This, more than any other before, is the year of Leonardo da Vinci, as we celebrate the 500th anniversary of his death, which took place in Amboise (France) on the 2nd of May 1519. Leonardo, then, was 67. He had left Italy some three years earlier, when his patron, Giuliano de Medici passed away, to serve as a confidant and intellectual guide for Francis I, king of France. Leonardo’s hands were crippled by age and wear and tear, so painting was out of the question, yet his enlightened mind was enough for French royalty to want him at court. Giorgio Vasari, author of the Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, wrote in 1550 that, in fact, Leonardo died in the king’s arms. A romantic depiction indeed, to the point it also inspired a famous painting by Auguste Dominique Ingres, some 300 years later.

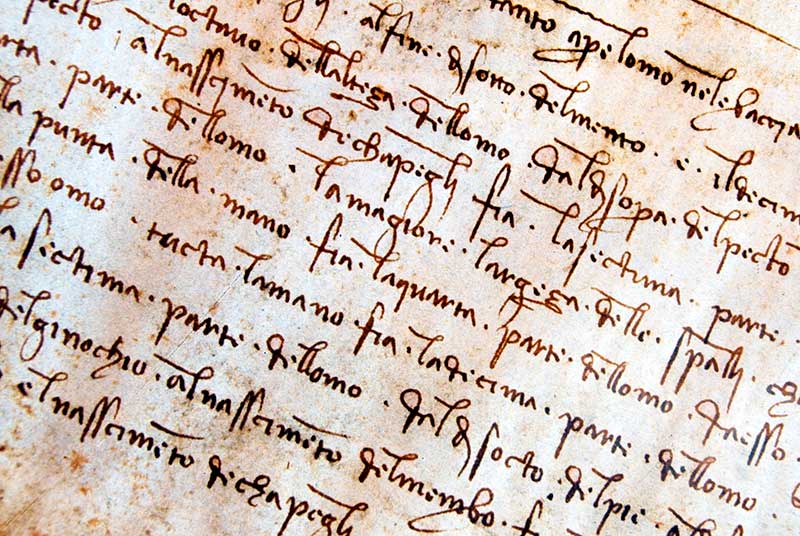

Leonardo’s writing: also known as mirror-writing, where the words appear as normal when seen with a mirror

Five hundred years without Leonardo, but doesn’t it seem like we actually all grew up with him as a mentor and a teacher? Of course: his name is ubiquitous in the arts and in science, his genial inspirations behind some of the world’s most important discoveries: the calculator, the helicopter, the bicycle. And what about the paintings? What about the Vitruvian Man and the Mona Lisa? Leonardo was, and still is, the ultimate trans- generational, or better, trans-epochal icon: from intellectuals to children from North to South and East to West, everyone knows his name and what he has done.

A self portrait of Leonardo

But in the year that celebrates the 500th anniversary of his departure from this world, we should really ask ourselves what we truly know about him, and what he really achieved for the development of our civilization.

The Last Supper is one of Leonardo’s most famous works, but it has been deteriorating easily, because it was painted on dry plaster, rather than using the usual fresco technique

Interesting questions, both requiring a bit of research and a certain amount of mental archaeology to find out what’s still in our heads after all these years without school. What’s curious about Leonardo is that, in fact, the world doesn’t know that much about him at all. We know where he was born – in Vinci, a small village near the Tuscan town of Empoli – and the name of his father, Ser Piero, a well known florentine notary with a penchant for beautiful women. And so, here comes the first thing about Leonardo we ignore: the origins of his mother. Her name was Caterina, she may have been a pauper, she may have been the daughter of a small landowner, she may even have been a converted slave: this last theory became fairly popular after a group of international researchers managed to isolate Leonardo’s fingerprint and recognized in it a pattern typical of Middle Eastern populations. They say they may be able to get his DNA and finally shed some light on the mystery. But how could they get Leonardo’ DNA, as we don’t even really know where his bones have been laid to rest? The Saint Florentin church of Amboise, where tradition wants his mortal remains to be, no longer exists: it was demolished in the yearly years of the 19th century. Sure, some bones were found and buried as his, but are they, really?

