Dear Readers,

In February we traditionally pause to celebrate lovers (Valentine’s Day) and Presidents. Once Abe Lincoln (February 12) and George Washington (February 22) were honored individually; now they are collectively celebrated on President’s Day (February 20).

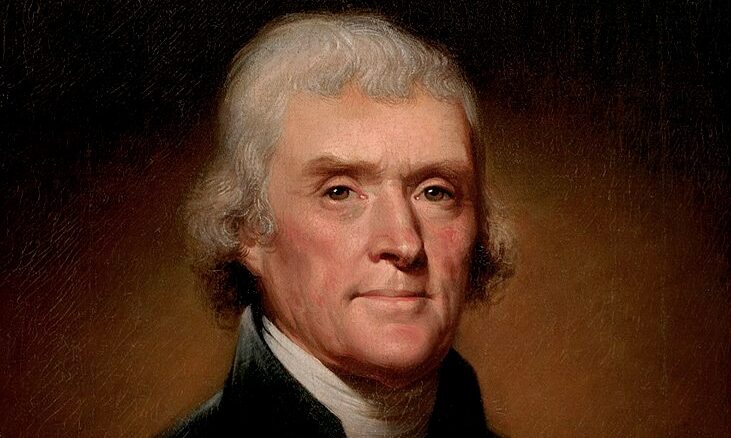

Our third President, Thomas Jefferson, had a lifelong love for Italy and things Italian, as early as 1764, during his college days.

Thomas Jefferson was born in Virginia on April 13, 1743, and died on July 4, 1826. He served as our third president from 1801 to 1809. He was 28 years old when he married a young widow, Martha “Patty” Wayles, on New Year’s Day 1772. He was nearly 40 when his wife died, in 1782.

***

Monticello and Mazzei

The inspiration for the layout and architecture of Thomas Jefferson’s mountain-top home, Monticello, is clearly Italian. There is also ample evidence to suggest that Jefferson’s long conversations with his Florence-born neighbor, a talkative Italian exile-turned-wine-merchant named Philip Mazzei, inspired the language used in the Declaration of Independence. In an article translated by Jefferson, Mazzei wrote, “All men are by nature equally free and independent.”

Philip Mazzei appeared at Monticello in the winter of 1774, accompanied by Jefferson’s London merchant agent, Thomas Adams. He became a houseguest at Monticello, brightening the last two months of the year for Jefferson, who had lost his sister Elizabeth, aged 29, earlier that year. When a series of earthquakes had rocked the buildings at Monticello on February 21, 1774, Elizabeth had run outdoors in the raw winter weather and, confused, wandered away. She was found dead three days later.

Mazzei, then 43, had been trained as a surgeon in Florence, worked as a doctor on a ship, then practiced in the Middle East, before settling in London, where he had been a wine merchant for many years. A well-known horticulturist, he had sailed to Virginia to introduce the culture of grapes, olives, and whatever fruit trees would flourish there, and had brought his own crew of Italian vineyard workers with him. Jefferson indulged in some of his favorite activities: building, gardening, buying and selling land.

He drew up the charter of a joint stock company for his new friend and neighbor, Philip Mazzei, buying a fifty-pound sterling share in a scheme to cultivate silk, grow wine grapes, and raise olive trees on the Mazzei’s slopes near Monticello, all without slave labor, and relying on Italian grapes imported from Tuscany. From April 1774, his notebooks were crammed with plans and expenditures to produce wine in the first large-scale viticulture experiment in North America. According to local legends, Jefferson was able to greet thirty Tuscan winemakers in their own Tuscan accent. The men, who had heard only English for many months, wept.

***

Jefferson on wine

Jefferson, who seldom dined alone, discovered that fine wines and food were a great way to meet informally with political friends and foes, never talking about politics but dropping a hint here and there of how he felt on a subject. He used these nightly dinners as a form of legislative lobbying.

Jefferson’s first exposure to Italian wines had been during his trip to Northern Italy in 1787, and he was particularly impressed with those made from the Nebbiolo grape. He served 250 bottles of Nebbiolo while President but his favorite Italian wine was from Montepulciano, located some 40 miles south of Siena, in Tuscany.

***

Jefferson and women

Meeting the beautiful Italian-born Maria Luisa Conway in 1786 rekindled Jefferson’s love for things Italian. A widower, the celebrated Virginian fell in love with Maria Luisa (Hadfield) Conway the moment they met in early October 1786, while visiting Paris. As soon as Jefferson was introduced to Maria Luisa, he began to devise how he could spend every possible moment with this lively, beautiful lady. Soon, he was thinking to develop projects with an “Italian Connection” to prevent prolonged separations, for instance, a possible visit to view art in Maria Luisa’s birth city of Florence, or brushing up on his Italian conversations, now rusty since the departure of his neighbor Philip Mazzei.

***

Jefferson makes an Italian connection

Jefferson always had a pragmatic side. Especially after a long series of diplomatic checks in London and at Versailles, he had become determined to break the United States’ economic dependence on England and France by forging new trade ties with Italy. Especially interested in diversifying plantation agriculture and improving all laborers’, black and white, conditions in his native country, Jefferson wrote to Governor John Rutledge of South Carolina in 1788, shortly after his tour of the Mediterranean: “Italy is a field where inhabitants of the Southern States may see much to copy in agriculture and a country with which we shall carry on considerable trade.”