Reprinted From

Newsletter, Italian American Studies Association

Western Chapter, Winter 2021

Among the features of Prof. Kenneth Scambray’s new book, Italian Immigration in the American West, 1870-1940, that stand out are the episodes he relates coming directly from his Family Papers. These are by no means gratuitous or filio-pietistic boastings about his own immigrant family. Rather, they are integral to his overall thesis, especially regarding two major themes: first, that though early Italian immigrants displayed primary loyalty to their co-villagers rather than to Italians or Italy, they eventually, in America, began to see the virtues and benefits of affiliating with that larger whole. Second—and this was especially true in the West—many immigrants were initially reluctant to adopt American attitudes about racial dividing lines, mainly because they themselves had been the targets of racism, both in an Italy that saw them as tainted by proximity to Africa, and in America. As a result, they were quite willing to fraternize with both African Americans and Native Americans in their new country. The episodes Scambray employs to demonstrate this both concern his grandfather, Vincenzo Schembri (the original family name became ‘Scambray’ in America). In the first, he relates how Vincenzo, having emigrated from his Sicilian village of Bivona to Brazos, Texas to work as a farm hand, married a woman who had settled across the river with her paesani from Poggioreale. Scambray notes that “This ‘bi-cultural’ union would have been next to impossible in Sicily” (42). The point is made: already, in America, the mixing of origins by Italian immigrants, here only from one Sicilian village to the next, has begun. The second episode is even more poignant. Vincenzo Schembri, like many Sicilians in the South, saw no reason to shun the African Americans with whom he worked, and routinely invited them to his home. This soon aroused the wrath of local Ku Klux Klan members in Bryan, TX for whom this was heresy. It prompted a visit from three members of the Bryan community “to inform him that he had to stop allowing African Americans to enter the front door of his house and to stop allowing them to eat at the family dinner table.” Scambray goes on to relate how Sicilians, used to such unfair treatment in Italy, often responded:

Vincenzo relented, but not totally… he ceased allowing his African American friends to enter the front door of the family’s small house. However, he continued to host African Americans out back at the family table next to the barn where the family more often than not took its evening meals (Scambray Family Papers) (48).

The use of his family archives in this way gives added weight to the episode and sears the point into the reader’s mind: that this kind of muted resistance to American racism on the part of Italian immigrants was a common occurrence.

But Scambray doesn’t limit his text to only personal knowledge. He has combed the literature for every bit of scholarly evidence to make his update of the research on Italians in the West and what made their settlement unique likely to become a standard reference text. He references not only the standard works, such as Andrew Rolle’s 1968 classic, The Immigrant Upraised, but a host of other full-length studies and essays and census reports that define his field. This gives the necessary weight to his study that should satisfy even the most meticulous scholars, as well as more general readers.

Scambray departs from Rolle in a number of ways, but perhaps his most significant is in what he covers as “the West.” Rolle considers all states west of the Mississippi River his “West.” This includes states normally considered mid-western states, such as Kansas and Minnesota. Scambray does not. He does include all of Texas, even though much of the state is actually east of the 100th meridian, but he then stays with strictly western states, from Arizona and New Mexico to Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho, then Montana, Alaska and Washington, finally moving on to far-west states like Nevada, Oregon and California. He groups these, in order, into sections titled Southwest, Midsection of the West, North of the West, and Far West. While some of this grouping may seem arbitrary, it provides a convenient organizational framework to what might otherwise be a cumbersome survey.

The book then treats each state individually. For each one, Scambray treats the themes he has pinpointed as having given the western immigrant his particular advantage. The major themes he explores for each are generally the same: how priests, often Jesuits, were the pioneer settlers, establishing missions and schools that typically turned into colleges, and paved the way for immigrants to feel somewhat at home in an otherwise unsettled and unsettling world. He then explores in detail the jobs always crying for laborers—the western mines, forests, farms, and fishing zones that offered the immigrant wages well above what he or she needed for simple survival. This leads to one of Scambray’s major arguments. Where the narrative of eastern immigrants is often one of being trapped in low-wage jobs and harsh conditions, Scambray points out for each state how the daily wage for workers in the labor-starved West was high enough to allow the immigrant to quickly amass enough capital to quit his dangerous entry job and become a “free laborer.” This, in turn, allowed him to pool resources with others, usually family members, and often start enclave businesses, such as a saloon or a grocery. Such independence made him a real part of a community, rather than an outsider.