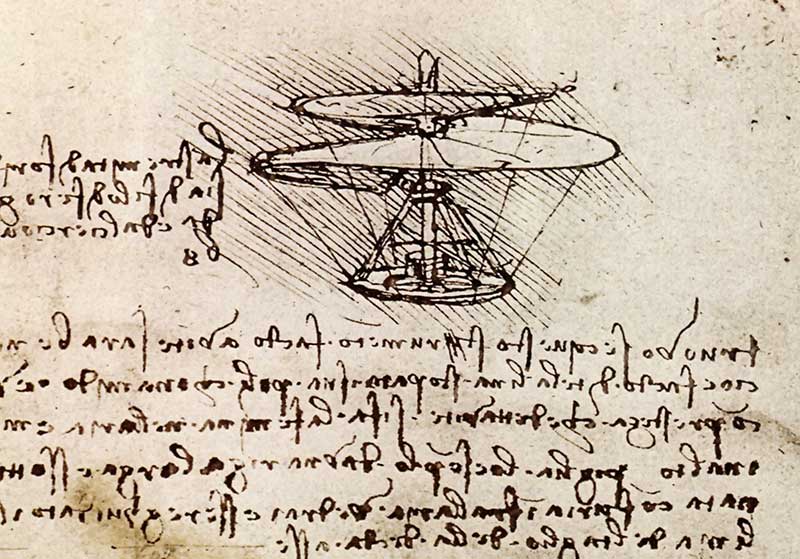

Leonardo’s flying machine: to the eyes of many, a very early ancestor of our helicopters

Leonardo, a true man of mystery. You wouldn’t expect anything less from the mind who protected for decades the most explosive secret of western civilization: yes, I am talking about the Priory of Sion, of course, central element of Dan Brown’s 2003’s best seller, The Da Vinci Code. But that, alas, is all an invention: there isn’t such a thing as the Priory of Sion, nor do we have any historical proof about his existence in the past.

What about his inventions and paintings, what can we really say about those?

It is not only Leonardo to be surrounded by mystery, but also his work: La Gioconda remains one of the most enigmatic paintings in the history of art

I recently read an interesting, albeit certainly controversial, post by a blogger quite aptly called Leonardo. Well, he maintained that, in the end, none of the inventions Leonardo da Vinci conceived all those centuries ago were realistic, otherwise they would have been made there and then. He was a visionary, for sure, but was he a true inventor? And when it came to art, he had the habit to leave works unfinished and to try unsuitable methods to paint, often resulting into the quick deterioration of his masterpieces: well, he did decide to paint the Last Supper on dry plaster instead of using the usual fresco method because he thought his pigments were enough to last in time, even on a dry piece of wall. And we all known he was sadly mistaken.

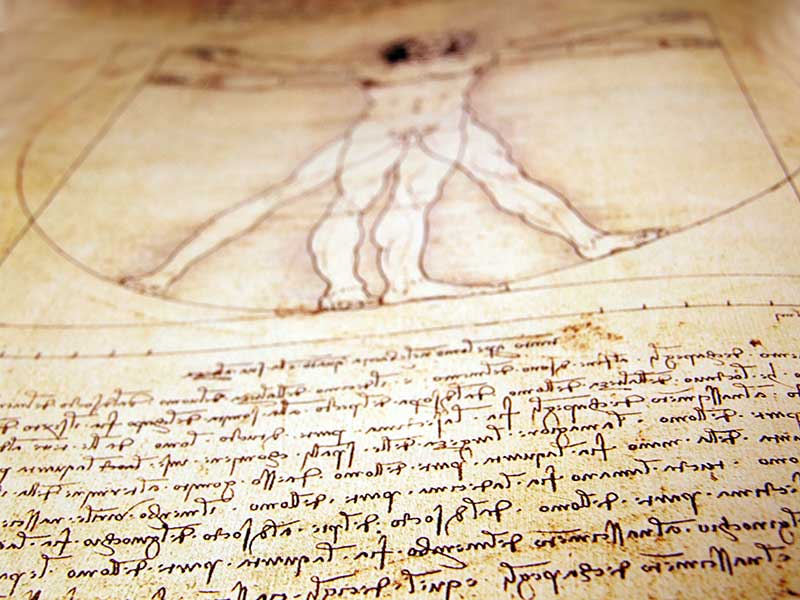

The Vitruvian Man, and an example of Leonardo Da Vinci writing: he used to write right to left and to read his notes, we should use a mirror

