For whoever has chosen to settle in North America, to carry on his/her scientific research, or further his/her field of studies, there is an invaluable resource, ISSNAF (Italian Scientists and Scholars in North America Foundation).

This non-profit organization aims to foster scientific, academic and technological teamwork among Italian researchers and academicians, operating in North America, but also to facilitate an interchange with the world of research in Italy.

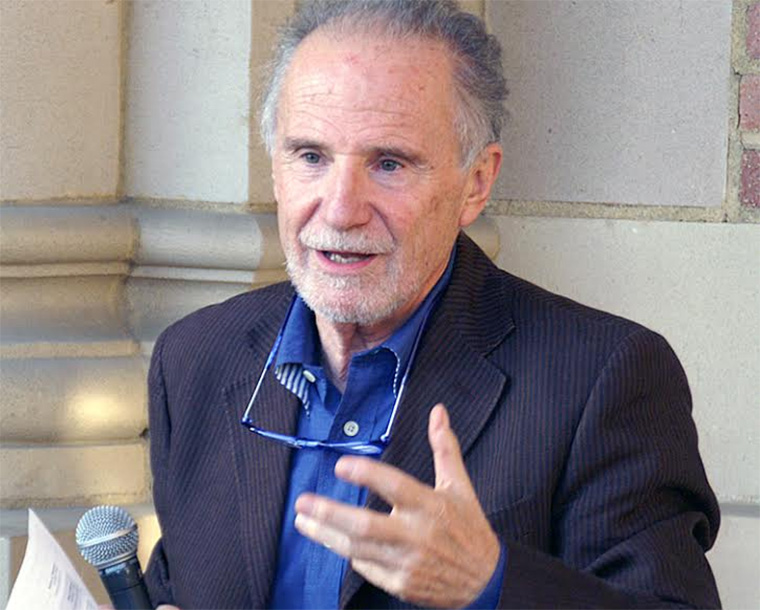

Among its ranks, a special place is occupied by UCLA’s Professor Massimo Ciavolella, whose mastery in Medieval studies, was able to impress late lamented Umberto Eco, who certainly knew a thing or two about the Middle Ages himself.

What is your cultural background?

I was born near Bologna, but I grew up in Rimini, where I attended high school (specializing in classical studies).

Then, I studied at the Universities of Bologna and Rome, before moving to Vancouver (British Columbia, Canada). In the latter, I obtained a PhD in “Classical, Medieval and Renaissance Studies.”

I began my teaching career in Ottawa (Ontario, Canada), at Carleton University, where I remained for fifteen years. After one year in Montreal (Quebec, Canada), as professor at the English-speaking, McGill University, I taught at the University of Toronto (Ontario, Canada), for the following ten years.

Finally, in 1996, I moved to Los Angeles and I’ve been teaching Italian, Medieval Italian and Comparative Literature, at UCLA, since then.

Currently, I’m also the Director of UCLA’s Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies (CMRS).

How was your adjusting process to Los Angeles?

It was not really a difficult one. I’ve moved so often in my life, that, by now, you can regard me as “stateless”.

I already knew people, working at UCLA, before getting here. I really love the campus, with its great library and, above all, the departments where I teach.

I have also the privilege to serve as Director of the above mentioned CMRS, a very active center hosting 75 events, every year.

The best aspect of teaching at UCLA is that you have the freedom to teach whatever you’re passionate about the most. Something that you can rarely see in other academic contexts.

For instance, this year, I taught a course on Medical Humanities, specifically on the relation between mind and body, from Plato all the way to Marsilio Ficino.

Overall, my adjustment process was easy and pleasant.

Share with us your human and professional relationship with late lamented Umberto Eco, one of the greatest Italian scholar and intellectual of all times.

About forty years ago, when I was in Ottawa, I invited Eco to deliver a lecture in our university.

He was affable and easy to get along with. During an informal chat over a glass of Scotch, Bourbon whiskey or, perhaps, white wine, Eco asked me what was my focus of research, at the time.

I had just published a book, “La malattia d’amore dall’antichità al Medioevo” (Love as a disease from antiquity to the Middle Ages, Rome: Bulzoni, 1976).

Eco showed a great interest in it and asked me for a copy, whom I gave him.

In 1980, Eco published his debut novel, “Il Nome della Rosa” (The Name of the Rose). About 30-35 pages of my book were voiced by one of the friars, a character called “Fra’ Massimo of Bologna”.