The advantage of being a free laborer was coupled with one other major boon for immigrants to the West: cheap land. Scambray repeats this theme again and again. The immigrant who was able to save from his wages in a coal mine, for example, was then able to turn the accrued capital into land—land which could be farmed. He was thereupon able to grow much of his own food and eventually become a landowner, something almost impossible in the Italy of his birth. Many farmers in California’s Central Valley, and in other states in the West, thus found that they could begin to amass farmland in productive ways, and to introduce American buyers to fruits and vegetables not initially part of the local cuisine. And most significantly, to focus on the raising of wine grapes to turn much of California and other states into premier wine-producing areas.

This focus on success does not blind Scambray to the darker side of his immigrant narrative. He in fact makes much of the differences in the ways Native Americans and African Americans were treated, compared to newly-arriving immigrants. These two groups, often competing for the same labor-intensive jobs, were denied the advantages given to Italian-Americans, who, for the most part, were considered white or semi-white. This meant they did not endure the same handicaps as Blacks, usually denied the right to own land. Asian-Americans, too, were denied that right by law. So the point, Scambray emphasizes, is that the “struggle” of Italian settlers was made demonstrably easier by their conditional racial acceptance. But this was complicated and sometimes compromised by the above-mentioned tendency of Italian immigrants to fraternize with people of color.

One stirring example cited by Scambray occurred in northern California near the town of Ukiah. There, Italian immigrants worked the same “day labor” jobs, often on farms or in sawmills, as the Pomo Indians. Regarding Indians as co-workers and neighbors, immigrants saw no reason why they should not serve Indians wine at their saloons, or attend dances and celebrations on Indian rancherias. Local authorities looked upon such fraternizing as suspicious at best, and as violations of the law at worst. When some Italian immigrants even intermarried with Indians, the suspicion grew that Italians were foreign anarchists seeking to overturn the social order. It was only when enterprising Italian farmers turned unproductive land into profitable farms and grape-growing areas that local sentiment towards them slowly changed. Nonetheless, Scambray qualifies his account of the Italians’ success with the central acknowledgment that not only were Native Americans and Blacks denied the same success, but that the very lands which were so cheaply available to the immigrants were literally stolen from the Native Americans with whom they were forbidden to associate.

Scambray also makes it a point to treat the crucial role played by women. Each chapter directs the reader to the typical role of Italian women in America in running not just the household, but many of the enclave businesses like saloons, and especially the boarding houses that were so crucial to male immigrants. Without the unpaid labor of women, many of these businesses would have failed. With them, they added to the growing prosperity of Italian immigrants in the West.

Finally, Scambray is careful to bring the story of each settlement up to date by modifying the standard immigrant story of assimilation with what has become a current tendency: that later-generation Italian Americans, contrary to predictions about vanishing ethnicity, have returned, in recent years, to a renewed interest in the “old country.” This has made them, in the current jargon, “transnationals,” with their allegiance split between America and Italy. But since they are much more confident of their full acceptance and status in America, they do not have to worry, as the immigrant generation did, about how this interest in and love for the old country is perceived. They may not know the precise term for their bi-focal identity, but they are quite comfortable with it, nonetheless.

There is much more in this wide-ranging study, particularly its delineating of individual stories of success and/or failure, but that may not be necessary here to conclude that Prof. Scambray’s study, with its breadth of coverage, with its exhaustive reference to the most current literature, is likely to become the standard work on Italian immigration to the West.

