Dear readers,

September is the month we celebrate Labor Day and my late father’s Vincenzo’s birthday. It is a good time, I think, to reprint this column from September 2020.

**

I have always felt that, although the accomplishments of our modern-day astronauts and their trip to the Moon are worthy of our admiration, their voyage was undertaken with the backup of thousands, both in personnel and technology. To me, the real pioneers of travel were our fathers and mothers and our grandparents, who left their isolated and obscure villages to begin a journey to what was for them like another planet.

Many immigrant dreams were dashed by the reality that greeted them upon arrival in New York, Massachusetts, and other states of the eastern seaboard. In Lawrence, Massachusetts, some 28 miles from Boston, many different immigrant communities settled because there were plentiful jobs from its burgeoning textile industry. However, in order to keep the wheels moving, the mills depended upon thousands of low-skilled laborers, mostly immigrants arrived during the great wave of European immigration to America that ended in the early 1920s, when the United States imposed a quota on the flow of immigration from Italy. In fact, some Italians traveled to France so they could sail to America from there, as no quota on immigrants to the United States from France had been imposed.

Prior to 1920, thousands of Italian immigrants had been attracted to Lawrence by posters all across the regions of southern Italy, promoting the city as a place where immigrants could find good work and economic prosperity.

Upon their arrival, however, thousands of Italian immigrants realized that they had been seriously deceived by the fake posters. Living conditions were so horrendous that mill workers could expect an average lifespan of only 35 years. The work week consisted of 56 hours for $6.50 a week. Rent for dilapidated housing, which was little more than a cold water flat, was about $3 a week. So, families shared rental space, and they cooked and slept in shifts. In order to survive, everybody in the family who could work, had to work. However, the miserably crowded conditions gave rise to a host of diseases, which accounted for the early death rate. Working conditions in the mills were extremely unsafe, too: hours were long, social security did not exist at the time, and there was no compensation for work-associated accidents.

**

It all came to a head on January 12, 1912, when a new law took effect which reduced the maximum work week hours. However, the textile mill owners were not about to suffer any financial loss and they sped up the wheels of production to make up for the lost hours. That was bad enough, but it got worse when they cut the workers’ pay by two hours. The two-hour difference came to 32 cents a week, the cost of four loaves of bread. So once the deduction appeared in their checks, workers were furious. It began with the Italians and the Polish, who hollered: “Short pay, everybody out!”

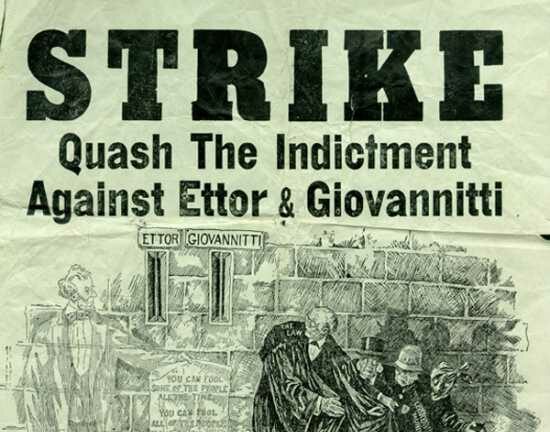

And so, the famous Bread and Roses Strike began. Italians led the two-month strike, affecting 28,000 people who spoke over 45 different languages. Skilled organizers Joseph Ettore and Arturo Giovannitti from the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW, rushed to Lawrence to represent the striking workers. The IWW struck fear into locals and state leaders since it was socialist, some would say communist, in its leanings. At the mayor’s request, the governor sent in uniformed state militia, armed with guns and bayonets, to protect the mills and block the striking workers. The militia also included many students’ volunteers from Harvard University.

There were clashes: the armed militia and the Lawrence police on one side, and the unarmed strikers on the other. Law and order became impossible to maintain. Thousands of angry strikers courted confrontation and defied the militia by daily marches through the streets. Finally, acting to keep their children out of danger, Italian parents sent 240 children by train from Lawrence to New York City, where strangers volunteered to serve as host families. The children were housed, fed, and well cared for until the strike was over.

The sight of the underfed, shabby-looking, pitiful Italian children marching through the streets of New York shocked the nation. Newspapers headlines of innocent children moved Congress to hold hearings. The mill owners capitulated, and the strike ended in March 1912. The workers won a series of pay increases and better working conditions.

Cari lettori,

Settembre è il mese in cui celebriamo il Labor Day e il compleanno del mio defunto padre Vincenzo. Penso che sia un buon momento per ristampare questa rubrica di settembre 2020.

**

Ho sempre pensato che, sebbene i successi dei nostri moderni astronauti e il loro viaggio sulla Luna siano degni della nostra ammirazione, il loro viaggio è stato intrapreso con il supporto di migliaia di persone, sia in termini di personale che di tecnologia. Per me, i veri pionieri del viaggio sono stati i nostri padri, le nostre madri e i nostri nonni, che hanno lasciato i loro villaggi isolati e oscuri per iniziare un viaggio verso quello che per loro era come un altro pianeta.