The latter warns Adso of Melk – narrator and one of the two main characters – about the dangers of falling in love.

Eco told me that the fictional Brother was none other than me. I asked him why he chose Bologna over Rimini, since I grew up in the latter.

Eco replied me that another character, Fra’ Paulus “Agraphicus” (meaning that he doesn’t really write), hailed from Rimini. Inspiration for this other Brother was Eco’s dear friend and fellow semiologist, Paolo Fabbri, a native of Rimini.

The whole matter doesn’t come as a surprise, given that The Name of the Rose, alike the following Eco’s novels, is essentially made of other books.

From that episode on, the bond between Eco and me grew stronger. A few years ago, he invited me to a conference about memory, in Florence.

Recently, Eco received UCLA’s Medal of Honor, which equals to an honorary Degree, since our campus doesn’t confer degrees honoris causa.

Eco owned a vacation house near Rimini, where he spent most of his summers. On those occasions, Umberto, Paolo and I often met for a drink.

I didn’t hear from him, in the last two years, and I intended to invite him to UCLA to take part in a lecture about the History of the Book.

Matter of fact, Eco was a real bibliophile, and had a personal library of 50,000 volumes.

The tragic news of his death struck me off-guard, because I was completely unaware that Eco was struggling against pancreatic cancer.

I cannot say I was one of Eco’s friends, but certainly we had a friendly relationship.

Which, among Eco’s works, was the most influential to you?

According to my formation in Medieval studies, I was chiefly interested in Eco’s works on Medieval philosophy and language. The field of Semiotics, for which Eco was rightly regarded as one of the greatest luminaries, derived from Aristotle and Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Eco considered the Middle Ages as a luminous era. Instead, he was suspicious of the Renaissance, which, to him, was an age of superstitions, rather than articulate thought and philosophy.

Eco’s studies on Aquinas remain largely underrated. In North America, philosophy has taken a different path, a more pragmatic, positivistic one, than the historical perspective, assumed by the Italian “School”.

Just to give an idea, within the distinguished UCLA’s Department of Philosophy, made of over twenty scholars, there is only one Professor of Medieval Philosophy.

These days, in Academic circles, in which Semiotics has lost its status of subject, Eco is losing his past popularity accordingly.

Out of North American Academia, Eco is known for The Name of the Rose and, at a lower extent, for “Il Pendolo di Foucault” (Foucault’s Pendulum, 1988).

Do you think that people outside Europe are familiar enough with Eco’s work?

Certainly, Eco has been always more appreciated in Europe, than in North America.

In a way, the popularity, achieved by The Name of the Rose, worked against Eco, who always regarded his first novel as his worst and only intended it for a limited number of friends.

In the moment in which Eco turned into a “superstar”, the North American Academic world started to look down on him.

In Europe, especially in France, Eco was very well received and appreciated. In Germany and England, he had plenty of followers, as well.

However, since Eco had an “iconoclastic” view of the Academic world and his colleagues, certain serious circles in France disliked Eco’s humor.

Moreover, Eco’s works deal with Saint Thomas Aquinas and Sherlock Holmes, but also comics, and the most intransigent purists didn’t tolerate such a mix of loftier and “lower” topics. They couldn’t label his work and put him in a box, therefore they overlooked him.

Eco was known more as a “cultural agent” and as a novelist, than as a thinker. However, he sought to be recognized as a philosopher of the Middle Ages.

In that direction, our campus, in conjunction with the Italian Cultural Institute of L.A., is going to play its part.

We’re going to honor Eco as a Medievalist, with an exciting lineup of events, to be held at the above mentioned Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies.

On November 3rd, there will be an evening screening of the movie version of The Name of the Rose (by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1986). Special guest is going to be the Academy Award winner, Italian costume designer, Gabriella Pescucci, who worked at the film. We’re trying to secure the attendance of a cast member, as well.

On November 4th, in occasion of a day-long conference, Paolo Fabbri, Eco’s best friend and colleague, will be our guest speaker.

Do you have any contact with the local Italian-American community?

Unfortunately, I have limited ones and I wish I had a lot more.

I’m a board member of Fondazione Azzurra, which promotes a prolific cultural exchange between Italy and Southern California.

My contact with the local Italian-American community occurs mainly through the Italian Cultural Institute of L.A.

In the past, I used to keep more in touch with the Consulate, but the distances make everything complicated.

Lastly, given that the Italian government has conferred on me the title of “Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana”, I take part in several official events.