Even though Dante Alighieri lived more than a century and a half before the Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli, the two of them seem to be linked by some kind of mysterious connection. The famed painter of such masterpieces as The Birth of Venus and the Allegory of Spring, for example, was so fascinated by the figure of Dante that in 1495 he decided to realize a portrait of him which still remains among the most frequent visual representations of the Sommo Poeta. But what is more, Botticelli was always and rightfully captivated, in particular, by the Divine Comedy, to the extent that he even carried out a long series of drawings illustrating the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso as described by Dante. A brand new documentary film by Ralph Loop, titled Botticelli. Inferno, sets out to investigate the missing link between these two geniuses by following the painter’s tracks through Florence, the Vatican, and the rest of Europe. Let’s take a closer look at the story behind it!

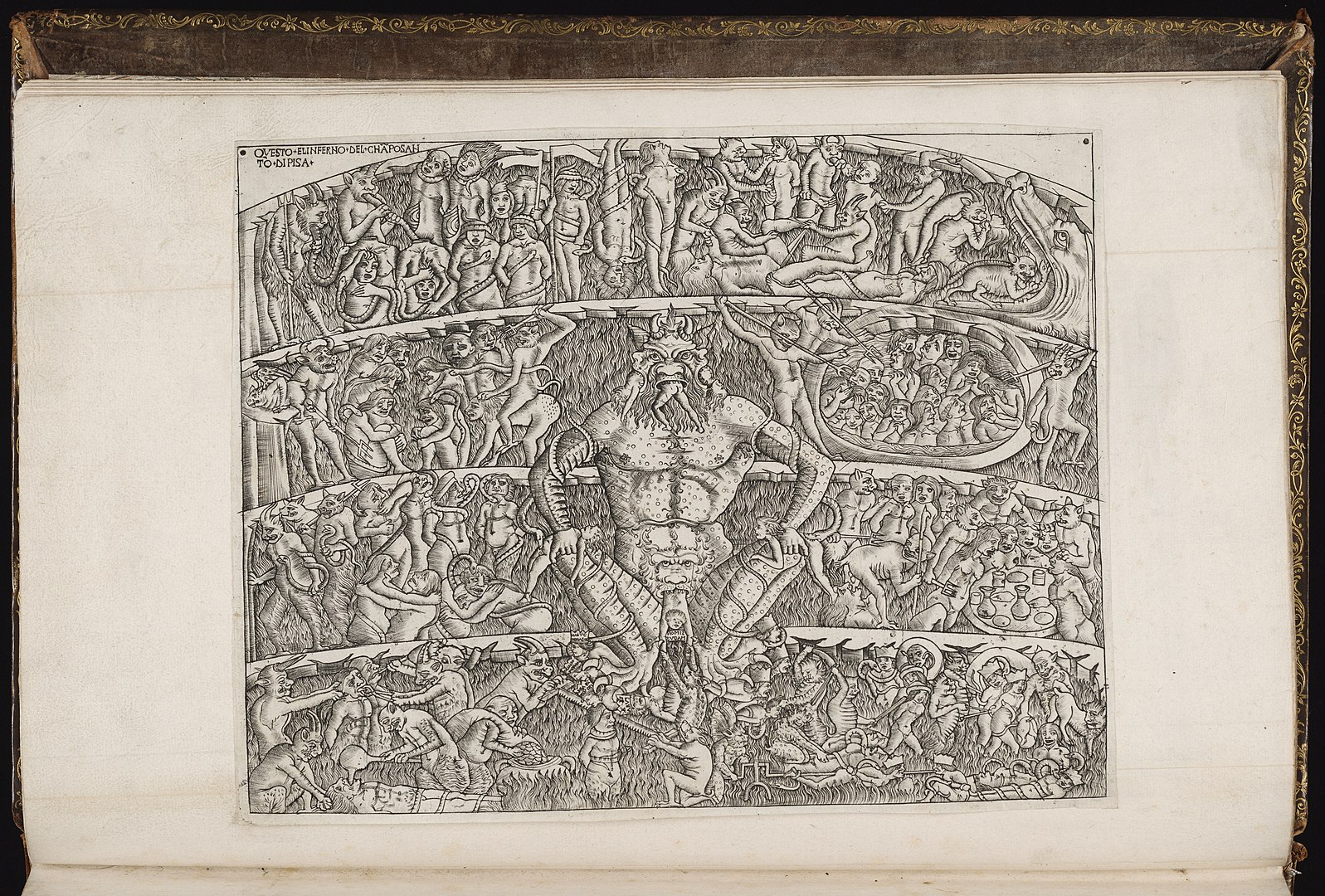

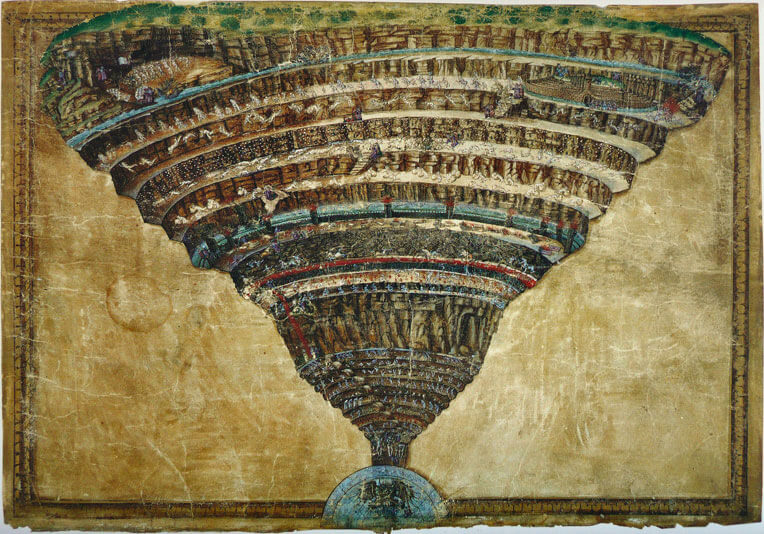

As anyone who has read Dan Brown’s Inferno or watched Ron Howard’s recent movie adaptation would remember, a major role in that story is played by one of Sandro Botticelli’s most meticulous drawings, the so-called “Map of Hell”. This spectacular work of art, which is precisely the main focus of Loop’s investigation, constitutes the real core of Botticelli’s 102 original figures conceived for Dante’s masterpiece (one for each canto, plus two frontispieces). The Florentine artist, who devoted himself fully to such an endeavor for about a decade (roughly between the mid-1480s and the mid-1490s), was commissioned to create these illustrations by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, cousin to the more famous Lorenzo il Magnifico (“the Magnificent”): the result was an unprecedented set of pictured parchments that were intended to enrich a new, refined codex of the Divine Comedy with texts by the scribe Niccolò Mangona.

Eventually, though, something went wrong and this ambitious project was never really completed. Nowadays, the 92 surviving illustrations – most of them unfinished, monochromatic drafts – happen to be split into different collections, as they seem to have been for centuries: 85 of them are to be found – quite peculiarly – in Berlin’s Museum of Prints and Drawings, while the Vatican Apostolic Library contains only seven parchments, including the “Map of Hell”. Unfortunately, there are eight missing pictures for the Inferno that may have been forever lost, while two for the Paradiso were probably not even sketched in the first place.

