On Monday, schools reopened in twelve regions of Italy, more than six months after the bell rang for the last time in March. It’s been an important moment for the almost nine million students who finally, rucksack in hand and homework completed, managed to meet their peers and teachers again: so many things have changed in the world since the last time they sat there, at their desks, changes they — and we —may not even fully comprehend just yet.

Il primo giorno di scuola has never been so profoundly symbolic of a moment of rebirth and “ripartenza,” of starting over again, a word we learned to love in the past months, as busy as we’ve been trying to lift spirit and economy from the fear, tragedy and psychological shock of the pandemic; pandemic that is still here and still scares us, but that we’ve learned to handle and to fight more efficiently, while waiting for a vaccine.

Ripartenza, indeed, as symbolized powerfully by the presence of Sergio Mattarella, the President of the Italian Republic, at Vo’ Euganeo on Monday to celebrate the beginning of the school year just there, where the first Covid-19 red zone of Europe was created in the late days of February.

But in the context of school and education, ripartenza does not only mean getting back to class, but also doing it placing learners at the heart of the process, and not only because they need to catch up on the curriculum after a school year almost entirely spent online. Students need to go back at the heart of the teaching-learning process because the future is theirs, because their minds, if properly nurtured, will be the ones protecting humanity from another tragedy like that of Covid-19 happening.

It is in this context of the didactic centrality of the child and the student that Maria Montessori, whose 150th birthday was celebrated a handful of weeks ago, takes powerfully center stage: as an educator, of course, but also as a woman of science in times when it was even more difficult to become one, and as a profound estimator of the importance of technology in a pedagogical context, an aspect that has been stressed a lot during the lockdown months when distance learning was the norm, but that remains important now, as it will still be used through the school year. But the importance of technology in Italian schools goes beyond distance learning today: IT is taught to children and is then used at later educational stages as a support both in class and at home. Scientific subjects, or STEM subjects, have also gained popularity, essential as they are to prepare the citizens of the future to a professional world that is bound to be increasingly based on them. And we could go on, talking about how robotics are used didactically and how simple coding became part of the curriculum in many elementary schools, all to underline the relevance of technology, but also Montessori’s insight in understanding it already more than century ago.

Indeed, her whole life was to develop along the technological and scientific ways of human knowledge. And to fulfill her dream, Maria Montessori had chosen the Faculty of Engineering, accepting to move from the tranquillity of Chiaravalle, in the Marche region, to the bustling and lively reality of Rome, capital of the Kingdom of Italy.

She was born in 1870, daughter of Alessandro and Renide Stoppani, both of them active in politics. Maria was an only child and, thanks to a liberal and tolerant family environment, she soon developed the roots of that altruism and interest in others that were to characterize her. In 1875, she enrolled in a Roman public primary school, and then continued her studies in a technical and scientific institution, where she obtained her high school diploma: by then, she had clear ideas and a fearless attitude.

