“If Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter,” said the French philosopher Blaise Pascal, “the whole face of the earth would have been different.” The same thought struck me at a reception held for the young Egyptian queen in November 46 BC at Julius Caesar’s villa on Rome’s Quirinal Hill.

Everyone admired Cleopatra’s nose. Long and curved like the prow of a warship, it was bound to attract Caesar, nearly as good an admiral as he was a general. If she had been snub-nosed like her youngest brother and puppet co-ruler Ptolemy XIV, Caesar, whose aquiline profile was stamped on every silver denarius, would never have made her his consort in Alexandria. Neither would he have shown off her marble bust to appreciative guests here in Rome.

“A peninsula worthy of conquest!” Caesar said, kissing the tip of the statue’s nose. Cleopatra, only twenty-two years old, could not refrain from nuzzling him. Even Cicero, whose bulbous nose was dented at the end like the cleft of a chickpea, laughed and applauded.

Romans history is a parade of noses. Scipio Nasica, the consul who enshrined the statue of Magna Mater on the Palatine Hill, was named after his enormous schnoz. So was the poet Ovid, surnamed Naso, who forlornly blew his exiled honker on the shores of the Black Sea. Sulla, the dictator who suffered from rhinophyma, executed anyone foolish enough to mock his proboscis, which resembled a mulberry encrusted with oatmeal.

Roman noses are still displayed all over the city, from the head of the shattered Colossus of Constantine in the Courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori to the billboard for Lady Gaga’s latest Europride Concert at the Circus Maximus. But the largest collection of illustrious noses can be found in the Pincian Gardens, overlooking the Piazza del Popolo. Let me show you.

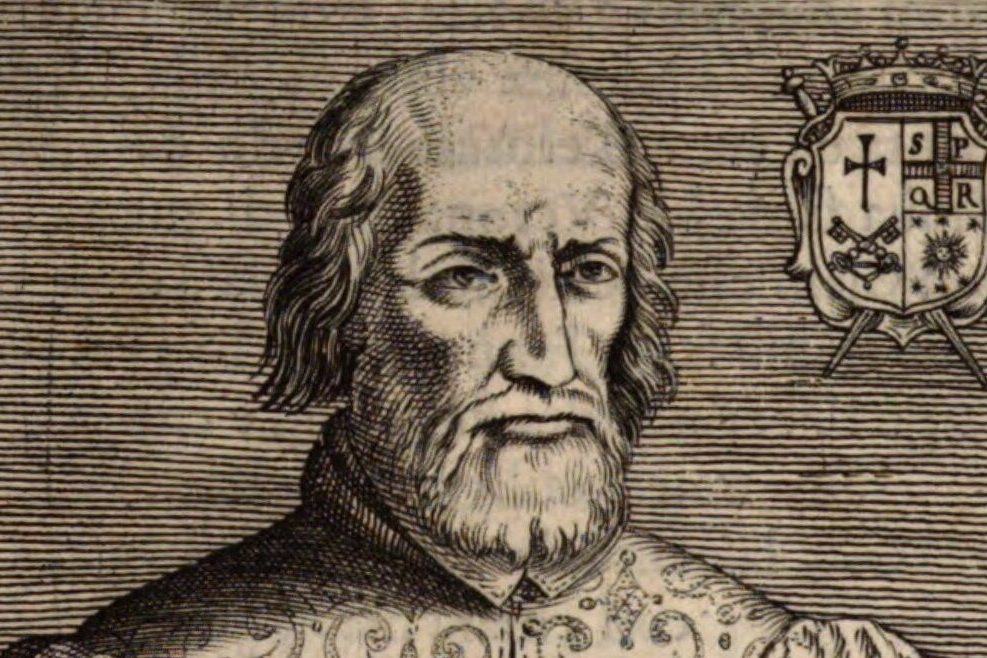

Laid out by Giuseppe Valadier during the Napoleonic Wars, the Pincian Gardens are Rome’s oldest public park and its Hall of Fame. Marble busts line its shady paths and the bridge connecting the gardens to Villa Borghese. Not part of Valadier’s original design, these busts feature monarchs and statesmen, painters and sculptors, scientists and inventors, poets and novelists, historians and philosophers, but no popes or cardinals.

After the Roman Republic overthrew Pope Pius IX in February 1849, Giuseppe Mazzini, eager to inspire patriotism, commissioned unemployed sculptors to carve 54 busts of famous Italians for the Pincian Gardens. Four months later, when the papal government was restored, only the busts of the most uncontroversial figures were set into place. The busts of secularists, heretics, and revolutionaries were removed and stored in Casina Valadier, the park’s neoclassical villa.

Eventually, these busts were returned outdoors, but not before receiving drastic makeovers. Giacomo Leopardi, the nihilistic poet, became the Greek painter Zeuxis. Niccolò Machiavelli, the anticlerical political scientist, was turned into the mathematician Archimedes. Girolamo Savonarola, the radical Dominican friar, was recast as Guido of Arezzo, the Benedictine monk who invented musical notation.

After the Papal States fell in 1870, these and other historical figures altered for political reasons finally received recognition. New busts of them were carved and set side by side with the older ones already in the Pincian Gardens. Over the next ninety years, busts of other famous Italians were added to the pantheon until the total number reached 228.

As you see, they are a snooty bunch. Their upturned noses, whose blanched marble stands out in stark relief against the park’s evergreens and palms, are often smashed or docked. The vandals include disgruntled art critics, who consider the statues Risorgimento kitsch; angry feminists, who resent that only three women (Catherine of Siena, Vittoria Colonna, and Grazia Deledda) are among the immortals; spiteful anarchists, who hate all governments; and selfish tourists, who want souvenirs.

Ten to twenty busts are defaced each month, so the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities keeps an expert restorer on the payroll and a depository of casts of the Pincian’s illustrious noses: hooked noses and cocked noses, sharp noses and flat noses, round noses and square noses, pinched noses and wide noses. Each nose job, City Hall estimates, costs 800 euros (about $900). This expense drains funds from other restoration projects.

Since I am a noseless statue, whose features have been eroded by time, I could complain. But all things, whether stone or flesh, are subject to the cruelty of fortune and the absurdity of politics. No one is exempt, not even the Queen of Egypt, whose mutilated bust is relegated to a corner of the Museo Greogoriano Profano at the Vatican.

After Julius Caesar’s assassination in March 44 BC, conspirators broke into Caesar’s villa and snapped the nose off Cleopatra’s bust, but the lady herself had long fled. Thirteen years later, when her new lover Mark Antony angrily recalled this outrage, Cleopatra shrugged and smiled.

“What do you expect?” she asked. “Eternal glory?” She shook her head and sighed, thinking of the coming Battle of Actium, which she and Antony would lose. “When the great die,” she said, “they don’t go to Elysium but to Rhinokoloura.”

The allusion, I’m told, perplexed Antony, a hunk with a chiseled nose but no genius like Caesar, so Cleopatra explained. Rhinokoloura was a place of banishment in the Sinai desert for criminals whose noses had been sliced off.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.