Dear Readers,

Bits from my bookcase. Here are a few Italian connections I recently found amidst my light-hearted summer reading:

They All Laughed… (Ira Flatow) is a book about inventions that changed our lives and the stories behind them. We Italo-Americans know that it was Antonio Meucci who invented the telephone and not Alexander Graham Bell as we learned in school, however, Meucci was not the only person to run afoul of Bell.

An experienced inventor of Bell’s era charged that he, Elisha Gray, not Bell, was the inventor of the telephone. Elisha Gray took Bell to court in the 1870’s, suing for patent rights to the talking machine. Of course Gray did not win the patent fight; Bell is credited with the invention. But Gray’s claim can hardly be ignored. Sketches of his telephone, produced weeks before Bell’s patent, are remarkably similar. And history might have recorded Gray as the inventor if Bell had not beaten him to the patent office by a few hours.

***

Giovanni Caselli, an Italian priest, invented the telefax machine in 1843, thirty years before Bell’s telephone. The terms fax or telefax, short for facsimile, became accepted technical jargon only in 1980.

The first commercial fax system was invented by an Italian. Giovanni Caselli was considered by his neighbors as “some kind of nut”. With scientific “junk” strewn about the furniture, the Italian priest’s small home looked more like a mad scientist’s workshop than the residence of a man of the cloth.

Born 1815 in Siena, Caselli had simultaneously pursued both theological and scientific studies. Soon Caselli found himself immersed in politics, and before long, his political leadings forced him into exile in Florence in 1849.

The telegraph had opened the world to the convenience of sending messages by code.

