Inside the American Tourister suitcase was a historical treasure.

Over two hundred items including photographs, two postcards, two photo albums of pasta factories and five maps were donated to John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, the Queens College first founded in 1979 devoted to documenting and preserving the Italian American experience.

Honoring the wish of his deceased father, attorney Michael Titowksy, Bernard Titowsky brought the extensive collection of rare-book-seller from Queens, to the institute in 1999.

“We have this archive, but we are not an archive,” said Curator Joseph Sciorra.

Sciorra, together with Assistant Director Rosangela Briscese, worked hard on bringing part of this collection to light curating the photography exhibition “Reframing Italian America: Historical Photographs and Immigrant Representations” currently available on the 17th floor of the Calandra Italian American Institute, 25 W 43rd St in New York.

“We didn’t know much about most of the photographs,” said Briscese inside the Manhattan gallery that displays 23 frames.

The two curators had to deal with a massive research.

“What we know about the people and places seen in the photographs comes from the few descriptions written on the front and/or back of the mute images,” as stated on the catalogue written by Sciorra.

“Photographs don’t talk unfortunately,” said Sciorra. “What they capture is for us to infer.”

Briscese said they hope to gather even more information about these photographs that possibly travelled back and forth to Italy and the United States, and it would be wonderful if someone comes in, or contacts us, because know more about them and wants to help us bring the stories of these Italian-American immigrants portrayed to life.

Lavinia Pisani: What do you like the most about the exhibit?

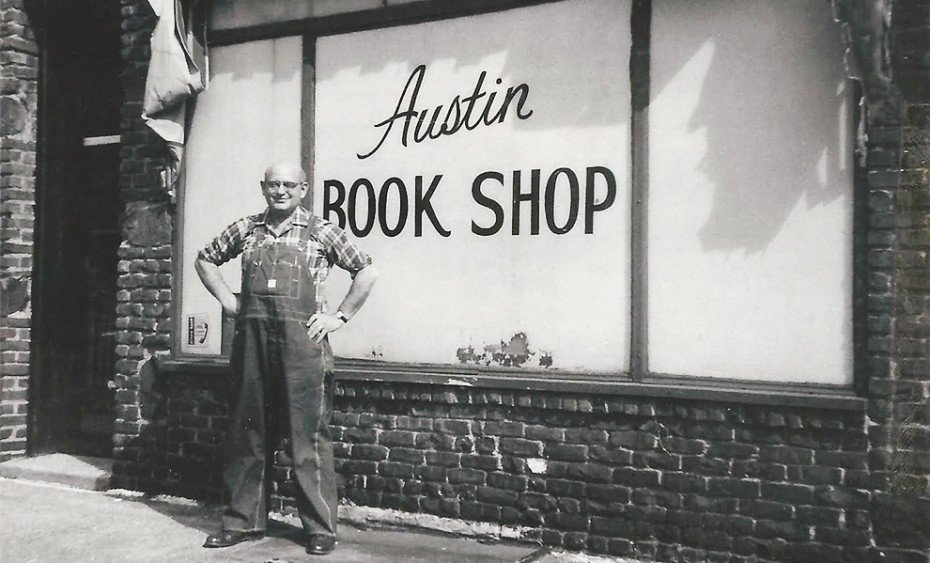

Rosangela Briscese: One of the things is to show how spread out the Italian-American community was throughout the country. Obviously, we are in New York and there are a lot of programming about the New York Italian-American experience, but we love to showcase other parts of the country as well. These photographs provide an example of the diversity of Italian-American immigrants, who experienced both urban and rural areas in the United States. We feel lucky to have these photographs and to showcase Italian-Americans living in Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas, Colorado, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, California, Massachusetts, Missouri and Ohio. Not only is the variety in terms of geographical locations but also in terms of activities they were involved in. Some Italian-Americans is shown were involved with commerce, artistry, religion, and other fields. These are important ranges to show.

LP: Which one is your favorite photograph and why?

