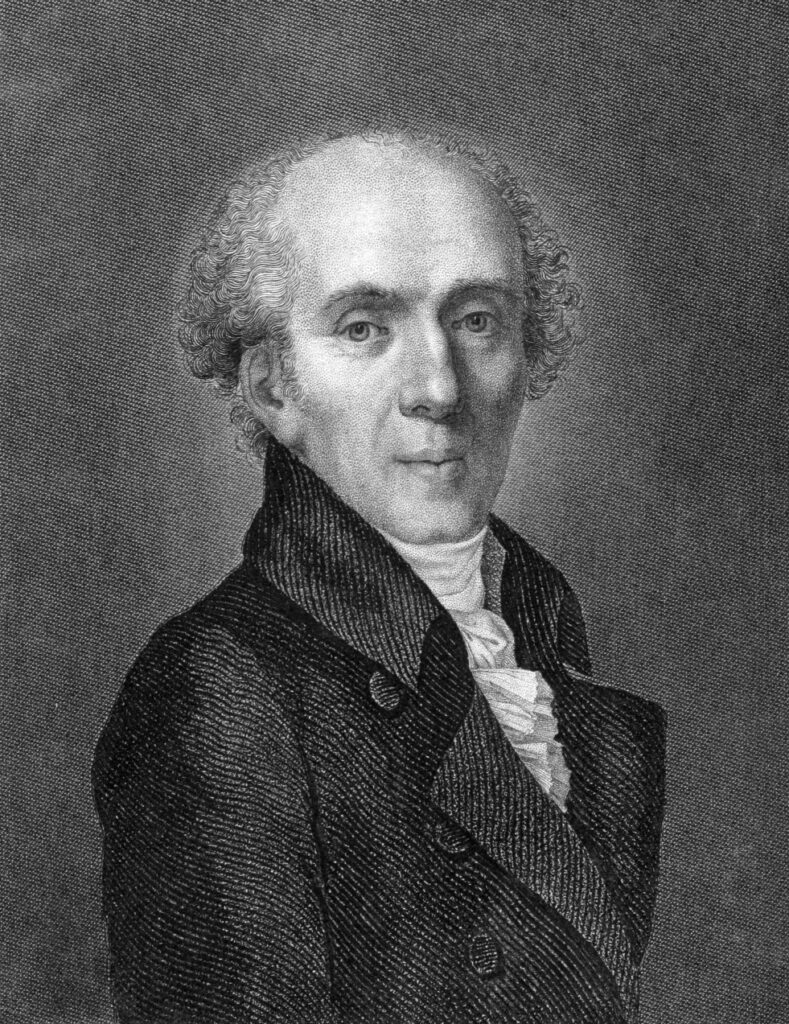

This year we celebrate one of Italy’s most important artistic figures, sculptor Antonio Canova, the main representative of sculptural neoclassicism in our country. Canova, who was born in Possagno, in the Treviso province of Veneto, in 1757, was known to his contemporaries as “the new Fidia” because of how much his work resembled in style and artistry, that of the greatest among all classical sculptors.

As often happens with creative geniuses, Canova didn’t have a simple life, especially during childhood. His father died when he was only four and his mother left him after marrying again. Young Antonio was, then, brought up by his grandparents, a factor that certainly influenced him as a person, but also as an artist: his grandad, Pasino Canova, was a sculptor and a foreman, and introduced him early to the secret of his art.

Legends say that, when he was a child, he participated in a dinner organized by an important Venetian nobleman, Giovanni Falier and that, perhaps bored by the discussions around the table which, we may imagine, must have been utterly heavy for a youngster, he killed some time by carving Venice’s winged lion out of a pat of butter. His host was so impressed by his talent that he decided to become his mentor and patron.

Just a tale, of course, but rooted in truth: Canova’s grandfather had been commissioned a series of works by Falier and, aware of his grandchild’s talent, he made sure Antonio was among the craftsmen at the service of the aristocrat. Falier was so impressed by the youth’s work that he sent him to the atelier of a known sculptor, Giuseppe Bernardi.

In 1768, at only 11 years of age, Antonio moved to Venice, to work and learn under the wing of Torretti: here, he flourished and developed further his talent by attending classes and the Accademia di Nudo and, later, studying the statues at the Ca’ Farsetti gallery, in Rialto. In Venice, Antonio created his first works, commissioned by his patron Falier. In a short time, and at an incredibly young age, Canova became a highly sought-after artist in the Serenissima. At 20, he was famous, and at 22 he became a member of the Accademia Veneziana, the ultimate formal symbol of artistic greatness in the city.

Soon, Venice was no longer enough for Canova and his art: he spent time in Florence and in Rome, where his work became internationally known. He also spent time in Naples. Each step made him better known to a public of sponsors and art lovers who all coveted his works and wanted something for themselves, including the Pope, who commissioned two monuments to the Venetian, including a funerary one. He settled in the Eternal City, even though he spent some time traveling and working around Europe, and also back in Possagno, his birthplace, where he returned for a while trying to recover from a series of physical ailments that had begun affecting him.

Perhaps, the most important work relationship Antonio ever had in his life was that he cultivated with Napoleon Bonaparte. As a Venetian, the artist must have not been too fond of the feisty general from Corsica: it was because of him that the glorious Republic of Venice came to an end after long centuries of glory. But as an artist, the patronage of the emperor was important and could not be refused: for Napoleon, Canova produced a famous sculptural portrait, Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, today at Apsley House, in London, representing the emperor as the Roman god of War and military strategy. The work was completed in Rome in 1806. Two years later, he finished a just as famous piece, Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix, a marble portrait of Pauline Bonaparte – sister of Napoleon and wife to Camillo Borghese, today at Villa Borghese.

Among his most famous – and recognizable – works, we can count also The Three Graces, of which two versions exist, one owned jointly by the Victoria and Albert Museum of London and the Scottish National Gallery, the other at the Hermitage, in Saint Petersburg; and, of course, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, completed in 1793 and today at the Louvre in Paris.

Despite his international fame, Canova never accepted the idea of moving forever out of Italy, which he considered the cradle of art. He died in Venice in 1822 and his beloved country, this year, honors the anniversary of his death with an important initiative that is, at once, a tribute to his greatness, and an important work of artistic conservation: the digitalization of the largest collection of his manuscripts and sketches. The corpus, which is preserved at the Biblioteca Civica di Bassano del Grappa, in the province of Vicenza (Veneto), includes more than 40,000 pages from 6,658 documents such as letters, notes, travel logs and private diaries. The Fondo Canoviano has been digitalized thanks to the interest and support of the Bassano del Grappa library that hosts the documents and has been carried out this year also as a way to commemorate Canova two centuries after his death. The project has been carried out by a group of enterprises leading in the high-definition scansion and digitalization of cultural and artistic patrimony such as Mida Informatica. Hyperborea, a known name in the field of cataloging, is in charge of ordering and cataloging the corpus.