There surely are several enigmas surrounding these works, at least some of which Botticelli. Inferno tries to explain. First of all, how did it happen that such an important collection by such an eminent painter was scattered all over Europe for all those years and that, at a certain point, it even sank into oblivion? Loop answers these questions by reconstructing not only the illustrations’ actual history, but Botticelli’s life and times as well. Although arguably the most important painter at the court of the Medici during his lifetime, soon after his death the artist’s reputation began to decline and it was not fully restored until the second half of the 19th century: that’s basically the reason why, for about three hundred years, Botticelli’s drawings were forgotten and piled up in who-knows-what European mansion, only to surface again in Lennoxlove House, the Scottish residence of the Dukes of Hamilton, from which they were eventually bought by the Berlin State Museum in the 1880s.

In the end, though, Botticelli’s representation of Dante’s journey to the underworld appears so groundbreaking that its realization becomes in itself a mystery. In fact, the painter did not just provide the Poet’s work with accompanying figures, but he created a whole new form of artistic expression, a visual continuum that was well ahead of its time and which may be considered, in a sense, a distant ancestor of the modern comic strip, if not even of the motion picture. This is clearly the case with Botticelli’s “Map of Hell”: the drawing, which was probably to serve as the magnificent “cover” for the codex, portrays all at once the nine circles of the Inferno as well as Dante and Virgil’s progression through it. In other words, one has to look at the tiny eight-millimeter figures that populate it “one scene at a time”, better still if assisted by a magnifying glass (alternatively, a high-resolution digitalized version has recently revealed many details that were invisible to the naked eye).

With its breath-taking close-ups on some of the most compelling pictures of the Renaissance, but also with its spectacular views on Florence and Rome, Botticelli. Inferno ultimately helps us to understand a darker side of this eclectic master, who managed to paint both the personification of Beauty and the haunting visions of Hell which preoccupied Dante as well as himself.