Being a chef in the Renaissance wasn’t as you would imagine: restaurants as we know them today didn’t exist and the only people who could afford to pay someone to cook for them were kings, lords and Popes. And while Renaissance cuisine has a bit of a niche following, with cookbooks and websites dedicated to it, there’s an uncharacteristic paucity of words about the men who made all that culinary grandeur possible.

That’s strange, if you think that thanks to their geniality — and possibly a good dose of luck — delicacies such as egg and cream based gelato, biancomangiare and even panettone were invented.

Renaissance nobility had a penchant for flamboyancy on the table: think of full roasted wild boars sitting on enormous silver platters, or peacocks decorated with their own feathers, just to give you an idea. Add pots of rose water to delicately cleanse your fingers between one dish and the other and, voilà! A perfect dinner party Renaissance style is served.

Then as today, we learn through the words of Platina in the De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine, there were superstar chefs. Or better, there was one superstar chef, Maestro Martino da Como. He was the perfect cook and, Platina assured us all, the one who brought together Medieval tradition and an elegant research for balance that certainly attracted the Humanists of the time.

Renaissance lords were generous also with their helpers, our modern day kitchen staff, and to private bakers

Elegance and balance? What about the wild boars and peacocks? Well, Platina wrote in the 15th century and in the 16th things were to change a little. In the 1500s, chefs become more independent and creative, they tend to follow less pre-existing models and more their own creative inspiration: they didn’t change much since then, if you think about it. What has changed, however, is the way the worked and where. While today’s most popular chefs are professionals in charge of their own businesses, the Gordon Ramsays and Massimo Botturas of the Renaissance were kings and Popes’ employees: they ran their kitchens, prepared their banquets and, we can bet, they probably also got reprimanded every now and then, if their creations were considered subpar.

The interesting thing, however, is that in the Renaissance Gordon and Massimo could have worked together in the same kitchen, something unlikely to happen nowadays: indeed, a king or a Pope’s kitchen would have more than one head chef, responsible of managing work and organizing dishes on different weeks. All had the same authority and could receive help from one another during the weeks they were in charge.

Coming to the knitty-gritty of their lifestyle, it appears they actually were treated quite well; their lord had the duty to provide new clothes to them at least once a year, they had the right to a private bedroom with a bed (not necessarily a given for other workers of the palace, who may sleep on hay stashes), candles and wood for the fire during the cold season, in the same quantity gentiluomini (gentlemen, or members of the bourgeoisie) were entitled to.

