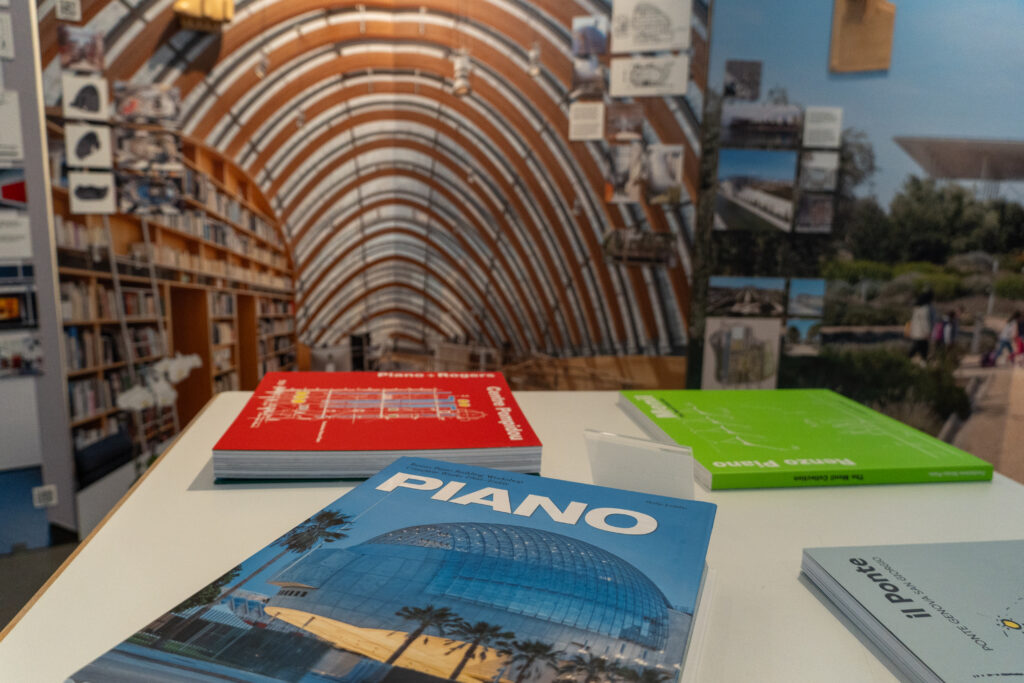

The Italian Cultural Institute in Westwood has inaugurated the exhibition Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Le fil rouge, dedicated to the most significant projects of the Renzo Piano Building Workshop, an international architecture firm made up of twelve partners and led by the Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano. With offices in Genoa and Paris, the Renzo Piano Building Workshop has followed and completed over 140 projects around the world, including the Tokyo Marine headquarters in Tokyo, the Paris Nord Hospital, the new campus of the Politecnico di Milano in Milan, the Pathé Palace cinema complex in Paris, the Center for Arts & Innovation in Boca Raton, and the new Sarasota Performing Arts Center.

