On December 24, 1914, a dejected Pope Benedict XV cel- ebrated midnight mass in St. Peter’s Basilica. His efforts to secure a Christmas truce had failed.

A 400-mile trench stretched from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border. Some British and German troops near Ypres had stopped killing each other long enough to play soccer in No Man’s Land.

Most soldiers, however, were quite willing to butcher one another on Christ’s birthday, with the full blessing of flag-waving clerics.

“May the guns fall silent at least on the night the angels sang!” Benedict had pleaded. He might as well have preached chastity at an orgy. “Why not Easter?” scoffed Joseph Joffre, Commander-in-Chief of the French army. “Why not Yom Kippur?” Benedict’s aides advised him to ignore this out- burst. Obviously, Marshall Joffre had never recovered from the Dreyfus affair.

During Christmas Eve service, the Curia scrutinized the Pope’s performance. Beneath Bernini’s bronze and gold baldacchino, he was as gawky as a curate at his first mass. He sighed and fumbled at the altar. His shoulders slumped. His hands shook. The acolytes exchanged embarrassed glances. Never had His Holiness seemed so frail and small.

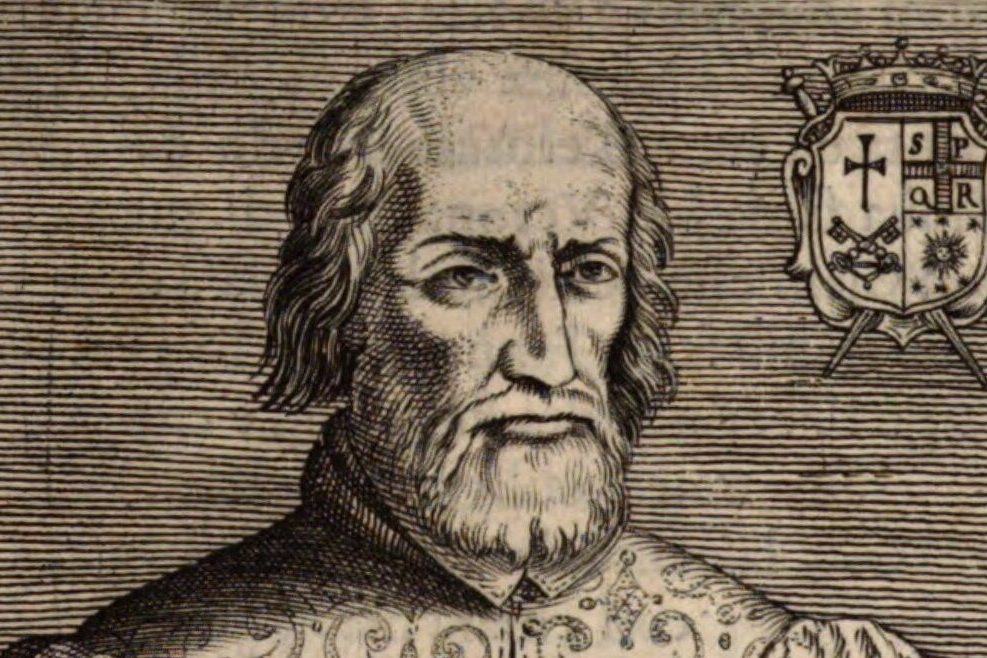

The faithful called Benedict Il Piccoletto, the Little Guy. Tailors had to prepare the smallest of the three papal cassocks at his September 7 election. Raised in a noble Genovese family, Giacomo della Chiesa was dignified in bearing and courtly in manners, but his appearance was hardly pontifical. Sallow and stunted, he was cursed with matted hair and buck teeth. His eyes and nose, chin and neck were crooked. Milkmen blamed rick- ets to boost sales. A contractor compared the new pope to a carpenter’s ruler: “You could fold him up in sections and put him in your pocket.”

Whatever his physical defects, Benedict was the only world leader who realized the grim implications of the Guns of August. In Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, his first encyclical published on All Saints Day, 1914, he called the Great War “the suicide of civilized Europe.” The West’s most powerful and prosperous nations had provided themselves with the most awful weapons mod- ern military science had devised. “They strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror,” said Benedict. “There is no limit to the measure of ruin and slaughter. Day by day, the earth is drenched with newly shed blood and covered with the bodies of the wounded and the slain.”

Secular authorities ignored him, particularly in Rome, where demagogues proclaimed that only violence would save civilization from communism and canned ravioli. Less than four months after the Pope’s first Christmas mass, Italy declared war on Austria- Hungary. Nearly 700,000 men would die at the front.

Horrors and portents followed. The Ottomans launched the Armenian Genocide. The Madonna appeared at Fatima. The Russian Revolution exploded. Before the disaster of Caporetto, a desperate Vatican issued a seven-point peace plan.

Benedict proposed an immediate ceasefire, a lowering of armament stocks, guaranteed safety on the seas, international arbitration, and compensation for confiscated property. Italian politicians accused him of conniving to restore the Papal States. Foreign leaders suspected his neutrality. Both the Allies and the Central Powers were convinced that he was biased towards the enemy.

When the war ended, President Woodrow Wilson, whose Fourteen Points plagiarized Benedict’s plan, kept the Pope away from Versailles. What place was there for a pacifist at a peace conference? For that matter, what place was there for a saint at the Vatican?

Benedict was notoriously generous, helping poor Roman families with cash gifts from his private revenues. When the money ran out, prelates instruct- ed petitioners at papal audi- ences not to mention their financial woes. During the war, Benedict had donated millions in church funds to the Save the Children Foundation. All that remained in the Vatican treasury was the equivalent of $19,000. The bankers would have poisoned him, if he had not fallen ill.

On December 21, 1921, the anniversary of his ordination, Benedict celebrated mass with the nuns at St. Martha Hospice.

While awaiting his driver in the rain, he caught the flu. Pneumonia developed. After a month of agony, he died on January 22, 1922 and was interned in the Vatican grottos. Six years later, a monument was erected in St. Peter’s.

Benedict’s statue prays in front of a bronze relief of the Madonna and Child. Wearing a simple skullcap rather than the triple tiara, the Pope of Peace kneels over a casket of a fallen soldier. His face is careworn but kind. Baby Jesus waves an olive branch over a world gone up in flames.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.