Yet I, and I believe all of you, draw the line here: dear blogger, thank you for giving us some uncommon views on old Leo, but let us politely disagree with you.

It is true: none of Leonardo’s inventions were actually made in his own lifetime. But what about the geniality of his intuitions, which he had, by the way, some 3-400 years before anyone else even tried to come up with similar ideas? And yes: he was inconsistent and moody when it came to his artistic work, but which artist isn’t, in the end? Isn’t it that the ultimate symbol of creative genius, so much so in Italy we even say it, genio e sregolatezza, genius and wildness?

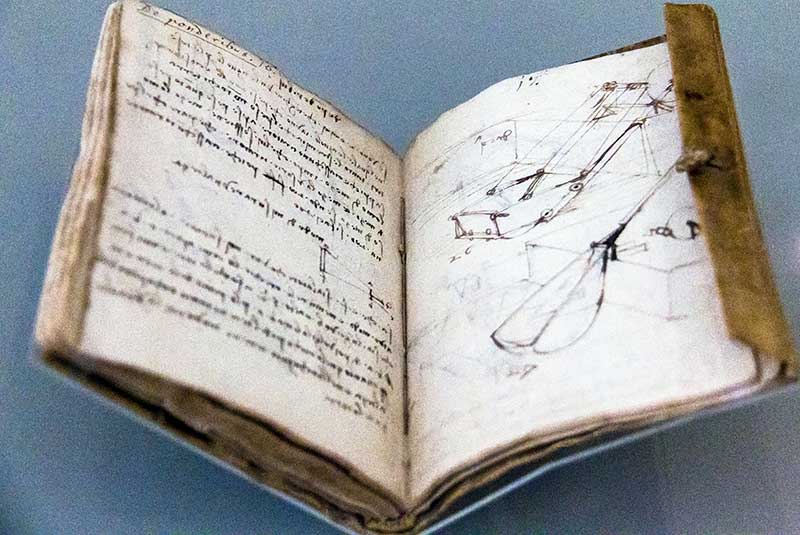

Da Vinci had several notebooks that he used to record his thoughts

The greatness of Leonardo, the reason he still is today, 500 years after his death, the symbol of the immense power and beauty of human genius is because he was the first to demonstrate how utterly complete and beautiful the human mind could be, in spite of its imperfections and its tricky habits; he was the first all round artist, an ultimate learner, the Renaissance embodiment of Dante’s depiction of Ulysses, born to learn because learning is at the heart of human nature. Leonardo opened up the eyes of humanity to what we, as human beings, could really achieve, only with the use of our brain; he created delicate beauty in his painting and sectioned corpses to see how we were made; his hands were no longer able to paint but he still believed there was a way for Man to fly. Leonardo was a genius. And geniuses do not need to have their inventions built or the name of their mothers known.

With all his geniality, Leonardo was also imperfectly, reassuringly human. He never learnt to write from left to right, had some unsavory friendships and a couple of issues with the law. He gloriously failed the choice of his painting technique for the Last Supper and he didn’t finish a series of great works, he was messy and disorganized, as his many notebooks show.

But then, that’s the real essence of Leonardo, the real reason we celebrate his greatness this year and we will always: because his genius was incredible yet human, his hand blessed, but still that of a man. Leonardo was a genius, but he was refreshingly imperfect. That makes him closer to us and very likeable indeed. And of course, there are all the mysteries: who doesn’t like a bit of those?