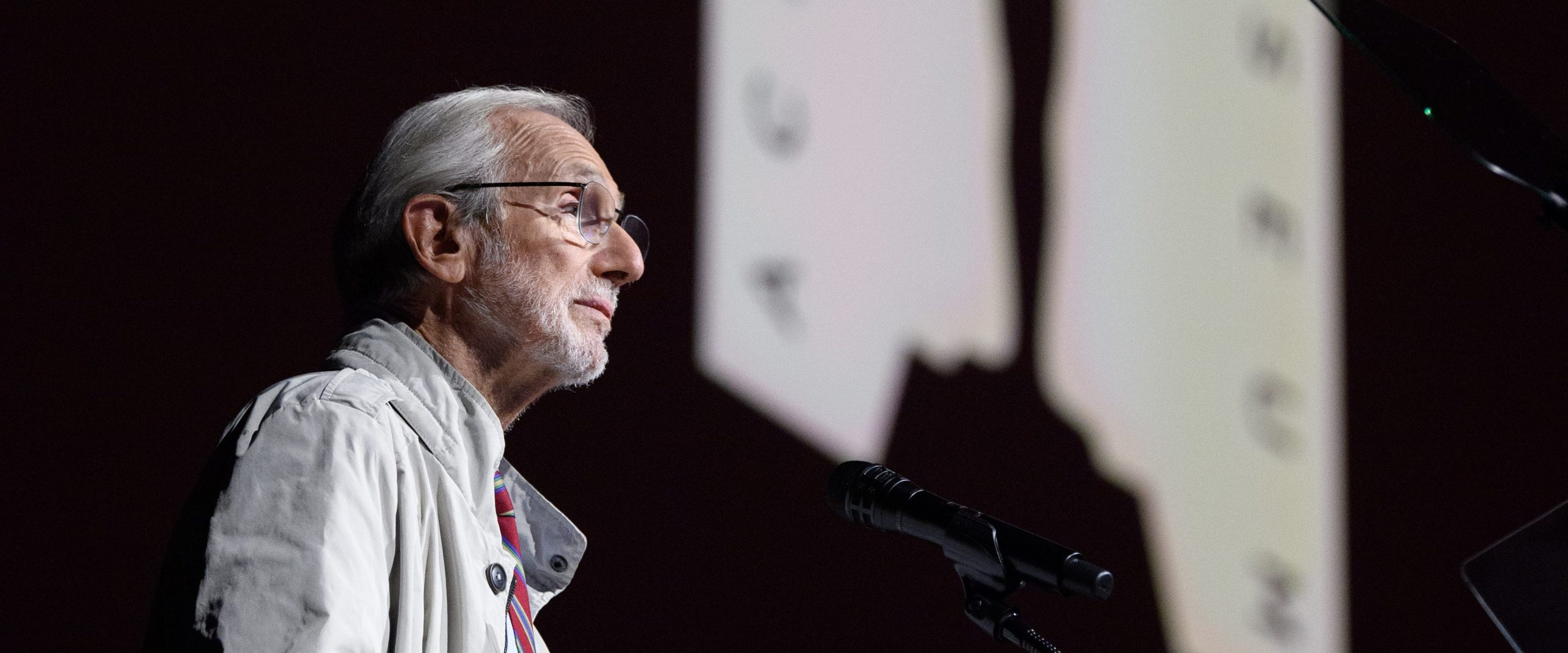

For the opening, the Institute organized a roundtable discussion featuring Luigi Priano, partner at the Renzo Piano Building Workshop; Shradda Aryal, Executive Vice President of Exhibitions at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles; and David Pakshong, senior associate at Adamson Associates Architects, formerly project director at Gensler during the construction of the Academy Museum. The conversation, moderated by architect Elena Manferdini, Chair of the Graduate Program at SCI-Arc, focused on the relationship between architecture, art, and science, sustainability, and innovation.

“We chose to showcase the design and construction process of some projects completed over the last fifty years, from the Centre Pompidou in Paris and The Shard in London to the Auditorium Parco della Musica in Rome and the Pediatric Surgical Hospital in Uganda, providing a snapshot of the studio’s work in the United States,” said Luigi Priano, who joined the Renzo Piano Building Workshop in 2011 and became a partner in 2021. His first project was the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, completed in 2015. Along with Mark Carroll, he also led the teams working on the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, completed in 2021, and the Whittle Schools & Studios campus in Washington D.C., completed in 2020.

Dr. Priano, the Academy Museum is one of your standout projects, which you followed for all nine years of development. What was the initial idea?

First, we asked ourselves how to renovate the Saban Building, a symbol of Los Angeles, and how to add something that would better represent the contemporary nature of cinema, which is continually evolving. It was quite an interesting challenge because filmmakers and those involved in cinema are very creative, so many immediately provided us with inspiration. The bar was set very high quickly; the client always supported us and often set even more ambitious goals than we had imagined from a design perspective.

How did these requests translate into practical terms?

By creating a project with flexible materials and a flexible layout. Ultimately, the solution was found by collaborating with the Academy team and placing the more traditional museum part inside the existing building, which had a very regular structural grid and lent itself well to a flexible exhibition space that they update almost annually. On the exterior, we restored and reconfigured the existing building and created this new wing, the sphere, within which we collaborated with Dolby on sound. The projectors inside the two rooms, including an underground room beneath the museum, can display any film, from nitrate films to 3D movies, bringing to light our initial idea that the cinema museum would have two spaces where you could view the history of cinema from its beginnings to the present day.

One thing that struck me about the exhibition is the attention to waste reduction. Is architecture now focusing on sustainability?

It is fundamental to consider it, not as a slogan but as a modus operandi. To return to the Los Angeles project, renovating the former May Company department store from 1939 rather than demolishing and rebuilding it is a clear example of this. Consider that in 2005, we inaugurated the California Academy of Sciences, the San Francisco science museum, which was one of the first major buildings in the U.S. to receive Elite Platinum certification. We have a holistic approach to architecture because we consider not only the use of materials but also the building’s entire lifecycle: the energy it will consume when completed, the energy used to build it, and how much energy was used to produce the materials it is made of.

Is there another project you’ve worked on in the U.S. that represents this philosophy?

The project for Columbia University, where we built a small campus with a focus on minimal consumption and recovery.

You are also responsible for the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and the Levante Waterfront in Genoa. Can you tell us about the Baltimore project?

It is a very interesting building, relatively small at 6,000 square meters. It was created in collaboration with the Stavros Niarchos Foundation from Athens and the Agora Institute, which aims to study the evolution of democracy, from variations and weakening of democracy to how it evolves in our societies and the factors leading to changes. It will be inaugurated in the spring, between April and June 2025. It’s a small building with a grand mission.

Renzo Piano has won numerous architecture awards throughout his career, including the Pritzker Prize, the AIA Gold Medal, and the Sonning Prize. What is his current approach to work?

He is very present, dynamic, and attentive. I am the youngest partner, at 41 years old, so I joined last, but the office has a quite interesting history because, at Renzo’s insistence, we are 120 people between Paris and Genoa with a zero-growth policy. This means we do not grow in numbers; we only take on projects that we can handle, making a rigorous selection of the proposals we receive. Thanks to this choice, Renzo has the energy, time, and strength to be involved in all aspects, dealing daily with every project.

What have you learned working with an architectural genius like Renzo Piano?

I have always been struck by his humanistic and humble approach. Renzo doesn’t approach problems as an expert or technician, but always maintains a very open vision and a keen curiosity. He has taught me not to find answers on my own, but to try to understand the reasons behind things. This helps us work collaboratively, as if we were a large orchestra. Renzo never presents himself as an architect who has built 300 or 400 buildings around the world; I’ve never heard him say, “We’ve already done this.” He always has this desire to seek different solutions and continually challenge himself, an approach that I think is excellent for life in general, not just architecture.