During a recent visit to the Museo Teatrale della Scala I admired many antique prints of commedia dell’arte situations. Commedia dell’arte was a theatrical genre that evolved in the latter part of the sixteenth century. It was a popular reaction to the erudite, dramatic traditions of the beginning of the century attempting to rival the great drama of antiquity. It was not a written art form, rather, it was based on the improvisation by the actors who worked around a canovaccio (literally canvas), or a brief sketch of a plot. During the latter part of the sixteenth century, groups of actors formed troupes (called compagnie) and traveled playing this type of unwritten dramatic form in inns, market places and theaters. They traveled in Italy, in France and all over Europe, influencing the theatrical traditions of the countries they touched. Since plays were not written down, we unfortunately do not know exactly what a commedia dell’arte would have been like. We have, however, a number of scenarios left to us. The most important collection was published by Impresario Flaminio Scala in 1611.

The commedia dell’arte developed types, also called maschere, or masks, for different stock characters. These types were regional, wore a typical costume and spoke the dialect of their region. Among these characters, the lovers, the inamorata and the inamorato, had a special place. Often, the improvised play would spin around their peripeties as they were.

Like Romeo and Juliet, by the inimical will of their parents. Only, since we were in the realm of comedy, a happy ending was assured! The lovers did not wear a mask and their speech was lofty and romantic. They provided a semi-tragic quality to the action with their love troubles. We must point out that, unlike in Elizabethan theater, women actually played women’s roles on the Italian stage.

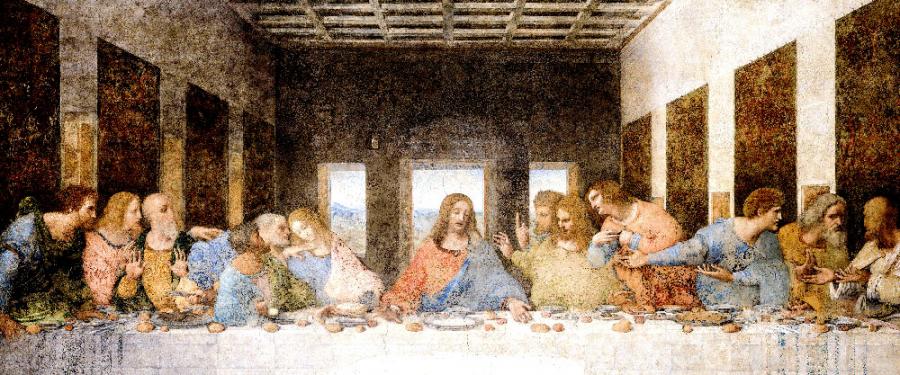

The classical appearance of the Harlequin stock character in the commedia dell’arte of the 1670s. (Maurice Sand, 1860)

The comic characters were called maschere because on the scene they wore masks to have a stylized effect. The romantic plot was reinforced with iazzi, that is, improvisations of a bawdy or slapstick nature. The zanni (this name comes from Giovanni, Zuanni, in Veneto dialect) were comic characters that gave the word “zany” to the English language. The scenario would change, but the types remained the same, giving the public a sense of familiarity with the dramatic action. There was no need to explain what each type or actor would do: the audience knew ahead of time. Among the numerous masks, the most famous are: Arlecchino, Pantalone, Brighella, Pulcinella and the Captain. We do not know where Arlecchino got his name.

Famous for his patchwork costume made of diamond-shaped lozenges of all colors, he was a devious and naughty servant. He was a mixture of cunning and grace and spoke in the dialect of Bergamo in Lombardia. The actor who played Arlecchino has to be very acrobatic and be able to jump, scale, walk on stilts, somersault, and walk on his hands.

Brighella was Pantalone’s servant and worked to undermine his padrone at every turn. He wore a white livery with green stripes. His name comes from the word briga, denoting an imbroglio, a mess. He was a troublemaker. Abroad, the name of Pulcinella evolved into Punch. His name means literally little chick, and may have been inspired by the clucking sounds he made. Pulcinella was hunchback with a hooknose, traditionally dressed with a flowing chemise tied with a rope around his waist. He wore a short black mask and the typical sugar loaf hat. He was intelligent, funny, human, a spaghetti-eating Neapolitan master of intrigue.

The mask of Pantalone is Venetian. His name appears to have come from Pantaleone, a saint patron of Venice. Pantalone de’ bisognosi, as he was called, Pantalone of the Needy, because he was very stingy. He was old, rich, a doctor by profession, and always unsuitably in love with a young woman. The Captain was always present. In those days of Spanish domination, the bragging Spanish Captain was a way for Italians to make fun of the invaders and to vent their anger against the over-powering military men invading them. The Captain would have like Capitan Spavento (terror) or Capitan Terremoto (earthquake) or Matamoro (killer of Moors) or Spaccamonti (mountain-splitter). He would speak a funny mixture of Spanish and Italian. He would strut about and spin endless tales of military prowess and amorous conquests. The dramatic action would in the end show him for the contemptible coward he was.

With me, more and more minor comic masks developed, some created by famous actors themselves- masks having bizarre or ridiculous names: Franca Trippa, Fritellino, Pedrolino (from whom came the French Pierrot), Mezzettino, Carlin, Pasquariello, and many others. Il Dottore was a mock doctor, most of the time pedantic. We also had the bespectacled Tartaglia (the Neapolitan lawyer who stuttered), Coviello, and Scapino, a type that Molière immortalized in his theater.

The most prominent actress of commedia dell’arte was Isabella Andreini, married to Francesco Andreini. She belonged first, then managed, with her husband, the troupe of the Gelosi. She created her own mask, Isabella, a beautiful heroine always about to go crazy because her parents would not let her marry her beloved. Her husband, Francesco Andreini, became very famous playing Capitan Spavento (Captain Terror).

Commedia dell’arte is not dead. We see dramatic action with roots in this genre on the stage even today. We also see residues of commedia dell’arte in the television show “Whose line is it anyway”, showing that improvisation and slapstick are still very popular with the public.