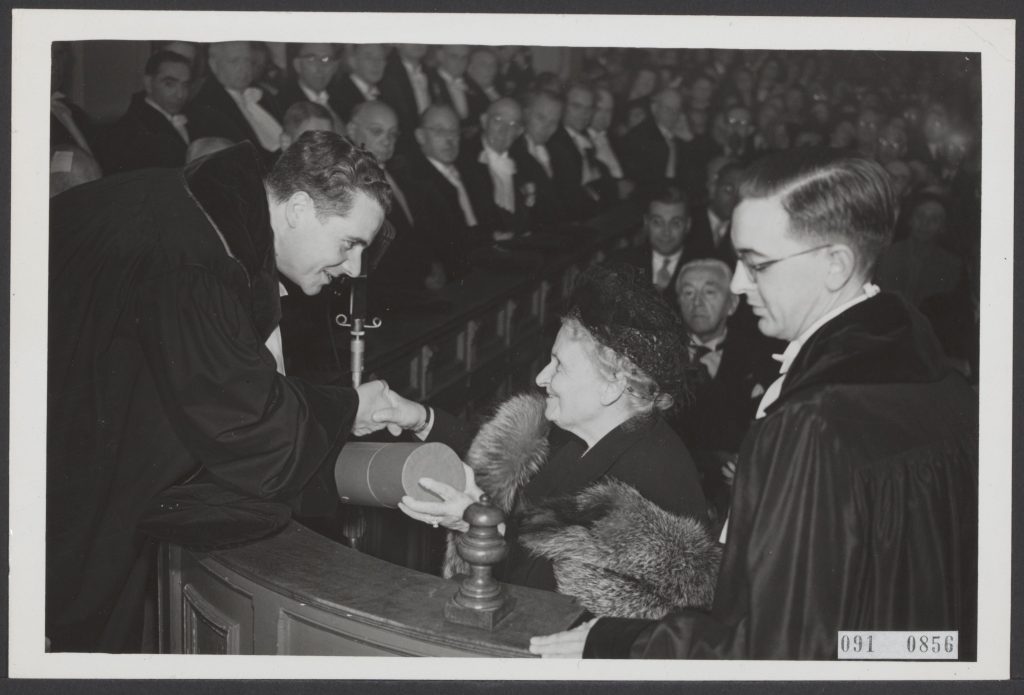

But there wasn’t much space for fearless, resourceful women, in those last years of the Italian 1800s, especially for a woman who wanted to become an engineer: Maria had to fall back on medicine, transferring on anatomy and physiology her passion for technology. Along the way, the young student discovered a third way, one that with time was to bear the richest fruits for her. She decided to become a psychiatrist and to prepare her thesis on the subject of human mind. She graduated in 1896, among the first women in Italy and, after four years, she was offered her first job at the Santa Maria della Pietà mental asylum. It was a terrible experience, spent among the most unfortunate, which touched the young doctor immensely. It was the presence of children, often suffering simply from behavioral issues, to upset her the most: abandoned to themselves, they were treated like adults, that is, just a little better than animals. Maria’s professional interest grew and she decided to dedicate to them her mission. Resolute and energetic, she dedicated herself fully to the care of her young patients and with the help of the right equipment she obtained unexpected results. With great excitement, the doctor began then her personal battle in support of disadvantaged children, championing for their rights at all the early 20th century medical congresses she attended. At the same time, Montessori began working with healthy children, with the aim of making a difference in the way Italian schools were organized. Once she obtained the position of professor of pedagogical anthropology, the young doctor decided to implement her didactic method in a private school.

And this is how the 6th of January 1907 became such an important day for the children of the world. It was on that day Maria Montessori opened her Casa dei Bambini (the children’s home) in San Lorenzo, one of Rome’s poorest boroughs, for children aged 3 to 6. The school was located in a large working class building at 58, Via dei Marsi: here, Montessori could observe and understand better the “unsuspected psychological characteristics” of children who were no longer oppressed nor demeaned. The Casa dei Bambini became an attraction of the capital and many visited it to learn from the children themselves that no award nor punishment could balance out the happiness given by being industrious.

In just a handful of years, more and more case appeared and Montessori’s name became famous. Her method induced positive behavioral changes in children and allowed adults to discover they had a much deeper respect for things and other people than it was believed. After a Casa dei Bambini opened in Milan, Montessori’s writings began circulating outside of Italy. Dr Montessori’s Own Book and The Advanced Montessori Method were discovered with much clamor in the US, revealing an approach that not even the modern New World had managed to conceive. And so American children, just like their Italian friends, could rise to a higher level of consideration, both from a psychological and emotional point of view.

In 1913, in Umbria, the first Montessori method course for teachers was inaugurated. In later years, more and more American teachers enrolled, which made the thought and work of the Italian psychiatrist more and more famous across the ocean. The enthusiasm for the Montessori method became huge: everywhere, thanks to the creation of a special environment and specific objects to work with, the miracle of concentration, individual peace, high standards of socialization and exchange kept on repeating itself over and over again. Maria Montessori had “freed” children from the yoke of old fashioned education.

