It seems like fate has bestowed more than just the first name to Donati (13 April 1933) and Leone (3 January 1929 – 30 April 1989), both named Sergio and born in Rome, four years apart from one another.

Together they created a genre, called “Spaghetti Western”, which enchanted and still captivates generations of aficionados, including modern day filmmakers, the likes of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez.

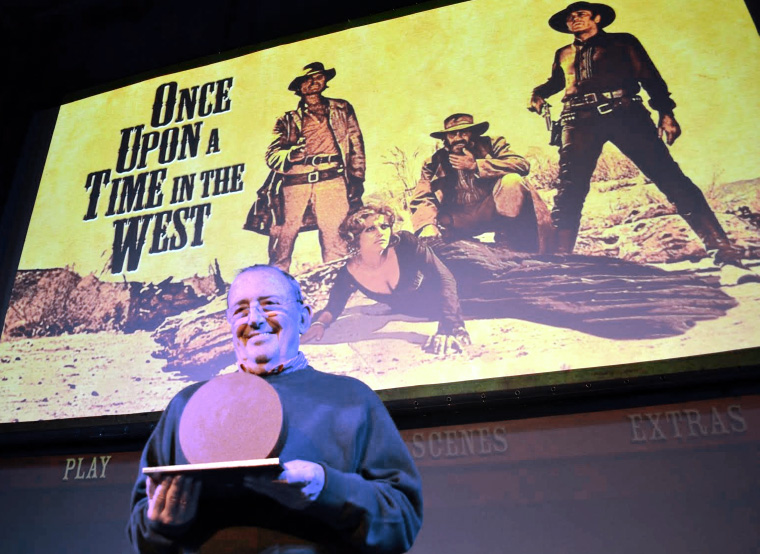

On December 17, Sergio Donati was awarded with the “Tondo”, a prize for Italian excellence granted by the Italian Cultural Institute of L.A.

After the screening of Once Upon A Time in the West, Donati – interviewed on stage by Alessandro Ago Director of Programming and Special Projects, USC School of Cinematic Arts – recalled anecdotes from that golden age in Italian cinema, along with answering some questions from the audience.

I’ve had the privilege of personally interviewing Sergio and have a taste of his straightforward, ironic vision of cinema and life.

In the mid Fifties, you graduated from the Faculty of Law, in Rome, before turning your career’s path into professional writing. Was there any specific episode, which prompted your life’s choice?

I took the degree in Law, without a serious intention to ever become a lawyer or anything alike. While I was still completing my university studies, I submitted my first manuscript to the publisher, Garzanti. However, it turned that down.

In 1955, instead, the Italian publishing series, I gialli Mondadori – directed by the journalist/translator Alberto Tedeschi – accepted my works, releasing my first two crime novels: “L’altra faccia della Luna” and “Il sepolcro di carta.”

In 1956, my third and last thriller, “Mr. Sharkey torna a casa”, got published.

These books drew attention from the movie industry (and later on, two of them would even have been adapted for the screen). Among the filmmakers who reached out to me, there was also Sergio Leone, who back then was still an Assistant Director, eager to direct his first feature.

Writing fiction is highly different from screenwriting. However, this is particularly true in the “American school” and less in the Italian one, in which, particularly in the past, screenplays hold more literary features and qualities. Do you agree?

I don’t totally agree, in the sense that Leone himself asked me to write the screenplay for “C’era una volta il West” (Once Upon A Time in the West), as if it was a novel. The final product was a 420-pages script, filled with extensive scene descriptions, including each character’s feelings.

However, I do share the opinion that the traditional Italian school used to assign an higher literary value to the screenplays, in contrast with the American school.

Leone explicitly asked me to spell out every character’s emotional state, to facilitate the actors’ task of penetrating their minds.

My scene descriptions were so accurate that Ennio Morricone was able to compose the score, just by reading the screenplay. During the actual shooting, his music was played on set, underscoring some of the most moving sequences.

You collaborated on four of Sergio Leone’s major movies. Could you share more with us about your artistic and human relation with this iconic filmmaker?

My whole professional and human experience with Leone is summed up in my book: C’era una volta il West (ma c’ero anch’io) (2007).

Several years ago, a restored version of “Once Upon A Time in the West” was screened at the Rome Film Fest. In that occasion, Dario Argento introduced himself as co-screenwriter for the movie, rather than simply co-author with Bernardo Bertolucci of the initial story, from whom I and Leone developed the film.

My book was intended to make everything clear, once and for all.

My collaboration with Leone started in 1956. He was just four years older than me, despite he looked a lot older. When we came to Hollywood, people even mistook me for his son.

