illustrates the process of coin minting, but in reality alludes to the complex and secret practices of the Opus Alchemicum, that is, the method used to create the lapis philosophorum, the philosopher’s stone, alchemic instrument of immortality and perfection. If there were need for any more proof, the ten of coins card holds it: on it, the figure of a man wearing a turban, open reference to Hermes Trismegistus, legendary figure of the Hellenic period and author of the Corpus Hermeticum, the core text of the ancient philosophy of hermeticism, and inspiration for a plethora of later esoteric texts.

The Sola Busca tarot deck, the oldest complete deck extant, is known for the beauty of its illustrations

And if this wasn’t enough mystery for a day, there is more. In spite of the refined and delicate artistry behind their illustrations, the name of the man, or men, who created them remained shrouded in darkness for centuries; in 1938, Arthur Mayger Hind mentioned the Sola-Busca tarots in his work about Renaissance engravings, attempting to date them and to name their author; his analysis of the images and of some inscriptions led him to believe they were engraved in 1490 and painted a year later, in 1491. He also maintained they were probably created for a Venetian, as witnessed by references he found to the Republic within some of the drawings. The name of the artist behind their creation? Mayger Hind mentioned Mattia Serrati da Cosandola, an engraver from Ferrara. However, other theories exists. More recently, the hand of Ancona painter Nicola di Maestro Antonio has been recognized behind the engravings, while the coloring has been attributed to Venetian humanist and historian Marin Sanudo.

Playing cards made their way into the Belpaese thanks to its commercial contacts with the Middle East

What an incredible story, that of the Sola-Busca tarots. And it isn’t finished.

For more than four centuries they remained the only complete deck of tarot cards with anthropomorphic, dynamic figures on them: this, along with some outstanding pictorial similarities, brought a number of esotericism experts to state the Sola-Busca tarots were the inspiration behind Pamela Colman Smith’s own work for the Rider-Waite deck, the most famous tarot deck in the world.

In 2009, the Sola-Busca deck was acquired by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and it is today part of the Pinacoteca di Brera collection, in Milan.