Her greatest intuition was that of applying pedagogical principles commonly used for children with psychiatric issues to all children. Indeed, it was her opinion that children with handicaps could truly benefit from the right type of education, often more than from medical treatment. Traditional pedagogical methods were irrational because they repressed children’s potential instead of nurturing it and supporting its development. Sensory education became a preparatory moment to cognitive development because a child’s education, just like that of a differently able person, needed to focus on sensitivity, something everyone, regardless to their mental and physical abilities, had.

The Montessori method taught how to educate children to self correct their mistakes, as well as looking for mistakes even without the teacher’s intervention. The child was free to choose the materials for exercise, thus enhancing the role of personal interests and inclinations and developing his or her self-education and self-control skills. The success of this educational method continued. Her method allowed children to become responsible, to take into their hands the learning process, under the protective and knowledgeable wing of their teachers, a bit like it happened to our children during the pandemic: unable to be in school, they adapted to a new way of learning, they understood how to assess their performance and learned not to fear questioning and asking for clarification. In many a way, every child in Italy, during the lockdown, became a little Montessori learner, who gained a deeper understanding of his or her possibilities and weaknesses.

In 1922, Montessori was nominated Kingdom of Italy’s school inspector: she became a tireless traveler. With every journey, new Montessori schools opened and she often visited the United States. She was also welcomed with great honors to the White House, special guest of Margaret, the daughter of President Woodrow Wilson. The Montessori Educational Association was enthusiastically sponsored by figures of the caliber of Alexander Graham Bell, further confirmation of a method that was to produce, through the years, more that 5000 private and 200 public schools, along with large numbers of specialized institutions where teachers who wanted to dedicate their career to the method could train.

But it wasn’t all a bed of roses for this exceptional pedagogue.

Montessori schools, as it may easily be understood, were opposed by all totalitarian regimes, so they were closed during the dark years of the Second World War in countries like Italy, Russia, Germany and Spain. Montessori herself was forced to leave Italy and move to Barcelona first (1934) and, after the Spanish Civil War, to the Netherlands. In 1940, she was imprisoned in a German concentration camp; freed thanks to political negotiations, she was nevertheless forced to leave the Old World and moved to India. Far from feeling dejected, Montessori opened her first school in Asia in Adyar shortly after. She was back to Europe in 1947 and settled in the Dutch town of Nordwijk aan Zee, where she died on the 6th of May 1952.

Her death was not to turn into ashes all her activism. Great names of world pedagogy studied at her school, including Anna Freud, Jean Piaget, Alfred Adler, Erik Erikson. Among her many books, The Secret of Childhood, The Formation of Man and the Absorbent Mind remain key texts for the formation of all pedagogues.

Her personality was not as clear cut and easy to define: neither fully laical nor only a Catholic, Montessori was first courted by the Fascist regime, then opposed by it. She became a member of the Theosophic Society, which was created in the US, and was almost considered a guru of childhood education. Once she returned to Italy after the end of the Second World War, she was acclaimed by the Italian Parliament. Her answer to all that clamor was typical of her exceptionality: “I’m showing you children, their inner wealth and you just cannot see it. You’d rather look at my finger while it points at them, stare at it, repeating how beautiful it looks…”

Celebrating the birthday and, most importantly, the pedagogical genius of Montessori is even more important today, after the year we’ve been experiencing so far. We understood how, without schools, the very glue that keeps together our society, families, habits gets thin. We understood that, without learning, children are more afraid, that knowledge, even the basic knowledge given to the younger of kids, can be a powerful and positive weapon against fear.

We understood that children are resilient, that they can be responsible and that they should be put in a position of responsibility, also and especially when it comes to their education, because they can handle it, just like Montessori stressed. And we understood that, just like the pedagogue anticipated, everything is an instrument for learning, when used appropriately: even our tablets, even our old computers, even the stress and fears of a pandemic.

Montessori, this year, is more relevant than ever: she reminds us, but in a positive manner, what the pandemic made clear: education and learning are the essence of humanity, only through them we can rise above infections, ignorance, intolerance and all the negative and all the darkness that permeates our world.