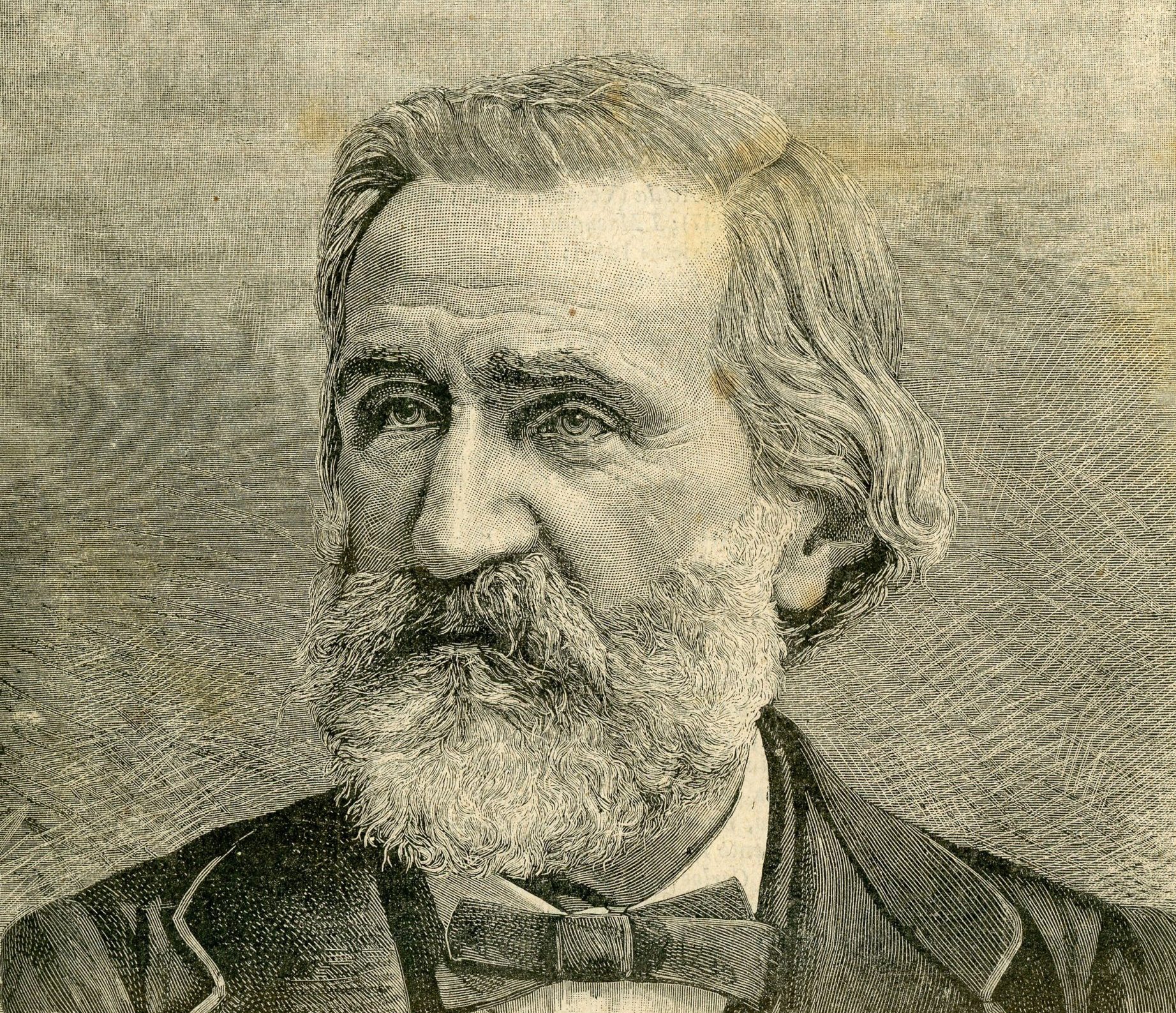

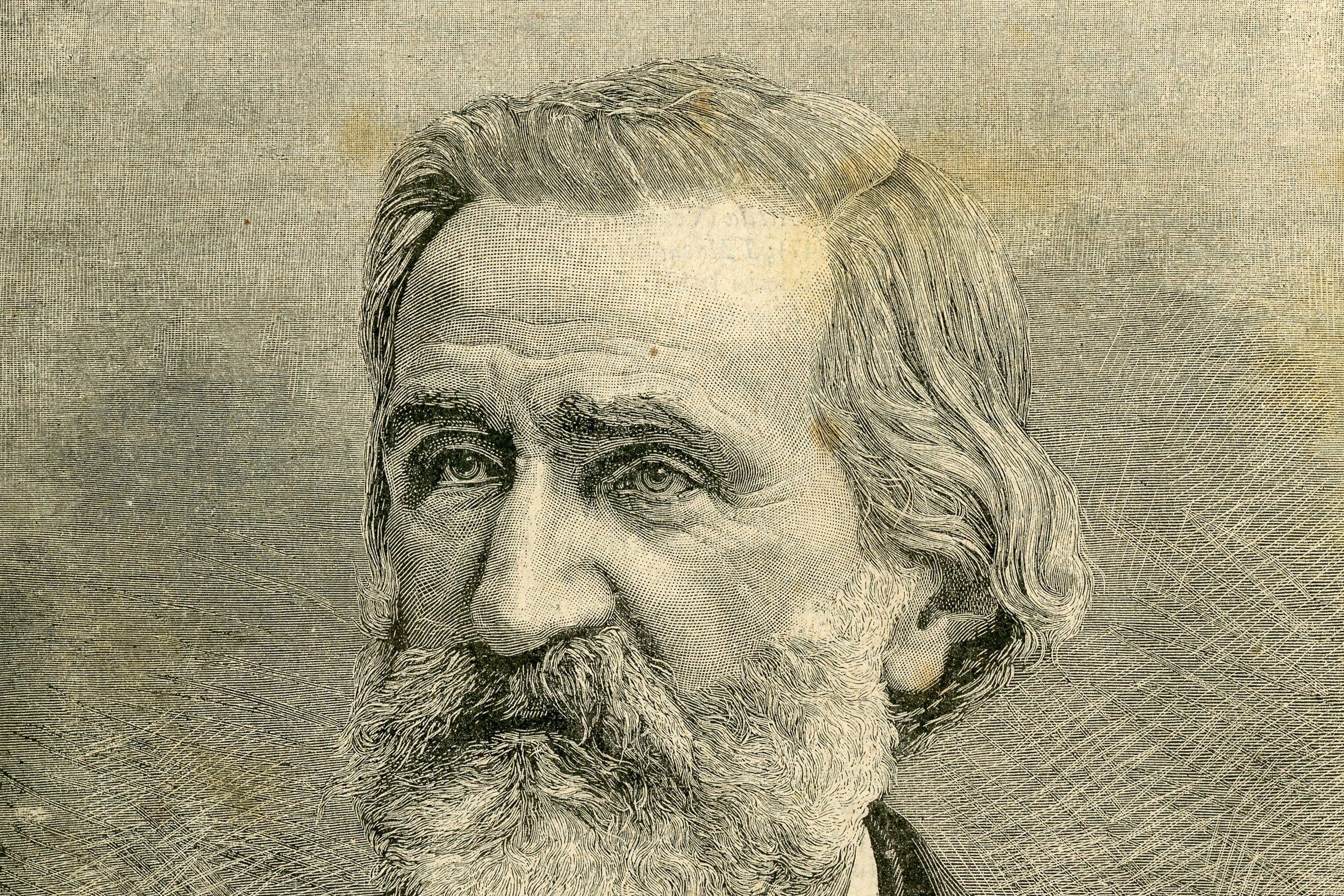

How many times we sing a song without knowing its meaning? It happens that when a song becomes part of the collective heritage of a country, we just take the lyrics for granted. All Italians can intone at least the first verse of Verdi’s Va Pensiero: “Va’, pensiero, sull’ali dorate…”, the words coming automatically to our mind. But who really takes the time to think them over?

The excuse “it is just poetry” seems to be reductive in this particular case, since Va’ pensiero actually represents a hymn against tyranny with a deep historical meaning. Verdi wrote the Va’ Pensiero chorale for his opera Nabucco, named after the Assyrian king Nebuchadnezzar. The story, written by poet Temistocle Solera and inspired by Psalm 137 of the Holy Bible Super flumina Babylonis tells of the conquest of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar (587 b. C.) which marked the Jewish exile to Babylon and the end of the Kingdom of Judah. The choir is made up of Jewish prisoners in chains, who sigh for and dream of returning to their lost homeland.