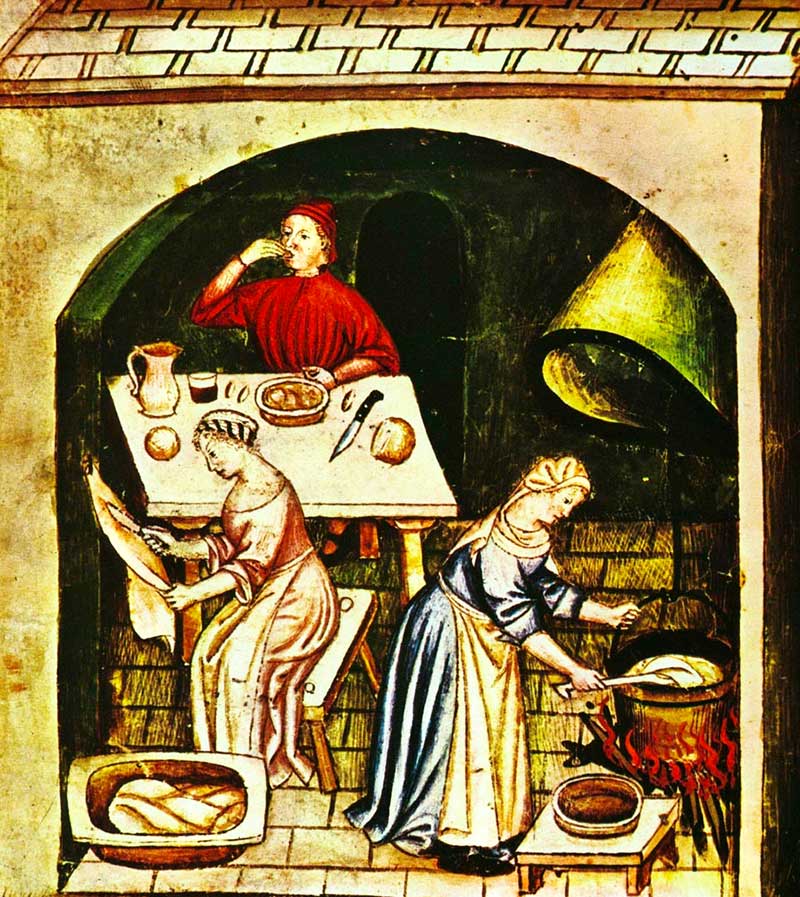

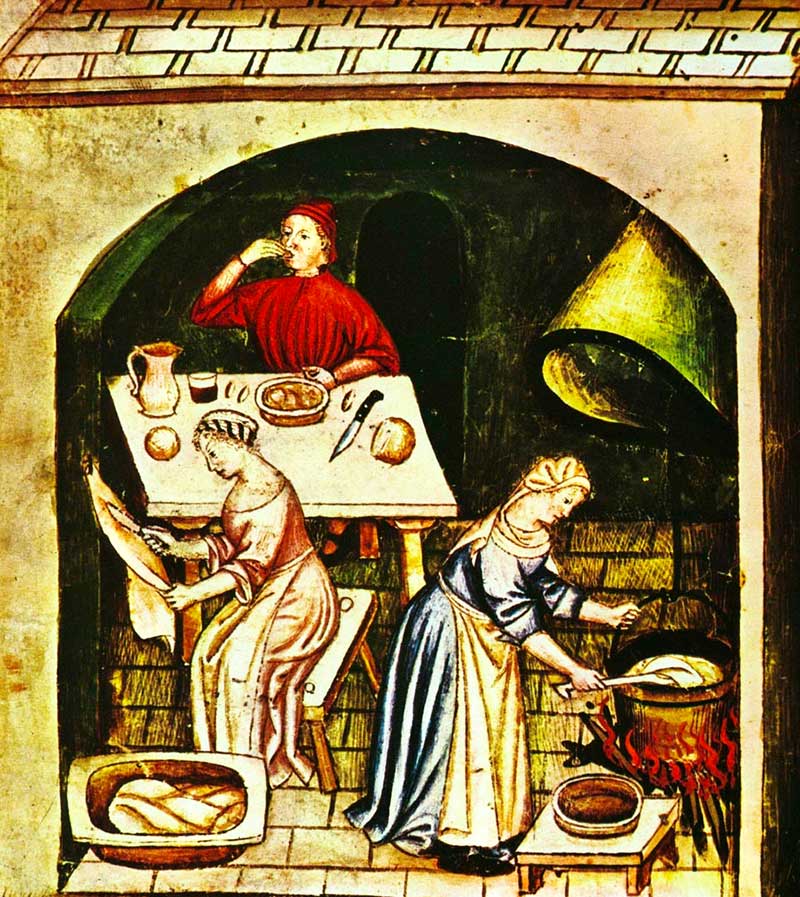

A colorful Renaissance banquet. In those times, chefs at court were well respected

When they were hungry, they could certainly eat a lot: they had right to 1 kg (a bit more than 2 pounds) of bread and almost three liters of wine per day, of the same quality used for gentiluomini again. And what about meat, cheese and other foodstuff? Unfortunately, sources are not as clear about that, however, we know that in the most important courts of Europe head chefs were allowed about 2 pounds of meat (veal or hen, depending on what was on the menu for their lord on that day). This was, of course, for regular days: in what we call in Italian giorni di magro, that is, those days when meat cannot be eaten in respect to religious precepts, chefs would receive 8 eggs per day, in substitution of meat. During Lent, they were given 2 and half pounds of fish instead.

