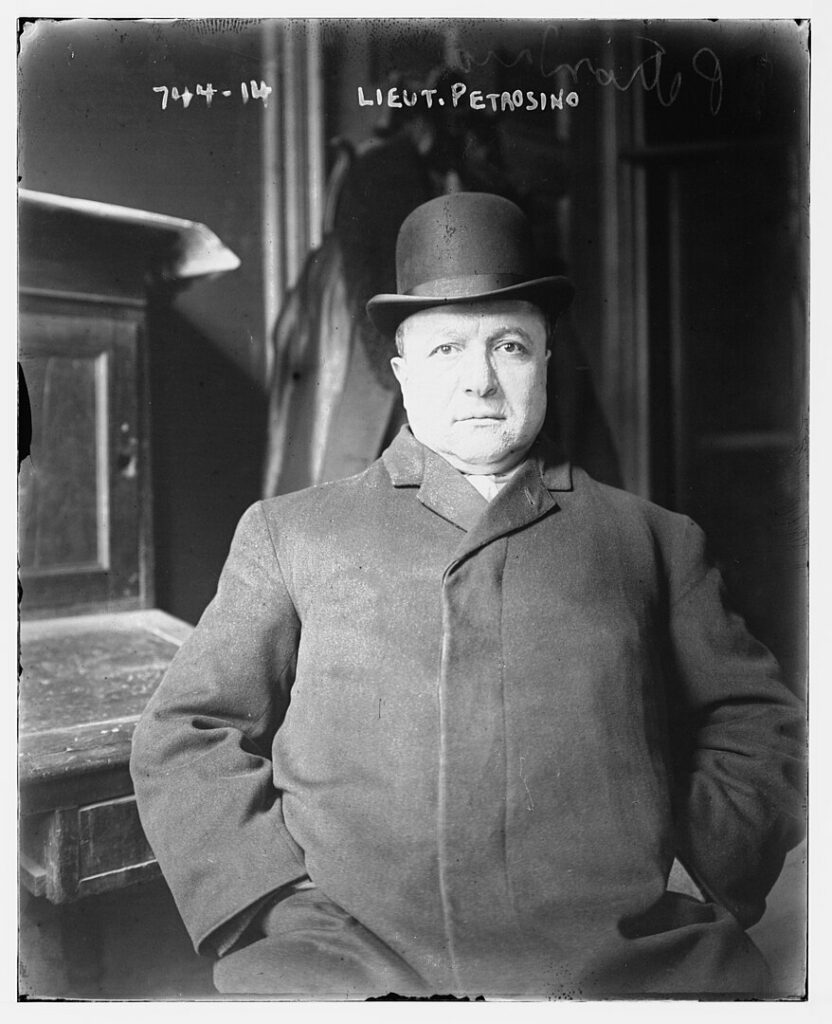

Who knows what the weather was like at 8:45 p.m. on that Friday, March 12, 1909, in Palermo? A few people stood at the tram terminus in Piazza Marina when the sudden crack of four gunshots shattered the evening calm. Panic swept over them. Some ran, others froze in place. Only one man — a sailor from Ancona named Alberto Cardella, who had just disembarked from the Regina Nave Calabria — rushed toward Villa Garibaldi, the source of the shots. He arrived just in time to see a man collapse to the ground as two shadowy figures disappeared into the darkness.

The bullets had struck their target with deadly precision — one in the neck, two in the back, and a fatal shot to the head. There was no chance of survival. By the time help arrived, it was too late. The man lying on the ground was Joe Petrosino, a police officer— the first in law enforcement to be assassinated by the Mafia. He had been on a top-secret mission from the United States, but a press leak had led the New York Herald to publish all the details of his trip. Despite the exposure, Petrosino believed that, just as in New York, the Mafia in Palermo wouldn’t dare kill a police officer. Unfortunately, he was wrong. His mission to dismantle the Mano Nera — the criminal network he had correctly traced back to Palermo — came to a brutal end that night. He was just 49 years old.

“Petrosino shot dead in the city center tonight. Assassins unknown. A martyr has fallen.” With these words, the American Consul in Palermo sent a telegraphed report of the Mafia execution to the U.S. government.

