Everyone knows Mount Rushmore, with its iconic representations of four of the most important presidents of US history: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, F.D. Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. As a child, I remember being fascinated by their stoney, gigantic faces and I often wondered how someone could have made them look so perfect and lifelike; as you would expect from a 5 year old, I thought a single sculptor spent his entire life carving the mountain on his own, with his scalpel in one hand and a hammer in the other, failing to understand that a project of such a magnitude had very likely involved hundreds of people through a number of years.

Even if I had known that then, I certainly would not have been aware of the essential role of Italy in the creation of the Mount Rushmore Memorial, because its recognition came only in very recent times, when a previously unknown Friuli Venezia-Giulia migrant, Luigi del Bianco, was recognised as chief carver of the monument.

Bringing justice to Luigi

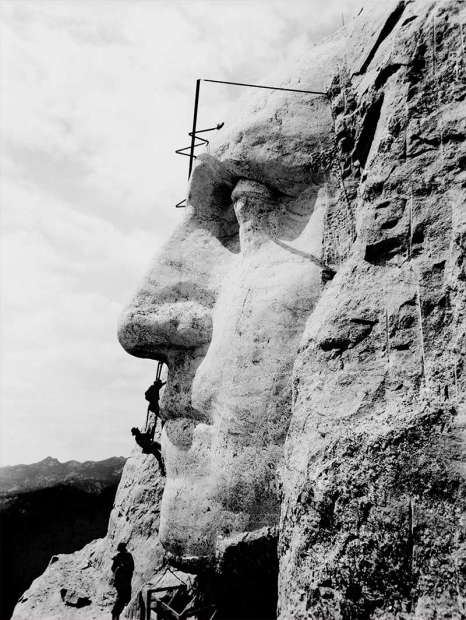

History tells us that, between the 4th of October 1927 and the 31st of October 1941, 400 people worked on the sculpting and carving of Mount Rushmore. They were led by Gutzon Borglum and his son, sculptors and artists of Danish descent.

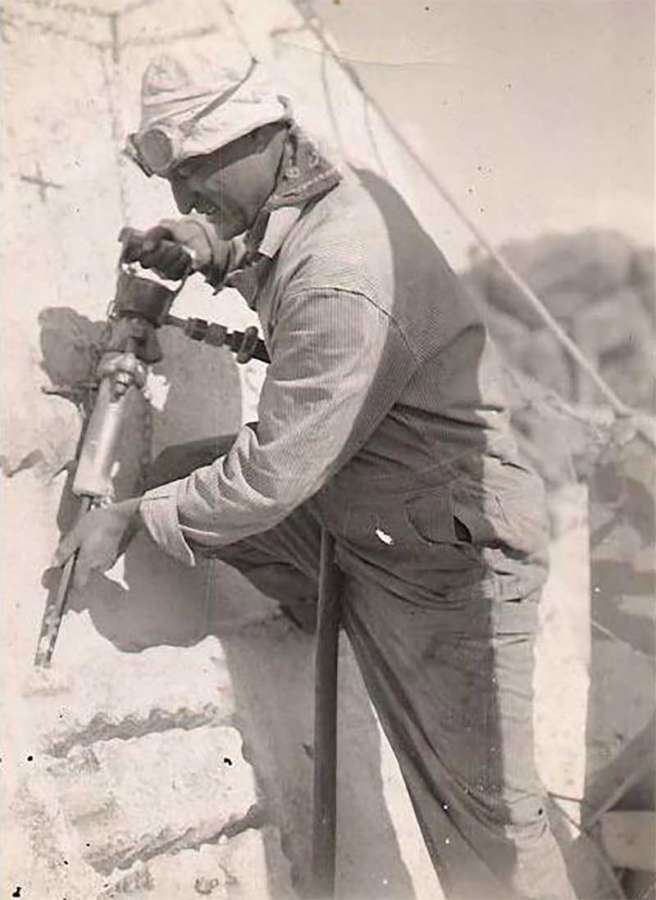

Among those 400 workers, in 1935 made his appearance Luigi del Bianco, from Meduno, in the north eastern region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, who had studied carving in Venice and Vienna before trying his luck on the other side of the ocean and emigrating to the United States. Del Bianco’s name became known among historians and specialists of Mount Rushmore when his own grandson, Lou del Bianco, and his late uncle Caesar, began a strenuous campaign to have the role of their own ancestor in the making of the Mount Rushmore Memorial recognised.

Because Caesar and Lou both believed Luigi had been more than a simple worker at the site, they set on a quest: demonstrating it to the world. It was Caesar, son of Luigi, who started the amazing adventure in the late 1980s, when Rex Allen Smith published “The Carving of Mount Rushmore:” here, the name of his father never appeared. Caesar was gutted.

More than 20 years later D.J. Gladstone, the author of the ultimate work on del Bianco, “Carving a Niche for Himself” (2014), would say that talking about Mount Rushmore without mentioning Luigi del Bianco was the equivalent of talking about the Yankees without mentioning Joe DiMaggio: but how much research, work and perseverance was behind such a statement. The research, work and perseverance of Caesar and his nephew Lou, who explored libraries, unearthed documents and campaigned for recognition, refusing to let their relative fall into oblivion.

After Caesar’s death in 2009, Lou took up his mission in full and it’s also thanks to his relentless efforts that Cameron Sholly, current director of the Midwest region for the National Park Services, accepted to reassess Luigi del Bianco’s role in the inception and creation of Mount Rushmore. Shelley came to the conclusion that del Bianco’s grandson was right: Luigi had been, indeed, the main carver at the site, the artist who gave to America’s timeless stone presidents their life-like features and immortal gaze.

Who was Luigi del Bianco?

Chief carver at Mount Rushmore, of course, but his life held much more than that. He was born in 1892 aboard a ship near Le Havre, in France, while his parents had been returning to Italy from the United States. The family, as said, settled in the North East of Italy and it’s there that 11 year old Luigi started studying carving and understood how talented he was. Still an adolescent, he had travelled to the US for the first time and settled with relatives in Vermont: there, he became known as a skilful carver. After returning to Italy to serve his country during the First World War, he was in Vermont once more and then settled in Port Chester, where his family still resides today.

While in Port Chester, del Bianco met Borglum, with whom he began to work: it was the beginning of the collaboration who was to bring him to South Dakota and to Mount Rushmore where, as chief carver, he became responsible of refining the presidents’ facial expressions. According to The Times, he spent a particularly long time sculpting Lincoln’s face and his eyes, whose pupils were made more vibrant by inserting wedges of granite in them. He worked at Mount Rushmore from 1935 to 1941, when he returned to Port Chester. Here he died in 1969, at the age of 78, because of silicosis, a disease caused, tragically, by the same thing that gave him so much joy in life: stone.