Back then, Leone, who was simply an AD, asked me to write a crime story, set among the mountains. I did as told and wrote a 30-page treatment, featuring a remote mountain lodge. He liked the story, but pointed out: “We need to change the setting with this specific hotel in the Alpine village of Sestriere!” I asked: “Why?”

Leone’s reply was an eye-opener to me: “Because the hotel’s owner is going to finance the film, as well as try to have sex with some of the actresses!”

After this episode, I gave up with the movie industry and moved to Milan. In a few years, I was appointed as creative supervisor, at the second biggest agency, leading advertising campaigns for companies, such as Shell and Barilla.

One day, Leone called me and asked me: “What are you doing over there amidst the fog (RE: Milan’s typical weather condition)?” I replied: “Advertising.” Unimpressed, he told me to go and watch Kurosawa’s film, Yojimbo (released in Italy as “La sfida del samurai”, in 1961), because it might be remade as a western.

I expressed my concerns about Kurosawa’s unawareness and stepped back from the project, but Leone belittled any eventual bad consequence and realized what it would have become: Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964).

The low-budget movie, despite an unsuccessful opening in Rome, captivated movie theater, Supercinema’s owner, in Florence, where it ran for two-three weeks (very unusual occurrence, back then). After the word of mouth spread across the peninsula, the film garnered success and established Leone’s reputation.

Rightfully, Kurosawa and his family sued Leone for copyright’s infringement, since the Italian director didn’t give any credit to the Japanese filmmaker.

Leone and I had a mutual understanding and shared the same creative vision. He urged me to move to Rome and work at the sequel, Per qualche dollaro in più (For a Few Dollars More, 1965).

I rewrote the final scene, in which the bounty hunter, Manco (played by Clint Eastwood), counts the bodies, adding up the bounties, and finds he is short of the $27,000 total. In the previous version, Clint called every corpse by name.

At that time, I was still working in advertisement, but Leone and I made a deal, as he assured me that the producer, Alberto Grimaldi, would put me under contract for a year and remunerate me, at least as much as my previous job.

In the next 8-9 months, I worked in the editing of: Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966). The post-production stage was essential for Leone.

At the same time, I was working at another “spaghetti-western”: La resa dei conti (The Big Gundown, by S. Sollima).

Meanwhile, Leone was starting to conceive the story for C’era una volta il West, with Bernardo Bertolucci – back then, already an accomplished director – and Dario Argento, who was just a film critic at that time.

However, Leone’s collaboration with the two of them was not working out, and, once again, I jumped on board. Upon Leone and I discussing every element of the story, I wrote down the full 420-pages script in twenty days.

In the late seventies and eighties, you worked internationally, collaborating with several directors, and, among them, some British leading figures, the likes of Michael Anderson, John Irvin, and the late Tony Scott and John Guillermin. Let’s go back together over that period.

I recall with pleasure my collaboration with Michael Anderson, for the horror movie, Orca (1977), coproduced by Dino De Laurentiis.

Dino and I were invited to a screening of Jaws, at the screenwriter’s house. De Laurentiis liked a lot the idea of a bad fish, jeopardizing the human community and asked me whether there was another marine animal alike.

Upon some research, I got captivated by the orca whale and its male-female dynamics, which somehow recalled traditional Sicilian relation between genders. In fact, the main plot line deals with a male killer whale, which seeks revenge after its female partner gets killed.

As far as my collaboration with John Irvin, for the action movie, Raw Deal (1986), I co-wrote with my long-time writing partner, Luciano Vincenzoni, a role filled with irony for the protagonist, A. Schwarzenegger, who up until then had exclusively played serious, and unwillingly ridiculous, parts.

From then on, the Austrian-American actor employed the successful formula in the subsequent films, in whom he starred.

And what about your project, never realized, with Billy Wilder?

Billy and I developed a real friendship. He repeatedly invited me over at his house in Malibu. We were planning to do a remake of an Italian movie. However, the project ran aground during the editing stage.

The last movie script you worked to, was the one for The Sicilian Girl (by Marco Amenta, 2008), based on a true story. Are you currently working at something new?

Italian cinema is dead. To me, the worldwide film production is experiencing a downward trend, since the end of the seventies.

The main issue in Italy is that a movie cannot contain any controversial reference to religion or sex, since it always has to be fit for prime time on TV. That is due also to the fact that nowadays RAI Cinema – and not the state – finances films.

For similar reasons, The Sicilian Girl, which had a discreet success in the U.S., has been widely ignored in Italy.

For four years, Amenta and I have been trying in vain to realize Il banchiere dei poveri (Banker to the Poor), about Muhammad Yunus, the Bengali economist and banker, inventor of microcredit and Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 along with his “Grameen Bank.”

Sadly, despite the best Pakistan actor is secured for the cast, along with a renowned American one, neither Italy, nor U.S., nor Pakistan (which literally doesn’t have money), are willing to finance the project.