Great chefs, working in important courts, then, had a pretty nice life, at least when it comes to food and accommodation: of course, their job must have been as exhausting as it is today, so let’s say they quite deserved it. But Renaissance lords were generous also with their helpers, our modern day kitchen staff, and to private bakers. They also had the right to their own room and beds and received the same amount of bread and wine of their boss, even if the quality of the wine wasn’t the same. 1 pound and a half of meat, fish — or 6 eggs — a day were also guaranteed. Apparently, lords were quite eager to treat chefs, cooks and the rest of their kitchen team well, so that they would be faithful and, most importantly, they could endure the hard work in the kitchen.

Even if an employee, a lord’s head chef had complete freedom when it came to hiring — and firing — staff for his kitchen, and no interference from other staff members of similar importance was accepted.

Last, but not least, a head chef had to be free and able to travel, and his lord had the duty to make sure he could do so. Why? Quite simply, because at the time nobility moved often from a palace to another, a bit like Elizabeth II does today when she moves from Buckingham Palace to Scotland for the Summer. Of course, it was expected that the head chef and his staff would follow, and they had to do so in comfort and with ease, so they were all entitled to their own horse, walking shoes and everything one may have needed to cook on the go.

And so, they were quite important, our chefs of the Renaissance: they were well paid, they were well fed and very much respected. I wonder if some of them, beside the mentioned Martino da Como, ever reached superstar status: likely yes, but their names may have got lost in the spires of time.

Fare lo chef nel Rinascimento non era come si potrebbe immaginare: i ristoranti come li conosciamo oggi non esistevano e le uniche persone che potevano permettersi di pagare qualcuno per cucinare per loro erano re, signori e papi. E se la cucina rinascimentale ha un seguito di nicchia, con libri di cucina e siti web ad essa dedicati, c’è un’inconsueta scarsità di parole sugli uomini che hanno reso possibile tutta quella grandezza culinaria.

Strano, se si pensa che grazie alla loro genialità – e forse a una buona dose di fortuna – sono state inventate prelibatezze come il gelato a base di uova e crema, il biancomangiare e persino il panettone.

La nobiltà rinascimentale aveva un debole per la stravaganza a tavola: pensate ai cinghiali arrostiti seduti su enormi piatti d’argento, o ai pavoni decorati con le loro piume, solo per darvi un’idea. Aggiungete vasche di acqua di rose per pulire delicatamente le dita tra un piatto e l’altro e, voilà! E’ servita una perfetta cena in stile rinascimentale.

Poi, come oggi, c’erano gli chef superstar e lo scopriamo dalle parole di Platina nel De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine. O meglio, c’era uno chef superstar: il maestro Martino da Como. Era il cuoco perfetto e, assicura Platina, colui che riuniva la tradizione medievale e un’elegante ricerca di equilibrio che certamente attirava gli umanisti dell’epoca.

Eleganza ed equilibrio? Che dire dei cinghiali e dei pavoni? Ebbene, Platina scrive che nel XV secolo e nel XVI le cose eranp un po’ cambiate. Nel ‘500 gli chef diventano più indipendenti e creativi, tendono a seguire meno i modelli preesistenti e più la propria ispirazione creativa: da allora non sono cambiati molto, se ci si pensa. Quello che è cambiato, però, è il modo in cui lavorano e dove. Mentre gli chef più popolari di oggi sono professionisti che gestiscono le proprie attività, i Gordon Ramsays e i Massimo Bottura del Rinascimento erano alle dipendenze di re e papi: gestivano le loro cucine, preparavano i loro banchetti e, possiamo scommetterci, probabilmente ogni tanto venivano anche rimproverati, se le loro creazioni erano considerate mediocri.