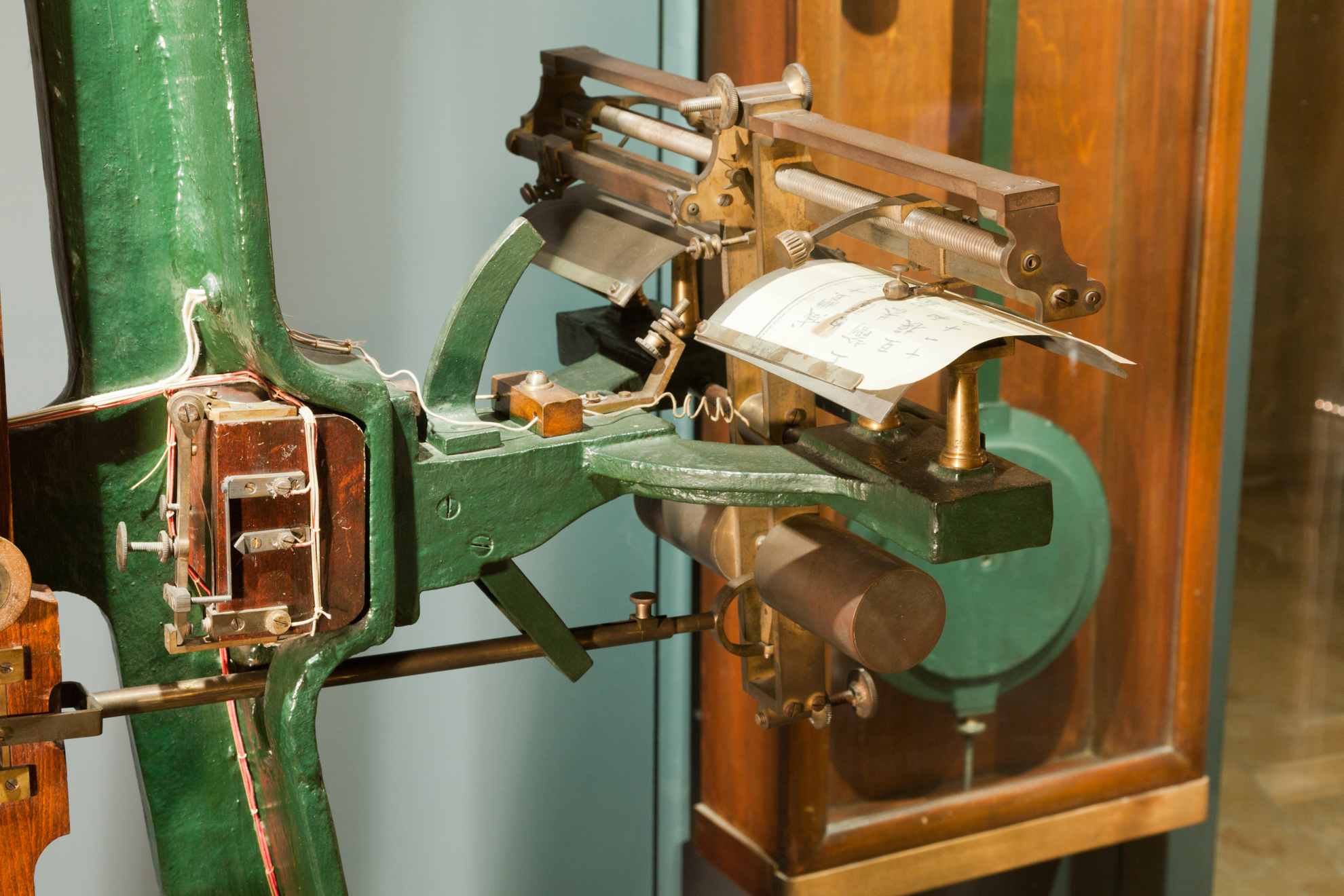

And now inventors turned their attention to a bigger problem: sending pictures by wire was the talk of the electrical community of the day. And Caselli could not resist jumping in with an idea of his own: the “pantelegraph”. Caselli resurrected an idea first thought up by Alexander Bain of Scotland in 1840.

Shortly after the invention of the telegraph, Bain invented a crude method of sending pictures over telegraph wire. Bain was an expert clockmaker, so his fax machine naturally involved swinging pendulums connected at each end of a telegraph line. The machine was never de-veloped (alth-ough patents for the facsimile mach-ine date back to the 1840s), but the kernel of an idea was planted that would later lead to a commercially successful fax machine.

Instead of using a flat plate with an awkward pendulum, English inventor Frederick Bakewell hit upon the idea of a rotating drum. The message was written on the drum with a non-conducting “ink”. The metal sheet was wrapped around a revolving cylinder and a screw mechanism kept the stylus moving along at a uniform rate.

Unfortunately, this design also suffered from a finicky synchronization problem.

Hiding in Florence from his political enemies, Caselli had found a comfortable teaching position at the University. Caselli also tried his hand at publishing. He founded a crude scientific journal called La Ricreazione, which allowed his novel ideas to fall under the gaze of Florence’s elite and educated.

Caselli resurrected Bain’s clock-driven pendulum idea but, lacking the skills to make a working prototype, he set off to Paris to find one of the world’s leading builders of scientific equipment, Gustav Froment. Caselli and Froment labored for seven long years, refining and improving the fax machine. Finally in 1863, Caselli could laugh at the skeptics. He had finally triumphed.

The receiver of a U.S. patent for his “telegraphic apparatus”, Caselli made major improvements to the fax design:

His fax did not require the original to be scratched in metal or written in special ink. Ordinary ink sufficed. Originals could be reproduced in the same size or reduced. Different messages could simultaneously be transmitted through a single wire.

Also among the improvements was Caselli’s very high quality recording paper. It was soaked in potassium cyanide, which changed color each time electricity passed through it. The result was a fax machine standing more than six feet tall, composed of swinging pendulums, batteries, and wires. But this ugly duckling produced faxes of outstanding quality.

The government of Emperor Napoleon III liked what it saw and decided to embrace the pantelegraph as its own. The French legislature passed a law calling for service between Paris and Lyons. In 1861 the government authorized tests of a fax system using telegraph lines between Paris and Lille and Paris and Marseilles. By 1863 a Paris-Lyons line was tested with great success. Transmitting at fifteen words per minute, the fax could send forty telegrams of twenty words each hour. In 1865 the French government decided to take the system public.

Officially inaugurated on May 16, 1865, the pantelegraph was set up on the existing Paris-Lyons telegraph line. The French must have been exhilarated because two years later, the Marseilles leg was added. By 1867 four Caselli machines serviced the Paris-Lyons lines. Service was so improved that by 1868, some 110 telegrams could be sent each hour.

The fax caught the eye of the press (perhaps because they could see its benefits to their industry). Newspapers and magazines praised the new invention for its public service.

The problem with early fax machines was that an owner had to buy the sending and receiving machines from the same maker. Competing brands couldn’t talk to one another. All that changed in 1974, when the first international fax standard was invented by the United Nations.

In 1980, modern office fax machines came into being with the advent of Group 3- a fax standard that allowed digital signals to be sent over regular telephone lines in one minute or less.

***