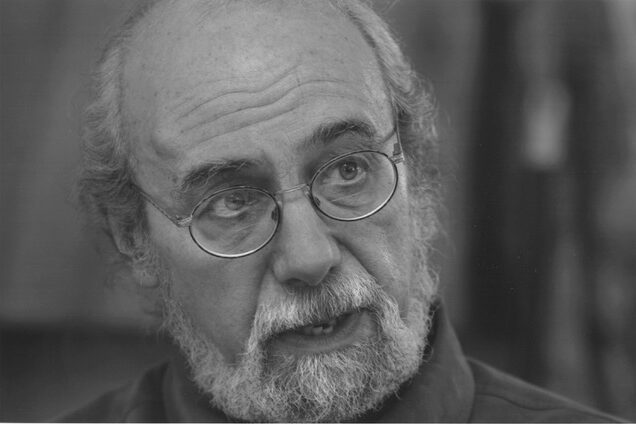

Lawrence DiStasi

Tra le caratteristiche del nuovo libro del prof. Kenneth Scambray, Italian Immigration in the American West, 1870-1940, spiccano gli episodi che egli racconta e che provengono direttamente dalle sue carte di famiglia. Non si tratta affatto di vanterie gratuite o filo-pietistiche sulla sua famiglia di immigrati. Piuttosto, sono parte integrante della tesi generale, specialmente per quanto riguarda due temi principali. Il primo: sebbene i primi immigrati italiani mostravano lealtà primaria verso i compaesani piuttosto che verso gli italiani o l’Italia, alla fine, in America, cominciarono a vedere le virtù e i benefici dell’affiliazione a quell’insieme più grande. Il secondo, e questo era particolarmente vero sulla West Coast: molti immigrati furono inizialmente riluttanti nell’adottare gli atteggiamenti americani sulle linee di demarcazione razziale, soprattutto perché loro stessi erano stati oggetto di razzismo, sia in un’Italia che li vedeva come contaminati dalla vicinanza con l’Africa, sia in America.

Di conseguenza, furono abbastanza disposti a fraternizzare sia con gli afroamericani che con i nativi americani nel loro nuovo Paese.

Gli episodi che Scambray usa per dimostrare questo riguardano entrambi suo nonno, Vincenzo Schembri (il nome originale della famiglia divenne “Scambray” in America). Nel primo, racconta come Vincenzo, emigrato dal suo villaggio siciliano di Bivona a Brazos, Texas, per lavorare come bracciante, sposò una donna che si era stabilita dall’altra parte del fiume con i suoi paesani di Poggioreale. Scambray nota che “Questa unione ‘bi-culturale’ sarebbe stata quasi impossibile in Sicilia”. Il passo era compiuto: in America, la mescolanza delle origini da parte degli immigrati italiani, qui solo da un villaggio siciliano all’altro, era iniziata. Il secondo episodio è ancora più toccante. Vincenzo Schembri, come molti siciliani del Sud, non vedeva alcuna ragione per evitare gli afroamericani con cui lavorava, e li invitava abitualmente a casa sua. Questo suscitò presto l’ira dei membri locali del Ku Klux Klan a Bryan, TX, per i quali questo era un’eresia. Ciò provocò la visita di tre membri della comunità di Bryan “per informarlo che doveva smettere di permettere agli afroamericani di entrare dalla porta d’ingresso di casa sua e doveva smettere di permettere loro di mangiare alla tavola di famiglia”. Scambray continua a raccontare come i siciliani, abituati a un trattamento così ingiusto in Italia, spesso rispondevano di no:

Vincenzo cedette, ma non del tutto… non permise più ai suoi amici afroamericani di entrare dalla porta principale della piccola casa di famiglia. Tuttavia, continuò ad ospitare gli afroamericani sul retro, al tavolo di famiglia vicino al fienile, dove la famiglia spesso consumava i pasti serali (Scambray Family Papers).

L’uso degli archivi di famiglia in questo modo dà maggiore peso all’episodio e fissa il punto nella mente del lettore: che questo tipo di resistenza silenziosa al razzismo americano da parte degli immigrati italiani era un evento comune.