Molti sogni di immigrati sono stati infranti dalla realtà che li ha accolti all’arrivo a New York, nel Massachusetts e inaltri stati della costa orientale. A Lawrence, Massachusetts, a circa 28 miglia da Boston, si stabilirono diverse comunità di immigrati perché c’erano molti posti di lavoro nella sua fiorente industria tessile. Tuttavia, per far girare le ruote, le fabbriche dipendevano da migliaia di lavoratori poco qualificati, per lo più immigrati arrivati durante la grande ondata di immigrazione europea in America che si concluse nei primi anni ’20, quando gli Stati Uniti imposero una quota sul flusso di immigrazione dall’Italia. Infatti, alcuni italiani si recarono in Francia per poter salpare per l’America da lì, poiché non era stata imposta alcuna quota sugli immigrati negli Stati Uniti provenienti dalla Francia.

Prima del 1920, migliaia di immigrati italiani erano stati attratti a Lawrence da manifesti in tutte le regioni dell’Italia meridionale, che promuovevano la città come un luogo in cui gli immigrati potevano trovare un buon lavoro e prosperità economica.

**

Al loro arrivo, tuttavia, migliaia di immigrati italiani si resero conto di essere stati gravemente ingannati da manifesti falsi. Le condizioni di vita erano così orribili che i lavoratori delle fabbriche potevano aspettarsi una durata media della vita di soli 35 anni. La settimana lavorativa consisteva in 56 ore per $ 6,50 a settimana. L’affitto per un alloggio fatiscente, che era poco più di un appartamento con acqua fredda, era di circa 3 $ a settimana. Quindi, le famiglie condividevano lo spazio in affitto e cucinavano e dormivano a turni. Per sopravvivere, tutti quelli che potevano lavorare, dovevano lavorare. Tuttavia, le misere condizioni di sovraffollamento causavano una serie di malattie, che erano responsabili del tasso di mortalità precoce. Anche le condizioni di lavoro nelle fabbriche erano estremamente pericolose: gli orari erano lunghi, all’epoca non esisteva la previdenza sociale e non c’era alcun risarcimento per gli incidenti sul lavoro.

**

Tutto giunse al culmine il 12 gennaio 1912, quando entrò in vigore una nuova legge che ridusse le ore massime di lavoro settimanale. Tuttavia, i proprietari delle fabbriche tessili che non avevano intenzione di subire perdite finanziarie, accelerarono la produzione per recuperare le ore perse. Ciò era già abbastanza grave, ma peggiorò quando tagliarono lo stipendio dei lavoratori di due ore. La differenza di due ore arrivò a 32 centesimi a settimana, il costo di quattro pagnotte di pane. Così, una volta che la detrazione apparve sui loro assegni, i lavoratori divennero furiosi. Cominciò con gli italiani e i polacchi, che urlarono: “Meno paga, tutti fuori!”

E così iniziò il famoso sciopero del pane e delle rose. Gli italiani guidarono lo sciopero di due mesi, che coinvolse 28.000 persone che parlavano oltre 45 lingue diverse. Gli abili organizzatori Joseph Ettore e Arturo Giovannitti degli Industrial Workers of the World, gli IWW, si precipitarono a Lawrence per rappresentare i lavoratori in sciopero. Gli IWW incutevano timore tra la gente del posto e i leader dello Stato poiché erano di orientamento socialista, alcuni direbbero comunista. Su richiesta del sindaco, il governatore inviò una milizia statale in uniforme, armata di fucili e baionette, per proteggere le fabbriche e bloccare i lavoratori in sciopero. La milizia comprendeva anche molti studenti volontari dell’Università di Harvard.

Ci furono degli scontri: la milizia armata e la polizia di Lawrence da una parte, e gli scioperanti disarmati dall’altra. La legge e l’ordine divennero impossibili da mantenere. Migliaia di scioperanti arrabbiati cercarono lo scontro e sfidarono la milizia con marce quotidiane per le strade. Infine, per tenere i loro figli fuori pericolo, i genitori italiani mandarono 240 bambini in treno da Lawrence a New York City, dove degli estranei si offrirono volontari per fungere da famiglie ospitanti. I bambini furono ospitati, nutriti e ben accuditi fino alla fine dello sciopero.

La vista dei bambini italiani denutriti, dall’aspetto trasandato e pietoso che marciavano per le strade di New York sconvolse la nazione. I titoli dei giornali sui bambini innocenti spinsero il Congresso a tenere delle udienze. I proprietari delle fabbriche capitolarono e lo sciopero terminò nel marzo 1912. I lavoratori ottennero una serie di aumenti salariali e migliori condizioni di lavoro.