The beautiful walled city of Volterra, an ancient Etruscan town some 45 miles southwest of Florence, is famous for its well-preserved medieval ramparts, museums and archeological sites, and atmospheric cobblestone streets. Fans of American author Stephanie Meyer know it as the setting for the second book in the Twilight series, New Moon.

But Volterra has another claim to fame that is older than vampire tales. Since ancient times, Volterra, a key trading center and one of the most important Etruscan towns, has been known as the city of alabaster.

The Etruscans mined alabaster in the nearby hills and considered it the stone of the dead. The mineral was used for elaborate funerary urns and caskets that housed the ashes of the departed, prized for its durability, beautiful coloration, natural veining and translucence. When the Romans ascended, alabaster fell out of favor and marble became the preferred sculpting material.

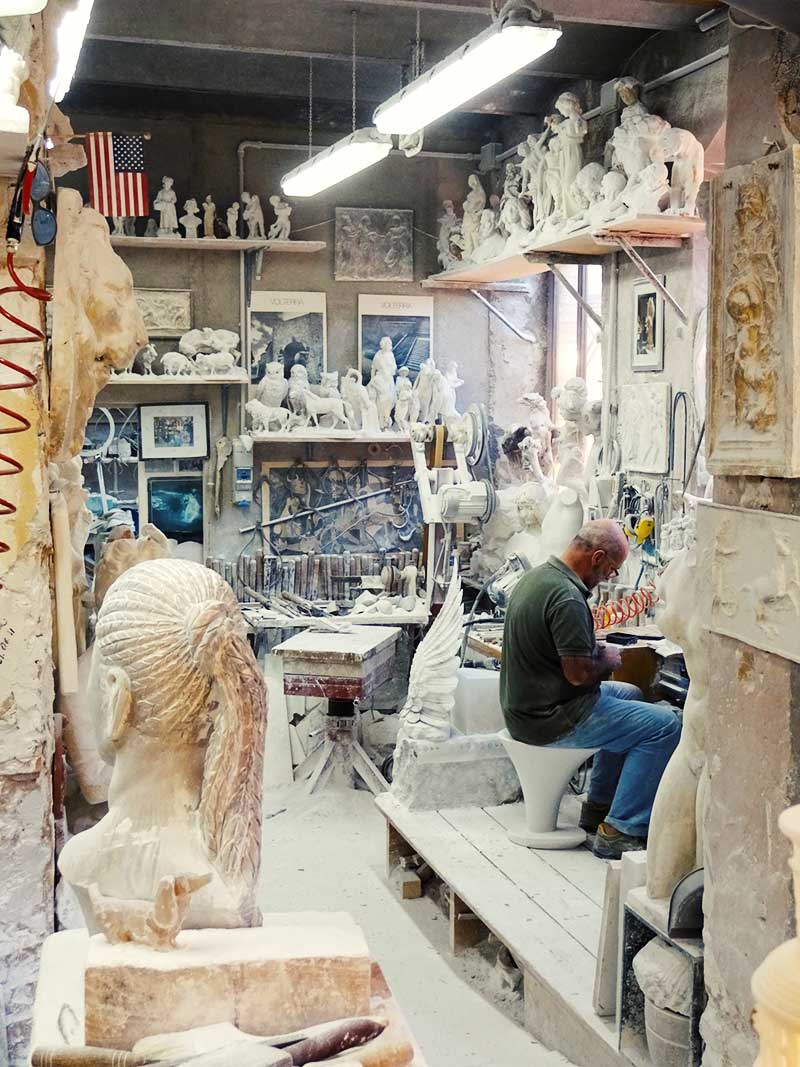

Artist Giorgio Finazzo, co-owner of Alab’Arte, explains some of the techniques used to carve alabaster. (Dale Smith)

Alabaster made a come-back in the mid-1500s when Volterran artists began to slice the translucent stone into thin sheets to make windows for Italy’s medieval churches. At the end of the 18th century, following a period when the stone was again unpopular, alabaster workshops began springing up, and a community of traveling salesmen helped bring alabaster objects to every corner of the globe.

