Dear Readers, “A man does not have to be an angel to be a saint,” said Albert Schweitzer. The same holds true for Fr. Angelo D’Agostino, founder of Nyubani (Swahili for “home”) and the subject of a new book, DAG Savior of AIDS Orphans, a biography by Joseph Novello (available on Amazon or your local bookstore), whom some people want to see canonized. If you have memories, tales and even material related to Father D’Agostino or you would like to provide testimony to his work and character, you can submit them to www.nyumbani.org/testimonials.

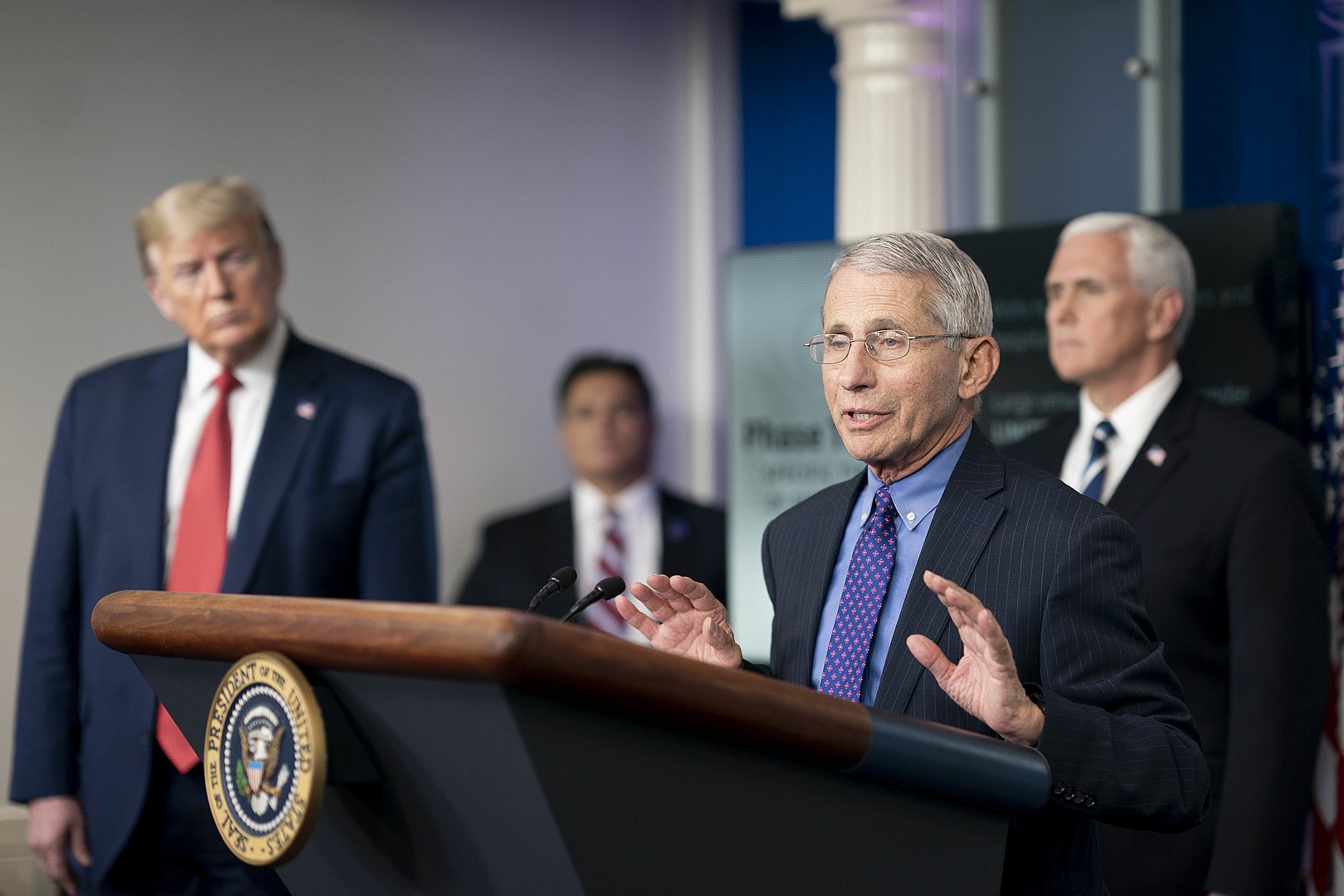

In fact, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the current director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and an authoritative presence during daily press briefings on the COVID-19 pandemic, is one of the people whose wedding was officiated by Nyumbani Founder, Father Angelo D’Agostino. Dr. Fauci was a personal friend of Father D’Agostino as well as a colleague involved early on in the fight against HIV/AIDs.

Let me assure you the book is not boring.