La cosa interessante, però, è che nel Rinascimento Gordon e Massimo avrebbero potuto lavorare insieme nella stessa cucina, cosa improbabile al giorno d’oggi: infatti, la cucina di un re o di un Papa avrebbe avuto più di un capo cuoco, responsabile della gestione del lavoro e dell’organizzazione dei piatti nelle diverse settimane. Tutti avevano la stessa autorità e potevano ricevere aiuto l’uno dall’altro durante le settimane in cui erano in carica.

Venendo al loro stile di vita, sembra che in realtà venissero trattati abbastanza bene; il loro signore aveva il dovere di fornire loro vestiti nuovi almeno una volta all’anno, avevano diritto ad una camera da letto privata con un letto (non necessariamente dato ad altri lavoratori del palazzo, che potevano dormire su cumuli di fieno), candele e legna per il fuoco durante la stagione fredda, nella stessa quantità a cui avevano diritto i gentiluomini (signori, o membri della borghesia).

Quando avevano fame, potevano certamente mangiare molto: avevano diritto a 1 kg di pane e quasi tre litri di vino al giorno, anche in questo caso la stessa quantità usata per i gentiluomini. E che dire di carne, formaggi e altri alimenti? Purtroppo le fonti non sono così chiare su questo, tuttavia, sappiamo che nelle corti più importanti d’Europa ai capocuochi venivano concessi circa 2 libbre di carne (vitello o gallina, a seconda di quello che c’era sul menù per il loro signore in quel giorno). Questo era, naturalmente, per i giorni normali: in quelli che in italiano chiamiamo i “giorni di magro”, cioè quei giorni in cui la carne non viene consumata nel rispetto dei precetti religiosi, gli chef ricevevano 8 uova al giorno, in sostituzione della carne. Durante la Quaresima, invece, venivano dati loro due chili e mezzo di pesce.

I grandi chef, che lavoravano in corti importanti, poi, avevano una vita piuttosto piacevole, almeno per quanto riguarda il cibo e l’alloggio: naturalmente, il loro lavoro doveva essere estenuante come lo è oggi, quindi diciamo che se lo meritavano. Ma i signori del Rinascimento erano generosi anche con i loro aiutanti, il nostro moderno staff di cucina e con i panettieri privati. Anche loro avevano diritto alla propria camera e a letti e ricevevano la stessa quantità di pane e vino del loro capo, anche se la qualità del vino non era la stessa. Erano garantite anche 1 libbra e mezzo di carne, di pesce – o 6 uova – al giorno. A quanto pare, i signori erano abbastanza desiderosi di trattare bene gli chef, i cuochi e il resto della squadra di cucina, in modo che fossero fedeli e, soprattutto, potessero sopportare il duro lavoro in cucina.

Anche se dipendente, il capo cuoco di un signore aveva piena libertà di assumere – e licenziare – il personale della sua cucina, e non veniva accettata alcuna interferenza da parte di altri membri dello staff di analogo rango.

Infine, ma non meno importante, un capocuoco doveva essere libero e in grado di viaggiare, e il suo signore aveva il dovere di assicurarsi che lo potesse fare. Perché? Semplicemente perché all’epoca la nobiltà si spostava spesso da un palazzo all’altro, un po’ come fa oggi Elisabetta II quando si trasferisce da Buckingham Palace in Scozia per l’estate. Naturalmente, ci si aspettava che il capo cuoco e il suo staff la seguissero, e dovevano farlo in tutta comodità e con facilità, nel senso che tutti avevano diritto al proprio cavallo, alle scarpe da passeggio e a tutto ciò di cui si ha bisogno per cucinare in giro.

E così, erano molto importanti, i nostri chef del Rinascimento: ben pagati, ben nutriti e molto rispettati. Mi chiedo se alcuni di loro, oltre al citato Martino da Como, abbiano mai raggiunto lo status di superstar: probabilmente sì, ma i loro nomi si devono essere persi nelle notti dei tempi.