Giuseppe Petrosino was born on August 30, 1860, in Padula, a town in Italy’s Campania region, in the province of Salerno. His father, Prospero, was a tailor who managed to provide an education for his four sons — one of the few families in town to do so — with the help of a private tutor. In 1873, the Petrosino family emigrated to the United States, enduring a 25-day voyage by ship before arriving in New York. They settled in Little Italy, where young Giuseppe grew up. As the eldest child, he felt a strong responsibility not to burden his family financially but rather to contribute to their livelihood.

Determined to adapt to his new country, he attended evening classes to learn English while working various jobs. He started as a newsboy, selling newspapers on the street, then shined shoes as a sciuscià (shoeshiner). By 1877, now going by the name Joe, he had obtained U.S. citizenship. The following year, he took a job as a street cleaner and quickly worked his way up to foreman.

On October 19, 1883, Petrosino joined the New York Police Department. The silver badge pinned to his uniform bore the number 285. After a brief period patrolling 13th Avenue, his sharp instincts, intelligence, and unwavering professionalism earned him promotions to more significant roles.

In the meantime, waves of Italian immigrants were arriving in growing numbers. By early 1906, Joe Petrosino, now head of the Italian Branch — a special police unit tasked with dismantling the extortion network known as the Mano Nera(Black Hand) — submitted a report to the director of the New York Police Department. In it, he wrote: “The United States has become the dumping ground for all of Italy’s criminals and bandits, particularly from Sicily and Calabria… They now thrive here, living off extortion, robberies, and all manner of illicit dealings.”

Fluent in multiple Italian dialects, Petrosino used his linguistic skills to his advantage. After serving as a patrol officer, he earned a position in the investigative unit, eventually rising to the rank of sergeant-detective. Early on, his colleagues didn’t make it easy for him. His surname, Petrosino, was a dialectal version of prezzemolo (parsley) in southern Italy, a detail that became the butt of many jokes in the precinct. His physical stature didn’t help either — he wasn’t particularly tall or athletic. But what he lacked in size, he more than made up for with intelligence, and that proved invaluable in his work.

Taking down the Mafia — at the time still widely referred to as the Mano Nera — became his life’s mission. The Italian-born officer, known for his integrity and devotion to his family — he was married with a young daughter — even earned the respect of the President of the United States. In 1895, none other than Theodore Roosevelt, a close friend and admirer, appointed him Sergeant. A decade later, in 1905, when Petrosino was promoted to Lieutenant, he was placed in command of the Italian Legion, a unit specifically assigned to combat the Mano Nera. Using disguises, undercover operations, and daring tactics, he managed to bring down criminal bosses previously considered untouchable, elusive, and beyond the reach of justice. He was also one of the first to recognize the deep ties between the American Mafia and its Sicilian counterpart. He believed that to truly weaken organized crime in the U.S., the fight had to start in Sicily.

That conviction led him to embark on a secret mission to Palermo, a trip financed by powerful bankers like John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan. Petrosino checked into the Hotel de France, located in the very square where he would later be assassinated. But secrecy was short-lived. The New York Herald leaked the news of his journey —along with other sensitive details — sealing his fate before he even set foot on Sicilian soil.

Petrosino had warned the 25th President of the United States, William McKinley, about a plot to assassinate him — an attack ultimately carried out by a young anarchist on September 6, 1901, during the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. But his warning went unheeded. This was the same Joe Petrosino who, in 1903, solved the infamous “Barrel Murder” case, so named because the victim, Benedetto Madonia, had been found dismembered and stuffed inside a barrel. The same man who was received by Italy’s Prime Minister, Giovanni Giolitti, who gifted him a gold watch in appreciation. And the same man who, after his official duties, made time to visit his brother Michele, who had left America to return to Italy.

That same Joe Petrosino was ambushed in Palermo on March 12, 1909 — shot in the back by two assassins who disappeared into the night.

His autopsy, conducted by Dr. Giovanni Liguori on March 14, confirmed the cause of death: gunshot wounds. Despite a large bounty placed on his killers, they were never officially identified. Petrosino was honored with two state funerals, one in Palermo on March 19, and another in New York on April 12. It is said that around 250,000 people attended his funeral procession. A plaque in his memory stands in Palermo, affixed to the wrought-iron fence surrounding the Garibaldi Garden in Piazza Marina, the very spot where he fell to Mafia bullets. On the 150th anniversary of his birth, the Italian postal service issued a commemorative stamp in his honor.

Fitting tributes to a man who remains celebrated across two continents: Lieutenant Giuseppe Joe Petrosino, a hero never forgotten.