***

I first met Father Angelo D’Agostino (DAG), a Jesuit Priest Doctor, upon completion of surgical training in urology. He was drafted into the US Air Force and spent two years in it as a urologist. Upon discharge in 1955, he decided to change his medical specialty and took psychiatric training at Georgetown University Department of Psychiatry.

In 1971, Dr. D’Agostino was inducted as a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

In 1979, I was in Washington, DC with a group of Italo-Americans from the San Francisco Bay Area, attending the 1st International Conference of the then newly minted 1977 NIAF, when we broke for a late lunch. Father Angelo D’Agostino admired my elegant “America, we discovered it, we named it, we built it” to which I had affixed my “The Nicest People Have a Root In the Boot” button. DAG reached for his wallet and pulled out a list of Italian button titles he had cut out of the Italo-American “Echo,” published in his hometown of Providence, Rhode Island. And that is how our friendship began…

***

DAG and I stayed in touch, and soon I was receiving letters and postcards stamped from places I had never heard of. It seems that Provincial Fr. Arrupe, who was Superior General of the Society of Jesus at the time, was calling for volunteers to work in Thailand with Indochinese refugees. DAG suspended practice and teaching obligations in Washington, DC for one year and set off for Thailand as Director of a medical facility at a refugee camp there. When about to return to the United States, Fr. Arrupe chanced to come through Bangkok.

He mentioned that in Kenya, near Nairobi, a large orphanage was receiving abandoned children who were testing HIV-positive and were not welcome because they were going to “die anyway” and might infect the others.

Returning to Washington DC, Father D’Agostino was able to resume his psychiatric practice, treating mainly family members of Washington’s diplomatic corps. In 1987, he returned to Eastern Africa and was given work as Superior of a retreat house which was in need of expansion. However, as a Doctor, he wanted to help the HIV-positive children.

He rented a house in the Westlands, and by September 1992, he opened a home (“Nyumbani” in Swahili) for three HIV-positive abandoned children. By 1993, he moved to a larger space as HIV-positive abandoned children increased to 24 and by 1995, another move was necessary as the number of children increased to 39. By 1997, 79 children had moved into a newly acquired area and buildings.

By 2002, the ten year anniversary of Nyumbani, established in the slums of Nairobi, there had been expansions to the Nyumbani facilities at Karen. A kitchen house, laboratory, and driveway were completed. Donated solar panel systems and fountains were installed. The local press wrote, “A miracle has happened in Kenya.”

A large part of the “miracle” was Fr. D’Agostino’s battle with drug companies in 2001. In the UK, the Independent Newspaper wrote, “Kenyan AIDS Orphanage Declares War on the Drug Company Giants.” Nyumbani will defy international patent laws and import new AIDS drug from India. The drug is the same, the difference is the price. The western drug costs $3K/year, while the generic from Bombay’s Cipla costs as little as $350.

In 2002 DAG wrote, “At Nyumbani, nobody has died since the drugs got into full swing last August, but if the drug companies succeed in keeping generics out of Africa, the neat little graveyard at Nyumbani will soon be filling up again.”

This was a showdown. The world was watching. The stakes could not be higher, not only for the orphanage of the 94 HIV-positive children, but for all of Kenya, all of Africa, all of the Third World. And, at the center of this life-and-death drama, stood DAG, an overnight hero to the many who could benefit, but a threat to the few who profited.

DAG fans from all over the world flew into Kenya when Fr. Angelo D’Agostino passed away. Born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1926 and died in Kenya in 2006, he is now buried in his adopted country.

Cari lettori,

“Un uomo non deve essere un angelo per essere un santo”, ha detto Albert Schweitzer. Lo stesso vale per p. Angelo D’Agostino, fondatore di Nyubani (“casa” in swahili) e soggetto di un nuovo libro, DAG Savior of AIDS Orphans, una biografia di Joseph Novello (disponibile su Amazon o nella vostra libreria locale), che alcuni sperano di vedere canonizzato. Se avete ricordi, racconti e anche materiale relativo a Padre D’Agostino o volete dare testimonianza del suo lavoro e del suo carattere, potete inviarli a www.nyumbani.org/testimonials.

Il dottor Anthony Fauci, l’attuale direttore del National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease e presenza autorevole durante i briefing quotidiani della stampa sulla pandemia COVID-19, è una delle persone il cui matrimonio è stato officiato dal fondatore di Nyumbani, padre Angelo D’Agostino. Il dottor Fauci era un amico personale di padre D’Agostino e un collega coinvolto fin dall’inizio nella lotta contro l’HIV/AIDS.

Vi assicuro che il libro non è noioso.