Ma Scambray non limita il suo testo alla sola conoscenza personale. Ha setacciato la letteratura alla ricerca di ogni briciolo di prova accademica per rendere la sua ricerca sugli italiani e su ciò che ha reso unico il loro insediamento, un testo di riferimento standard. Fa riferimento non solo alle opere standard, come il classico di Andrew Rolle del 1968, The Immigrant Upraised, ma a una serie di altri studi completi, saggi e rapporti di censimento che definiscono il campo. Questo dà il peso necessario al suo studio che dovrebbe soddisfare anche gli studiosi più meticolosi, così come i lettori più generici.

Scambray si discosta da Rolle in diversi modi, ma forse il più significativo è in ciò che egli considera come “Ovest”. Rolle considera tutti gli Stati ad ovest del fiume Mississippi il suo “West”. Questo include gli Stati normalmente considerati medio-occidentali, come il Kansas e il Minnesota. Scambray non lo fa. Include tutto il Texas, anche se gran parte dello Stato è in realtà ad est del 100° meridiano, ma poi passa agli Stati strettamente occidentali, dall’Arizona e dal Nuovo Messico al Colorado, a Utah, Wyoming, e Idaho, poi Montana, Alaska e Washington, passando infine agli Stati dell’estremo ovest come Nevada, Oregon e California. Li raggruppa, nell’ordine, in sezioni intitolate Sud-Ovest, Metà del West, Nord del West e Far West. Anche se alcuni di questi raggruppamenti possono sembrare arbitrari, forniscono una comoda struttura organizzativa a ciò che altrimenti potrebbe diventare un’indagine ingombrante.

Il libro tratta poi ogni Stato singolarmente. Per ognuno di essi, Scambray tratta i temi che ha individuato e che hanno dato all’immigrato occidentale il suo particolare vantaggio. I temi principali che esplora per ciascuno sono generalmente gli stessi: come i preti, spesso gesuiti, furono i pionieri colonizzatori, che stabilirono missioni e scuole che tipicamente si trasformarono in college, e aprirono la strada agli immigrati perché si sentissero in qualche modo a casa in un mondo altrimenti instabile e inquietante. Poi esplora in dettaglio i lavori che hanno sempre richiesto manodopera – le miniere occidentali, le foreste, le fattorie e le zone di pesca che offrivano agli immigrati salari ben superiori a quelli necessari per la semplice sopravvivenza. Questo porta a uno dei principali argomenti di Scambray. Se la narrazione degli immigrati orientali è spesso quella di essere intrappolati in lavori a basso salario e in condizioni dure, Scambray sottolinea per ogni Stato come il salario giornaliero per i lavoratori nell’Ovest affamato di lavoro era abbastanza alto da permettere all’immigrato di accumulare rapidamente un capitale sufficiente per lasciare il suo pericoloso lavoro e diventare un “lavoratore libero”. Questo, a sua volta, gli permetteva di mettere in comune le risorse con altri, di solito membri della famiglia, e spesso di avviare attività di gruppo, come un saloon o una drogheria. Tale indipendenza lo rendeva parte vera e propria di una comunità, più che un estraneo.

Il vantaggio di essere un lavoratore libero era accoppiato con un’altra grande manna per gli immigrati nel West: la terra a buon mercato. Scambray ripete questo tema più volte. L’immigrato che era in grado di risparmiare dal suo salario in una miniera di carbone, per esempio, era poi in grado di trasformare il capitale accumulato in terra che poteva essere coltivata. Era quindi in grado di coltivare gran parte del proprio cibo e alla fine di diventare un proprietario terriero, cosa quasi impossibile nell’Italia in cui era nato. Molti agricoltori della Central Valley californiana, e di altri Stati dell’Ovest, scoprirono così di poter iniziare ad accumulare terreni agricoli in modo produttivo, e di offrire ai compratori americani frutta e verdura che inizialmente non facevano parte della cucina locale. E più significativamente, di concentrarsi sulla coltivazione dell’uva da vino per trasformare gran parte della California e di altri Stati in aree di produzione vinicola di rilievo.

