The list of honorees reads like a who’s who among Seattle’s culinary elite: Armandino Batali of Salumi; food marketer Jon Rowley; Frank Isernio, founder of Isernio’s Sausage; restaurateur Tom Douglas and his wife Jackie Cross; and most recently, Charles and Rose Ann Finkel, legendary brewmeisters and founders of Pike Brewing Company.

These are just a few of the past winners of the Angelo M. Pellegrini Award, begun in 2006 to honor Seattle’s culinary legend, who died in 1991 at the age of 88. The award is given to an individual or couple each year who has made significant contributions in one of four fields: agriculture, viticulture, culinary arts or literature.

The recognition, impressive as it is, is just the tip of the iceberg. The real excitement comes at the lavish awards dinner prepared each fall by a rotating group of top chefs. Guests are treated to platters of delectable dishes, from smoked ham hocks to rosemary salt-cured beef tongue, from smoked sablefish to spit-roasted rabbit, the recipes inspired by Pellegrini’s books. With such an amazing line-up of dishes, it’s no wonder that tickets to the $150-a-plate dinner sell out in just days.

The award is administered by the nonprofit Pellegrini Foundation, established to increase awareness of Angelo Pellegrini’s prodigious role in preserving traditional values and celebrating the good things in life: fine food, wine and community. “The dinner recalls the spirit of Angelo,” said Frank Isernio, the 2013 Pellegrini Award winner. “It’s about sharing the table with friends and family, food being the tie that binds us together.”