***

Ho conosciuto padre Angelo D’Agostino (DAG), medico sacerdote gesuita, al termine della formazione chirurgica in urologia. Fu arruolato nell’aviazione militare statunitense e vi trascorse due anni come urologo. Al congedo nel 1955, decise di cambiare la specializzazione medica e intraprese la formazione psichiatrica presso il Dipartimento di Psichiatria dell’Università di Georgetown.

Nel 1971, il dottor D’Agostino fu assunto come socio dell’American Psychiatric Association.

Nel 1979, ero a Washington, DC, con un gruppo di italo-americani della San Francisco Bay Area, e partecipavo alla prima Conferenza Internazionale della NIAF, allora appena fondata nel 1977, quando ci fermammo per un pranzo tardivo. Padre Angelo D’Agostino ammirava il mio elegante “America, l’abbiamo scoperta, l’abbiamo chiamata, l’abbiamo costruita” su cui avevo apposto il mio “Le persone più gentili hanno una radice nello stivale”. DAG prese il portafoglio e tirò fuori una lista di titoli di citazioni italiane che aveva ritagliato dall'”Eco” italoamericano, pubblicato nella sua città natale di Providence, nel Rhode Island. E così iniziò la nostra amicizia…

***

DAG ed io rimanemmo in contatto, e presto ricevetti lettere e cartoline affrancate da luoghi di cui non avevo mai sentito parlare. Sembra che il Provinciale P. Arrupe, all’epoca Superiore Generale della Compagnia di Gesù, stesse cercando dei volontari per lavorare in Thailandia con i rifugiati indocinesi. DAG sospese l’attività e gli obblighi di insegnamento a Washington DC, per un anno e partì per la Thailandia come direttore di una struttura medica in un campo profughi. Quando stava per tornare negli Stati Uniti, p. Arrupe ebbe l’occasione di passare da Bangkok.

Disse che in Kenya, vicino a Nairobi, un grande orfanotrofio accoglieva bambini abbandonati che erano sieropositivi e non erano i benvenuti perché sarebbero “morti comunque” e avrebbero potuto infettare gli altri.

Tornato a Washington DC, padre D’Agostino potè riprendere la sua pratica psichiatrica, curando soprattutto i familiari del corpo diplomatico di Washington. Nel 1987, tornato in Africa orientale, gli fu affidato il lavoro di Superiore di una casa di ritiro che necessitava di un’espansione. Tuttavia, come medico, voleva aiutare i bambini sieropositivi.

Affittò una casa nel Westland e nel settembre 1992 aprì una casa (“Nyumbani” in swahili) per tre bambini sieropositivi abbandonati. Nel 1993 si trasferì in uno spazio più grande, poiché i bambini sieropositivi abbandonati erano saliti a 24 e nel 1995 fu necessario un altro trasferimento, poiché il numero di bambini era salito a 39. Nel 1997, 79 bambini si trasferironp in un’area e in edifici di nuova acquisizione.

Nel 2002, decennale di Nyumbani, stabilitosi nei bassifondi di Nairobi, ci furono ampliamenti delle strutture di Nyumbani a Karen. Furono completati una cucina, un laboratorio e un viale d’accesso. Vennero installati sistemi di pannelli solari donati e fontane. La stampa locale scrisse: “In Kenya è avvenuto un miracolo”.

Gran parte del “miracolo” era relativo alla battaglia di p. D’Agostino con le case farmaceutiche nel 2001. Nel Regno Unito, il giornale Independent scriveva: “L’orfanotrofio keniota per l’AIDS dichiara guerra ai giganti delle compagnie farmaceutiche”. Nyumbani sfidò le leggi internazionali sui brevetti e importò nuovi farmaci contro l’AIDS dall’India. Il farmaco era lo stesso, la differenza stava nel prezzo. Il farmaco occidentale costava 3K dollari all’anno, mentre il generico del Cipla di Bombay solo 350 dollari.

Nel 2002 DAG scrisse: “A Nyumbani, nessuno è morto da quando i farmaci sono arrivati lo scorso agosto, ma se le compagnie farmaceutiche riusciranno a tenere i generici fuori dall’Africa, il piccolo e ordinato cimitero di Nyumbani presto si riempirà di nuovo”.

Fu una resa dei conti. Il mondo stava guardando. La posta in gioco non poteva essere più alta, non solo per l’orfanotrofio dei 94 bambini sieropositivi, ma per tutto il Kenya, tutta l’Africa, tutto il Terzo Mondo. E, al centro di questo dramma di vita e di morte, c’era DAG, un eroe per i molti che potevano beneficiarne, ma una minaccia per i pochi che ne traevano profitto.

I fan di DAG di tutto il mondo arrivarono in Kenya quando p. Angelo D’Agostino morì. Nato a Providence, Rhode Island nel 1926 e morto in Kenya nel 2006, è ora sepolto nel suo Paese d’adozione.