Young Italian photographer, Giulio Rimondi, is the definition of globetrotter. However, even if you travel low-budget, you still need money, especially if you want to cross the Oceans.

In 2013, affected by the financial crisis, which “brought Italy to its knees”, a flat broke Giulio embarks on a journey across the Italian peninsula.

That’s how the photo reportage, ITALIANA, sprang out. A work, which doesn’t aim to catch the eye with grandiose sceneries, but rather offers an intimate look to a multifaceted Italy.

Giulio and I went back together over the intermediate stages of his professional journey.

Was there a specific episode in your life, which drew you closer to photography?

I approached photography by chance. In spring 2006, in Sicily, I met a maestro, who was running a workshop on the Easter processions in the Italian region, and I attended that hands-on seminar.

Later on, the high-caliber photographer, David Alan Harvey, from the Magnum Photos co-operative, invited me to join him in New York City. There, I met some of the greatest photographers worldwide.

To me, passionate traveler, with a literary background, photography enabled to pursue professionally my globetrotting lifestyle.

What is your cultural background?

I have a traditional classical formation. First, I attended a secondary school focusing on humanities, then I received a Bachelor in Literature and History of Art.

“Humanistic” is also the main attribute of my current photography.

How was your talent spotted? In other words, whom did you first show your work to?

I’ve shown my work to the greatest number possible of people. Nowadays, it’s vital to all the creative artists to hone their social skills and to engage in networking.

The first person, who showed genuine appreciation for my work, was the late lamented French gallery manager, Charles Zalbert, who was the last one to set up an exhibition on Picasso, while the legendary artist was still alive.

While I was in Paris, I had a chance encounter with Charles. I was impressed by an exhibition, held at the Galerie Lucie Weill Seligmann Zalbert, and asked to talk to the gallerist. His assistant rejected my request, but Charles came out of his office and greeted me.

Over the years, we kept in touch and, a short time before passing away, he hosted my first solo exhibition.

I feel gratitude towards Charles, who believed in me and nurtured my talent.

Tell us how the 2008 financial crisis inspired your current project, Italiana.

The 2008 financial crisis coincided with my professional ground floor, which happened to be harder than anticipated.

Between 2008 and 2013, most of the art galleries, with which I collaborated, shut down. Concurrently, newspapers were drastically reducing their number of issues, and gaining photos from agencies, or simply publishing copyright-free pictures.

In 2013, I run out of the necessary budget to travel abroad. I told to myself: “Expand your knowledge, before complaining.” Thus, by living on makeshift means, I embarked on a journey across the Italian peninsula, in the aftermath of the economic crisis.

The adventurous aspect of my travel enabled me to break barriers and to keep always an empathetic look at people.

Was there an encounter, particularly intense and memorable to you, during your photo reportage across Italy?

I had a memorable encounter while I was traveling in Calabria, specifically in the Aspromonte, the mountain massif in the province of Reggio Calabria.

As I spent some days photographing shepherds, they told me there was an old lady still leaving alone in the surroundings of an abandoned village, in the heart of the rough mountain mass. That place is a ghost town, which was abandoned in the 50s, consequently to a major natural event.

It took me time and effort to reach the ghost village. From there, it followed a long quest to find her place, which was hidden nearby.

As I entered the house, a sort of cavity, the old lady was shivering in the semidarkness, in front of a poor fire. I sat next to her and asked a few questions. She didn’t reply, nor uttered a single word. Her mind was completely absent, while she kept staring at the ceiling. In all probability, she was mentally disturbed.

I was perhaps the first human being, she met in decades. As I was leaving, I said goodbye to her, in Italian, as I don’t speak the local dialect, nor I understand a word of it.

She looked at me and replied, in perfect Italian: “Goodbye to you.” Then, as if nothing had happened, she resumed staring at the ceiling.

Was there a place in Italy, which was different from what you expected, or which impacted you more than others?

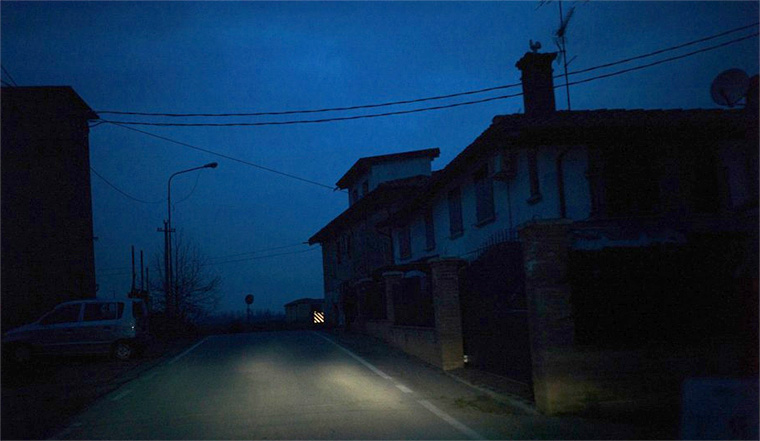

The Padan Plain and the valley through which the Po river flows, had a great impact on me and on ITALIANA. These lands are flat and foggy. They are very cold in the winter and extremely hot in the summer.

They are untouched lands, as tourists don’t have many incentives to go there. Yet they hold great human interest, since villages, in that timeless region, are autonomous micro-communities, like an archipelago of islands.

As I was traveling there, I felt like I was somehow touching one of the many cores of Italy. A less evident, yet greatly representative one.

As far as photographic books, Beirut Nocturne, is your first project . What makes it unique?

From my point of view, there are two aspects, which make it unique. First of all, the young age, in which I realized it, given that I was just twenty-six years old. Back then, I had a fresh perspective on Beirut. Now, after having spent a lot of time in the Lebanese capital city, I feel I could not do the same work again.

The second aspect is the disillusion, which followed the publication of the photographic book. I was convinced that, by signing with CHARTA – one of the leading publishing houses specializing in art books – I would have had a certain professional stability guaranteed.

The 2008 crisis, which led the publisher to go bankrupt, had its share in crushing my early dreams.

Your second book project, Feel Good Lost, seems built more around universal themes, rather than a specific geographical place. Do you agree?

Feel Good Lost, is named after the debut album by the Canadian indie rock band, “Broken Social Scene”. It is an unofficial project, in-between my first and second book, Italiana, scheduled to be published, on November 2016.

Feel Good Lost is a collection of the “scrap” material, originated in ten years of photographic activity. Its quality was not intended to necessarily stand the comparison with my official work. Nevertheless, its fascination derives from painting the full picture of me and my travelling across, more or less, thirty-five countries.

I gathered together moments, which didn’t find room in my photo essays, and structured them around three significant themes: Errance<span>; <=”” span=””>Restlessness and Solitude, which give title to the corresponding three passport-sized booklets.</span>;>

The snapshots are in black and white, with the exception of a colored one, which represents the surprise element.

What is your passion project?

I conceived my life’s project, while I was in Sicily, at the inception of my photographic career.

My ambitious goal was and still is to define culturally the Mediterranean Basin. At 22, I embarked on a two-year journey across the Mediterranean region.

From that experience, I set my mind on a large-scale project, called Mediterraneum, on the cultural identity of that geographical area.