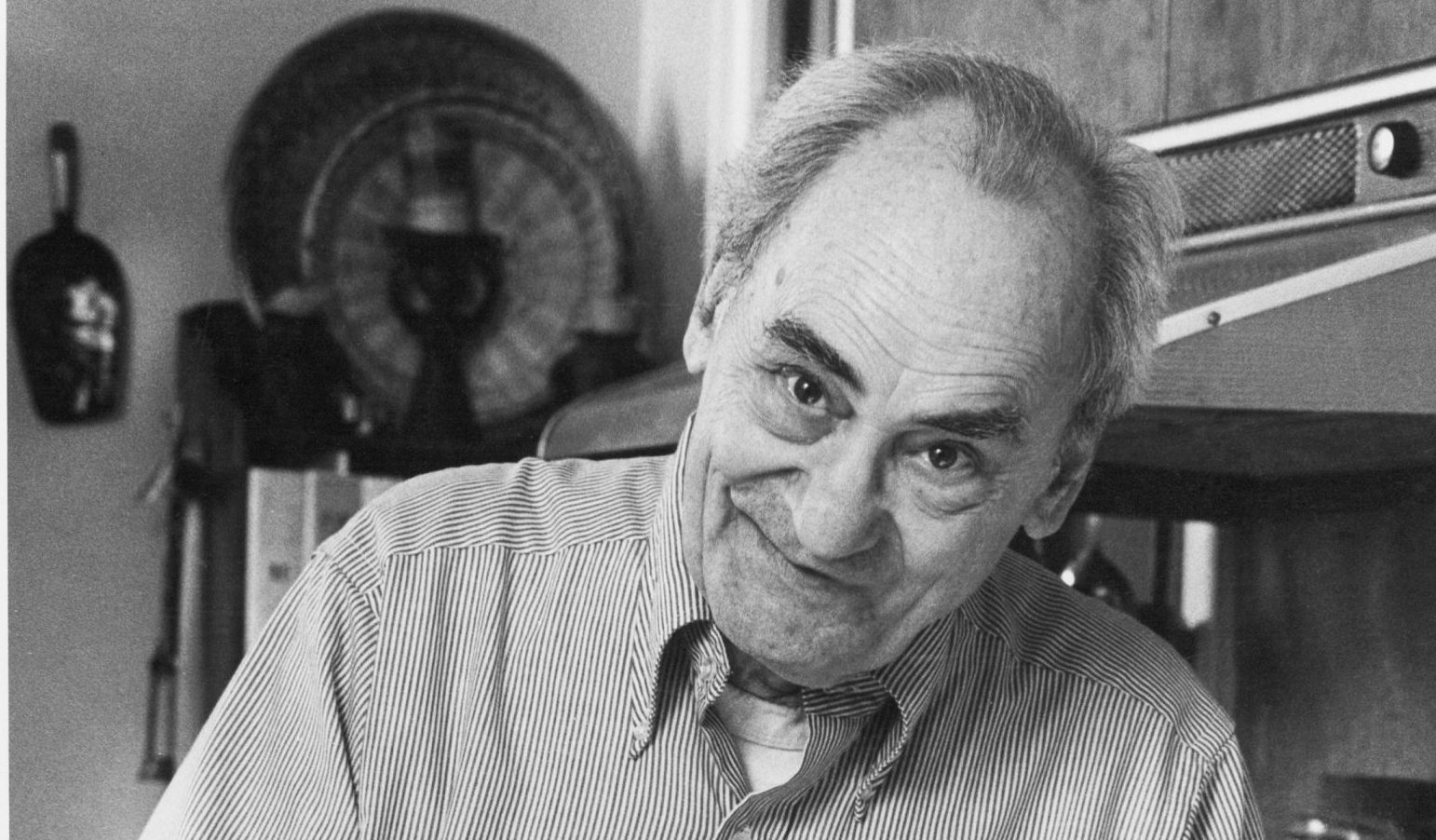

Known as Pelle to his friends, Pellegrini was proof that a lifetime of hard work, a healthy modest lifestyle, and a passion for family and communal celebrations can lead to amazing achievements. Born in 1903 in a village near Florence, Italy, Pellegrini arrived in the United States at the age of 10 with his mother and sisters. The family made their way to McCleary, Wash., just west of Olympia, to join his father who had settled there earlier. Unable to speak English, he was put into the first grade but he worked hard to catch up, studying long into the night.

Pellegrini excelled at school and went on to enroll at the University of Washington as a history major. He earned undergraduate and graduate degrees, with honors, and finished two years of law school before being hired by Whitman College as an English teacher. Years later, he returned to the UW as a professor of English and earned his doctoral degree. He was a spellbinding lecturer and became one of the most popular teachers on campus.

Despite his extraordinary academic career, Pellegrini was more renowned for his garden, kitchen and wine cellar. He made dough from scratch and baked bread in an outdoor oven he built himself. He gathered his own mushrooms in the forests, and grew all kinds of organic vegetables in a home garden so lush that Sunset Magazine once assigned a photographer to capture it on film over the course of a year.

In 1946, Sunset published Pellegrini’s recipe for pesto, reputed to be the first pesto recipe ever published in the United States. His first book, “The Unprejudiced Palate,” published two years later, is hailed today as a classic. Nine more books followed, including “Americans by Choice,” “Wine and the Good Life,” “The Food-Lover’s Garden” and “American Dream: An Immigrant’s Quest.”

On the surface, his books are about food and culture, but they delve deeper into questions that were close to his heart: what does it mean to be Italian, how do we maintain connections with others, what is a life well-lived?

Over the years, Pellegrini made friends from all walks of life. The writer Henry Miller was a fan, as were chef Alice Waters and food writer Paula Wolfert. The Mondavi family sent him a ton of grapes each fall which he turned into wine, giving most of it away.

Isernio met Pellegrini at a dinner years ago when Pellegrini was a keynote speaker. “He could really captivate a crowd,” recalled Isernio. “I introduced myself at the event, and after some conversation, Pelle invited me to his house to have dinner with his family. ‘I’m going to cook for you,’ he said. And he did. It was peasant food, but it was real cuisine. That started the beginning of a long friendship.”

As America embraced fast food, Pellegrini moved in the opposite direction, promoting local healthy ingredients, picked and eaten at their peak, simple and uncomplicated. “Today, everyone has heard about the slow food movement,” said Isernio, “but Angelo was espousing slow food 40 years ago. He had an unbridled passion for food.”

Food author and critic Ruth Reichl agreed, calling Pellegrini a slow-food voice in a fast-food nation. “Pellegrini believed that Americans would be the best cooks in the world if they only paid attention to the abundance all around them,” wrote Reichl. “He not only predicted the changes that would come, he helped make them happen.”