Questa attenzione al successo non rende Scambray cieco al lato più oscuro della sua narrazione dell’immigrazione. Egli infatti sottolinea le differenze nei modi in cui venivano trattati i nativi americani e gli afroamericani, rispetto agli immigrati appena arrivati. Questi due gruppi, spesso in competizione per gli stessi lavori ad alta intensità di manodopera, si vedevano negati i vantaggi dati agli italo-americani, che, per la maggior parte, erano considerati bianchi o semi-bianchi. Questo significava che gli italo-americani non sopportavano gli stessi handicap dei neri, a cui di solito veniva negato il diritto di possedere la terra.

Anche agli asiatici-americani era negato questo diritto dalla legge. Quindi il punto, sottolinea Scambray, è che la “lotta” dei coloni italiani fu oggettivamente resa più facile dalla loro pur condizionata accettazione razziale. Ma questo fu complicato e talvolta compromesso dalla già menzionata tendenza degli immigrati italiani a fraternizzare con la gente di colore.

Un esempio eclatante citato da Scambray avvenne nel nord della California vicino alla città di Ukiah. Lì, gli immigrati italiani facevano gli stessi “lavori a giornata”, spesso nelle fattorie o nelle segherie, degli indiani Pomo. Considerando gli indiani come colleghi e vicini di casa, gli immigrati non vedevano alcuna ragione per cui non dovessero servire vino agli indiani nei loro saloon, o partecipare a danze e celebrazioni nelle rancherias indiane. Le autorità locali consideravano tale fraternizzazione come sospetta, nel migliore dei casi, e come violazione della legge, nel peggiore. Quando alcuni immigrati italiani addirittura si sposarono con gli indiani, crebbe il sospetto che gli italiani fossero anarchici stranieri che cercavano di rovesciare l’ordine sociale. Fu solo quando intraprendenti agricoltori italiani trasformarono terre improduttive in fattorie redditizie e in aree di coltivazione dell’uva che il sentimento locale nei loro confronti cambiò lentamente. Tuttavia, Scambray qualifica il suo resoconto sul successo degli italiani con il riconoscimento centrale che non solo ai nativi americani e ai neri venne negato lo stesso successo, ma che le stesse terre che erano così economicamente disponibili per gli immigrati, furono letteralmente rubate ai nativi americani ai quali era proibito associarsi.

Scambray si preoccupa anche di trattare il ruolo cruciale giocato dalle donne. Ogni capitolo indirizza il lettore al ruolo tipico delle donne italiane in America nel gestire non solo la famiglia, ma molte delle attività commerciali di enclave come i saloon, e specialmente le pensioni che erano così cruciali per gli immigrati maschi. Senza il lavoro non pagato delle donne, molte di queste attività sarebbero fallite. Loro hanno contribuito alla crescente prosperità degli immigrati italiani in Occidente.

Infine, Scambray è attento ad aggiornare la storia di ogni insediamento modificando la storia standard dell’assimilazione degli immigrati con quella che è diventata una tendenza attuale: che gli italo-americani di ultima generazione, contrariamente alle previsioni sull’etnia in via di estinzione, sono tornati, negli ultimi anni, ad un rinnovato interesse per il “vecchio paese”. Questo li ha resi, nel gergo corrente, “transnazionali”, con la loro fedeltà divisa tra America e Italia. Ma poiché sono molto più sicuri della loro piena accettazione e del loro status in America, non devono preoccuparsi, come faceva la generazione degli immigrati, di come viene percepito questo interesse e amore per il vecchio paese. Forse non conoscono il termine preciso per la loro identità bi-focale, ma sono comunque abbastanza a loro agio con essa.

C’è molto di più in questo studio ad ampio raggio, in particolare la delineazione delle storie individuali di successo e/o fallimento, ma potrebbe non essere necessario parlarne qui per concludere che lo studio del prof. Scambray, con la sua ampiezza di copertura, con il suo riferimento esaustivo alla letteratura più attuale, probabilmente diventerà il punto di riferimento sull’immigrazione italiana.

Lawrence DiStasi