Over two thousand named characters, action which spreads across the earth and even to the moon, female warriors, monsters, magic, three main plots, numerous sub-plots, and witty asides by the author all woven together into a veritable “page turner” make Orlando Furioso into what such diverse critics as Voltaire and Sir Walter Scott considered the greatest of all epics.

It influenced generations of later writers such as Scott, Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser, Cervantes, Jack London and Salman Rushdie, artists like Tiepolo and Ingres, opera composers including Vivaldi, Handel and Haydn, science fiction, fantasy movies and even video games. In Sicily the entire work is performed by marionettes, which have been designated by the European Union as a major art form.

Yet, despite the greatness of the work in itself, to say nothing of its important influence, it is the rare world literature course that even has an excerpt from it, and rarer still to meet an American who has read it; the ultimate insult is that there is no Cliff Notes version!

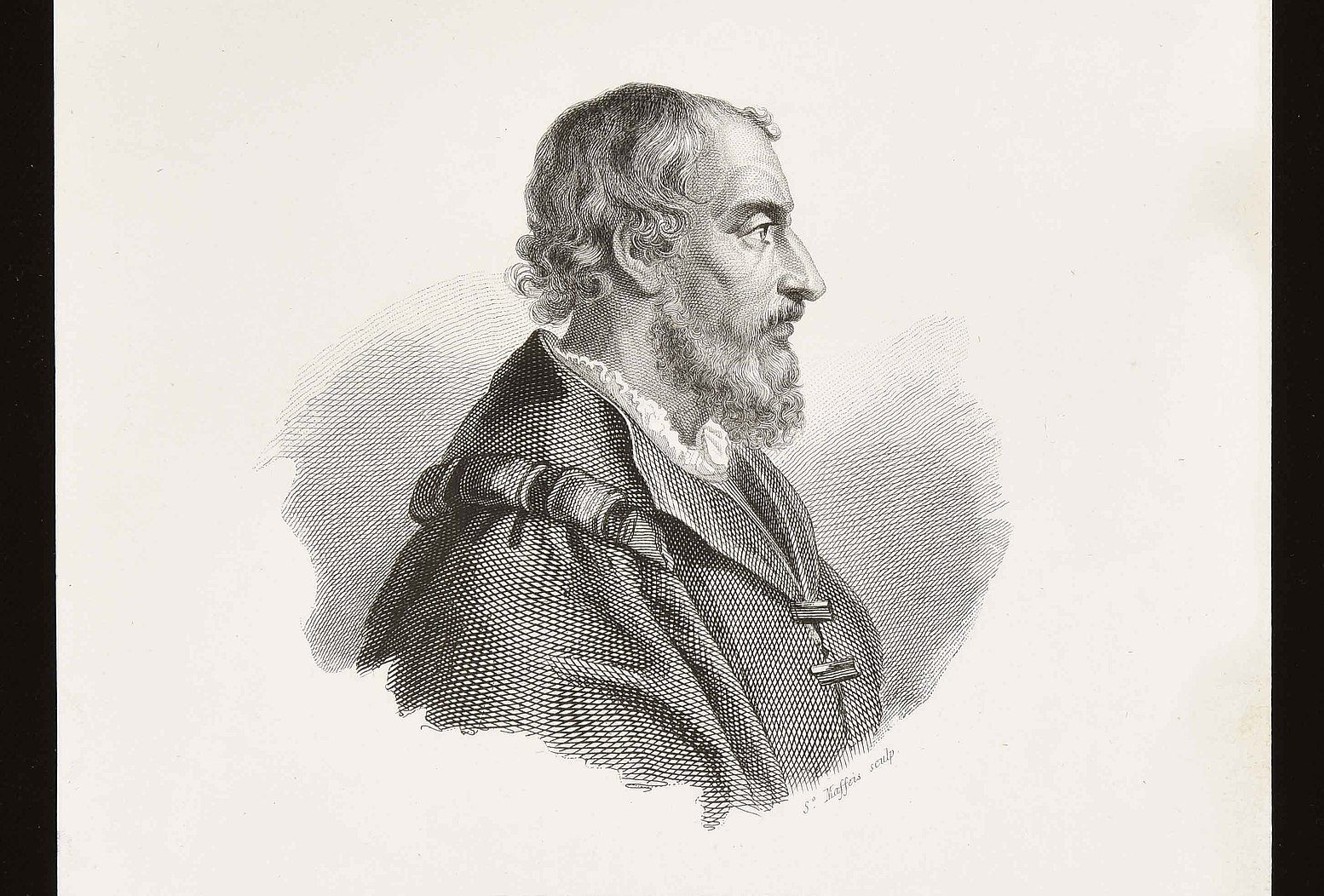

Ludovico Ariosto was born in Reggio Emilia in 1474 into the noble family of Niccolò and his wife Daria (Malaguzzi). A precocious child, he displayed an early interest in literature and wrote and acted in a poetic play when only nine. Despite this juvenile display of talent his father wished him to pursue a legal career and thus at the age of 15 he began five years of the study of law at Ferrara. Having placated his father, he was able to return to his true love and mastered the Greek and Latin classics.

Fortune intervened in 1500 with the death of his father. Being the eldest of ten children he had to forgo his literary pursuits to become head of the family. After settling their affairs he had to seek employment, first as commander of a fortress at Canosa, and in 1503 became a courtier to the Duke’s son, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este. Italy at this time was in a state of almost constant warfare and Ariosto served as a diplomat, occasionally as a de facto butler, and accompanied the Cardinal and the latter’s brother Alfonso on military expeditions.

On one he narrowly escaped with his life while they were being pursued by Pope Julius’s men. Despite all this activity, he still found time for writing, composing poems in Italian and Latin, dramas, and in 1505 began his greatest masterpiece, Orlando Furioso, which he finished and published a first edition of in 1516, dedicated to the Cardinal, who was ungrateful for the honor.

Thus, in 1517 when he became Bishop of Buda in Hungary Ariosto declined to accompany him and went into the service of Alfonso, who was Duke of Ferrara. A few years later he became governor of Garfagnana in northern Tuscany, a wild mountain region plagued by feuds among the powerful local families and overrun by bandits. Despite having almost no support from the Duke he managed to settle things among the warring factions and curb the robbers.

Even with all this going on he still found time to write, producing poems, satires and plays, as well as working on a second edition of Orlando Furioso published in 1521, which he still continued to work on afterwards.

In 1525 his finances were secure enough for him to retire from his political career. He purchased a pleasant house with a garden in Ferrara, was able to secretly marry his mistress, Alessandra Benucci, and devoted himself to literature, publishing the third edition of his great epic in 1532. He died the following year.

From its first appearance in 1516 Orlando Furioso was acknowledged as a masterpiece and was eventually translated into every major European language; Queen Elizabeth herself commissioned the first English edition. Being one of the longest poems in any language, it is impossible to do it justice here.

Briefly, it involves the struggle between Charlemagne and the invading Saracens, the temporary madness of Orlando (Roland) over the loss of his love Angelica, hence the title, and the love and marriage of the female knight Bradimante and Ruggiero, the supposed founders of the d’Este family, all interspersed with swashbuckling adventures. Equally amazing, it was written in ottava rima, a complex rhyme scheme of abababcc, which is virtually impossible in any language but Italian. Thus, Walter Scott taught himself it so he could read it in the original, something he did each year.

It is more than fitting that Ludovico Ariosto should hold a place of honor with the other great epic poets Homer, Virgil and Dante, which is where Raphael depicted them all in his Mount Parnassus. We should all honor his memory by reading his great poem, even if in translation.