After World War II, there was a push to industrialize the craft, but a handful of Volterran artists insisted on preserving the ancient manual techniques. In fact, the tools and methods used today are almost identical to those used by the ancient Etruscans.

Volterra: a city of Etruscan origins, known for its connection with alabaster © Stevanzz | Dreamstime.com

To work alabaster requires an assortment of hand tools, an artistic eye, and a tolerance for vast clouds of dust. An alabastraio begins with a block or chunk of alabaster. If the final product is to be a vase or bowl, the stone is turned on a lathe similar to what is used to make pottery and then shaped with chiseling tools.

If the alabaster is to be sculpted into heads, busts, animals or other figures, a clay or wax model is often used. Alternately, a pantograph can be employed to accurately transfer the measurements to a larger piece.

Since ancient times, Volterra, a key trading center and one of the most important Etruscan towns, has been known as the city of alabaster

Although alabaster and marble may seem similar in appearance when polished, they are very different materials, particularly when it comes to their hardness and mineral content. Alabaster is a fine-grained form of gypsum, a sedimentary rock made from tiny crystals visible only under magnification. The ancient Egyptians preferred alabaster for making their sphinxes or creating burial objects such as cosmetic jars. The purest alabaster is white and a bit translucent; impurities such as iron oxide cause the spidery veins.

Marble consists mostly of calcite, formed when limestone underground is changed through extreme pressure or heat. It’s not quite as delicate as alabaster and became the preferred material for master sculptors such as Michelangelo who relied on marble from Carrara for his most famous works.

To work alabaster requires an assortment of hand tools, an artistic eye, and a tolerance for vast clouds of dust

To see the stunning artistry of Etruscan-era alabaster, head to Volterra’s Guarnacci Etruscan Museum, one of the oldest public museums in Europe. The collection of archeological objects was started in 1731 by Mario Guarnacci. When he died in 1785, he donated his artifacts to “the populace of the city of Volterra,” transforming a private collection into a public one.

In the museum, visitors can view more than 600 Etruscan urns, arranged according to subject matter. There are rooms full of urns decorated with demons, fierce animals, flowers or masks. Ulysses escaping from the tempting Sirens is a popular subject along with Greek gods and goddesses. Numerous caskets depict images of the people who passed away, lounging on beds or enjoying a meal.

One of the museum’s rooms recreates an alabaster studio from Etruscan times. Although more than 1,000 urns have been unearthed in the surrounding area, archaeologists have yet to discover an ancient workshop, so some of this is guesswork. But because techniques have changed little over the centuries, the tools and furniture on display were simply borrowed from modern-day alabaster artists.

Alab’Arte’s Roberto Chiti works in a studio full of sculptures, hand tools and a fine coating of alabaster dust on every surface. (Dale Smith)

Following a visit to the museum’s Etruscan collection, it’s time to take a look at Volterra’s alabaster industry. In the city center, there are many alabaster shops selling everything from wine stoppers to chandeliers, bowls to jewelry. Several shops have their workshops close by so you can see the craftsmanship, tools and carving process up close.

Walking into the alabaster studio at Alab’Arte is like stepping back into time. Artist-owners Roberto Chiti and Giorgio Finazzo have been partners for 42 years, first meeting as students in art school. “My father owned a bar,” said Finazzo, “so this was not a skill passed down from father to son. But I enjoy the work and am happy to carry on the traditions of this beautiful art.”

The workshop of Gloria Giannelli, located on the ground floor of Palazzo Tortoli, is next door to the Etruscan Museum. Giannelli began working in alabaster in 1980 and was the first woman in Volterra to enter the field. Her particular style of craftsmanship owes much to the traditional arts of embroidery and lace. She even markets her art as “lace-like creations in alabaster.”

She’s won many national and international awards and this past September, her work was featured in Venice in an exhibition of European crafts called Homo Faber.

The Rossi alabaster workshop has been around since 1920. The shop is tucked away on a side street and its entryway is filled with old photographs, chunks of alabaster and dusty vintage equipment. Although the carving methods might be traditional, the products seen in the Rossi showroom are contemporary in both style and design.