Verdi uses history as a metaphor to express the Italians’ will to unify a territory divided into small states – many of them dominated by other European countries – into one nation in the 19th century. At the time, Milan was ruled by Austria, and its people’s desire to be free can be clearly read between the lines in the description of the Jewish rebellion against the Assyrian oppressor Nebuchadnezzar. Verdi’s opera succeeded in fueling the revolutionary spirit already rooted in Northern Italy, as all Italian patriotic hearts were reminded of themselves in the sorrowful words of the exiled, enslaved, and oppressed Jewish people. In the same way, the lost homeland Jerusalem actually represented Italy.

Since the very beginning, everybody who listened to it – from cleaning ladies to stagehands and members of the orchestra during rehearsals – couldn’t help singing low those powerful melodies. Nabucco’s strength was irresistible, and it reflected the Italians’ feelings at the time. Its debut at La Scala opera house in Milan in 1842 was an outstanding success, so much that the audience called for encore. Va Pensiero soon became a hymn of the Risorgimento, the Italian nationalist movement. It even made it past the Austrian censors. And at Verdi’s funeral, people spontaneously started to sing it in the streets of Milan.

On the 200th anniversary of Verdi’s birth, the best way to remember this great Italian artist and patriot is to highlight the role that Nabucco played not only in his own life but also in the history of his country.

At the time he wrote it, Verdi was tormented by the loss of his whole family: his beloved wife Margherita and two children had died in 1840. His grief was exacerbated by the Austrian tyranny over the city, and by the fact that his previous work Un giorno di regno had been a fiasco. For all these reasons, he had decided to abandon his career as a composer, and to return to the countryside in the Emilia-Romagna region where he was born. It was only thanks to a chance meeting with the impresario of La Scala Bartolomeo Merelli – who made him read the Nabucco while they were walking through the Galleria De’ Cristoforis in Milan -, that he didn’t give up composing. And Nabucco wasn’t just crucial for his career as an artist: on set he met renowned soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, and their mutual esteem finally turned into a lifelong love story.

Verdi’s opera work Nabucco has a very special meaning for Italy and the Italians. On the one hand, many of them think that the chorale should become the Italian national anthem since – more than any other – it reminds us of our origins, of our history as a country for a long time divided and dominated by foreign oppressors, and of the sacrifice of many fellow countrymen that made Italy’s unification possible. On the other hand, critics affirm that Va’, pensiero actually reflects the tragedy of the Jewish people who suffered defeat and had no hope in a better future. The debate is still open, so much that online petitions can be signed to support the “national anthem” proposal.

In complete opposition with its deepest meaning, the Italian secessionist party Lega Nord based in Northern Italy has chosen Va’ Pensiero as its official hymn, giving as a pretext the author Temistocle Solera’s membership to the political movement known as Neoguelfismo that vaguely shared federalist ideas. This improper use of Verdi’s composition has been harshly criticized by the National Association of Venezia Giulia and Dalmatia area, which underlines instead the historical role played by the chorale in raising Italians’ awareness and promoting national cohesion. Therefore, the community of exiles from Istria, Fiume and Dalmatia has also adopted Va’ Pensiero as a hymn representing the sense of belonging to Italy after the exodus from those territories lost in the Second World War. And, of course, this doesn’t close off space for still other interpretations.

Multiple reinterpretations is testimony to the deep admiration for Verdi’s opera. From the one by anarchist Pietro Gori – who wrote a May Day hymn on the same music of Va’ Pensiero in 1892, in memory of the Fasci Siciliani, a democratic and socialist movement born in Sicily -, up to the recent music chart version half in English and half in Italian by pop singer Zucchero.

In 2011, the last performance conducted by Riccardo Muti in Rome was a huge success. Still today, the slaves’ chorale is able to touch the heart of millions of Italians, it is world-renowned, and makes the audience shudder. According to the conductor, “it embodies the very essence of Italy, and strikes a deep desire for redemption that concerns also contemporary Italy with all its hatreds, scandals, and repressed cultural assets.”

Translation by Silvia Simonetti