RB: A lot of people are immediately drawn to the one of the hat makers in Philadelphia and I like it as well. I hate to make a cliché choice because everyone loves this one, but this is also why we choose it as the cover of our catalogue. It is a beautiful photograph. For one thing, at first you can’t tell they are making hats, it looks like they are making pizza. It is also interesting because most of these photographs of workers are taken in the work setting, like in the fabric, but this one is clear they are posing in a sort of studio, which is interesting to think that this group of hat makers was posing with their materials showing the different phases of production. Also their expressions are beautiful.

Joseph Sciorra: I think my favorite, even if it is very hard to choose, is the one from Bessemer, Alabama. I find the location to be interesting as it is not from a major city, or area. It talks about the relationship of Italian immigrants with African-Americans, which we have come to understand better that has been a historically complicated one. It is particularly exciting to see this relationship portrayed visually. Through Briscesce’s extensive researches, we discovered that in this very small town outside of Birmingham, Alabama, Italian-Americans owned shops that were patronized by African-Americans. The picture was taken in 1911 and as we can all imagine it was problematic to be Italian-American in a bi-racial United States were you were either white, or black, and they weren’t first considered as fully white.

LP: So were Italian-Americans at first discriminated in the United States?

JS: In Italy, Southern Italians were already discriminated by the anthropology that was being perpetuated, especially in the North, that there were two Italian races: a Mediterranean Southern one and an Alpine Nordic. These studies were brought over to the United States at the same time as the Italian immigrants were coming and the ideologies got incorporated into the American culture. When Italians started to come to the United States they were seen as white, meaning they were allowed to own properties, or marry other people. These for example weren’t allowed to African-Americans. Still, Italian immigrants posed a problem to the predominant American racist ideology of that time, as they seemed not to act like white people, and were seen like in between black and white. Eventually, by World War II, Italians were able to create their own sense of whiteness and the larger American society accepted them as overwhelmingly white. So, history changes and that image helps me visualize these dynamics.

LP: Is there a statement about immigration behind this exhibit?

RB: I don’t think we set up these photographs to make a particular statement. One thing that we feel can be viewed is the formality and sense of pride of these Italian-Americans, which is in contrast to the photographs taken, for instance, by Jacob Riis, or Lewis Hine, that show squalid tenements and desperate conditions of immigrants. We believe some of these frames may have been part of a collection exhibited in Italy. So it is notable to think about how Italy may have been viewing its colonies, as they called it, and the connection between the United States and Italy since there is much of back and forth going on. So I think the exhibition was built to show these experiences, and unearthing these evidences, as some of them have been lost. We hope to gather more information about the photographs. Some of them are dated, for example, 1927 and we couldn’t figure out where they were exhibited.

LP: What do you think are the main differences of being an Italian immigrant coming to the United States in the XX century compared to now?

JS: I am co-editing a book with Laura Roberto on Italian immigrations in the United States since the end of World War II (1945-2015.) The differences are many. The First Wave (1880-1924) of immigrants faced no restrictions. People were coming and going. I just learned that my maternal grandfather came something like 27 times back and forth to work and see his family. After the war, during the Second Wave (1945-70’s) there were severe restrictions to come into the country. In between then, and up to now, there is another wave that is smaller and different. Going back to pre and after war, sponsorship also played a big role. At first, people came to the United States with an idea of a chain migration: someone from a small town in Italy would have moved and started to call different people from that town suggesting them to migrate. Afterwards, it was more of a family sponsorship. Clearly, what happened after the 70’s is that people with better education, usually with University degrees, who spoke standard Italian, and were integrated into the national system, were coming to the United States. During the First Great Wave, the idea of Italy didn’t exist for many immigrants as they thought of Italy only as their hometown. Carlo Levi, in his book “Christ Stopped at Eboli”, talks about how some Italians used to associate New York City more than Rome because of their relatives living there.

LP: What’s next?

RB: We are currently planning an event where we are going to showcase the rest of the photographs we have with some extra items so that people can take a special peek, but we haven’t figure out dates yet. It’s going to be late this semester, probably in November.

JS: We would love to see this exhibit travel to California, Alabama, Pennsylvania, and all the other places that are being featured. Also we would like people, scholars in particular, to come and look at the other photographs and use them in their articles, books, so that this material will be even more spread out and available to the public. The exhibit is going to be available until January 8, 2016.