A mile and a half from the Circus Maximus, sheep graze in Caffarella Park. Warming themselves in the April sun, they are indifferent to the ruins of towers and mausoleums and oblivious to an annual rite of spring. Shepherds gather and transport the youngest of the flock for slaughter and sale at Piazza San Cosimato and Piazza Testaccio. As Easter approaches, Rome once again craves abbacchio, suckling lamb.

Abbacchio was a delicacy before the city’s founding. When Italic shepherds roamed free, sheep were Latium’s basic monetary unit, called a pecus. Their skin and wool provided clothing. Their milk, cheese, and meat supplied protein. When Roman law was codified, peculium (the Latin root for “pecuniary”) came to mean transferable property, sometimes in the form of pasturage or livestock. The Divino Amore district, between the Alban Hills and central Rome, was the best range in classical times. The best abbacchio, connoisseurs swear, still comes from here.

According to Juvenal, who satirized Rome’s imperial appetites, true suckling lamb should be “more milk than blood,” killed before it tastes its first grass. The tender-hearted may weep, but the tough-minded shrug. Lambs are not harmless. They nibble everything in sight and compact and erode the soil. Dairy ewes live about a decade, producing up to four lambs a year. When too many threaten to deplete a pasture, ranchers whisk them to the slaughterhouse, the sooner the better.

The term abbacchio reflects this cruel reality. Abbachiare means to beat down or demoralize. The verb derives from bacchiare, to beat fruit from trees with a bacchio, a long stick called a baculum by the ancients. Suckling lambs were carried to the Forum Boarium with their hooves twined over the baculum and were slaughtered with it. Abbachiare also means to sell at bargain-basement prices, to dump on the market, because the overabundance of spring lambs always drives down prices. During the early Christian era, however, butchers jacked prices and gouged customers. Everyone was expected to eat abbacchio at Easter, so demand always exceeded supply.

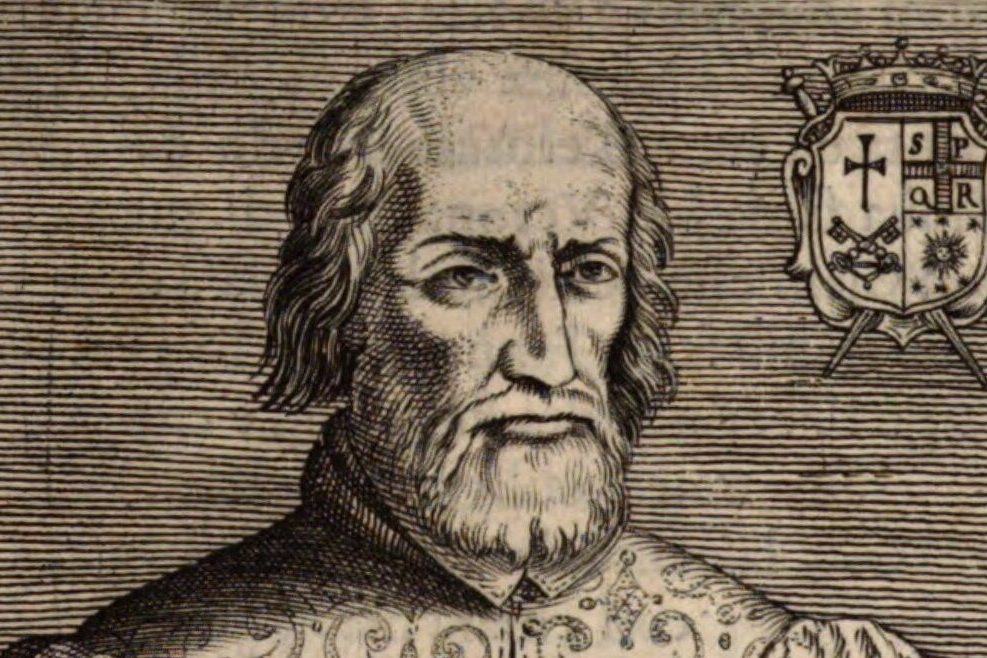

The Lamb of God proved good business. Even the shepherds of the church profited. Medieval popes abandoned to pasture huge tracts of land extending from the gates of Rome to the borders of Tuscany and Umbria. To fund protection against local authorities and to replenish its treasury, the Vatican established a dogana della pastorizia. It taxed all flocks within its purview and collected rent on all pasturage.

Rome also promoted sheep keeping in the Campagna, which belonged to its most powerful families. The Orsini and Colonnas, the Caffarelli and Torlonias converted wheat fields into grazing land. Over time this land became marshy and covered with macchia, maquis brush. Poor drainage bred mosquitoes. Even after quinine became available, most Roman shepherds suffered from malaria. Sallow and shivering, they drove Easter lambs to market, looking like Lazarus.

Tough luck makes tender flesh. Despite its unsavory history, abbacchio is too succulent to resist. Unlike grass-fed lamb, suckling lamb is pale, buttery soft, and sweet. Slaughtered at one or two months old and weighing between 15 to 20 pounds, abbacchio has burned off most of its baby fat but has not developed muscle. Every ounce of the animal is consumed with relish, from legs to ribs, organ meats to intestines. At a trattoria near Campo de’ Fiori, a waiter recites a litany of mouthwatering recipes to Maryknoll nuns on pilgrimage.

Stuff or spice baby lamb with minced rosemary and garlic and roast it with new potatoes. That’s abbacchio al forno con le patate, the centerpiece at Easter dinner. Braise the lamb in broth with white wine and scrambled egg yolks and slurp abbacchio brodettato, an Easter Monday specialty. Cleave it into dainty chops, sprinkle them with rosemary, and grill them for abbacchio scottadito, so named because the chops burn your fingertips. If you sauté the lamb’s internal organs instead, adding slivers of artichoke hearts, you get coratella con carciofi. This hearty dish tastes best on Easter morning around ten, whether or not you’ve fasted on Holy Saturday.

The Mother Superior, raised on a Nebraskan sheep farm, orders pajata d’abbacchio: lamb chitterlings stewed in tomatoes and served with rigatoni. A baby-faced novice wonders whether it is right to eat lamb before Easter but swallows her scruples with the first bite. That’s human nature. We beat our breasts and lick our fingers.

Pasquino’s secretary is Anthony Di Renzo, associate professor of writing at Ithaca College. You may reach him at direnzo@ithaca.edu.