When you contemplate a fly on the wall, I doubt that you ever imagine that fly reporting back what it has seen and heard. You know, chin-wagging about the goings-on of a body politic, dishing on gossip, scandalmongering. I doubt, too, that you ever imagine the wall being the one—er, the thing—doing the talking.

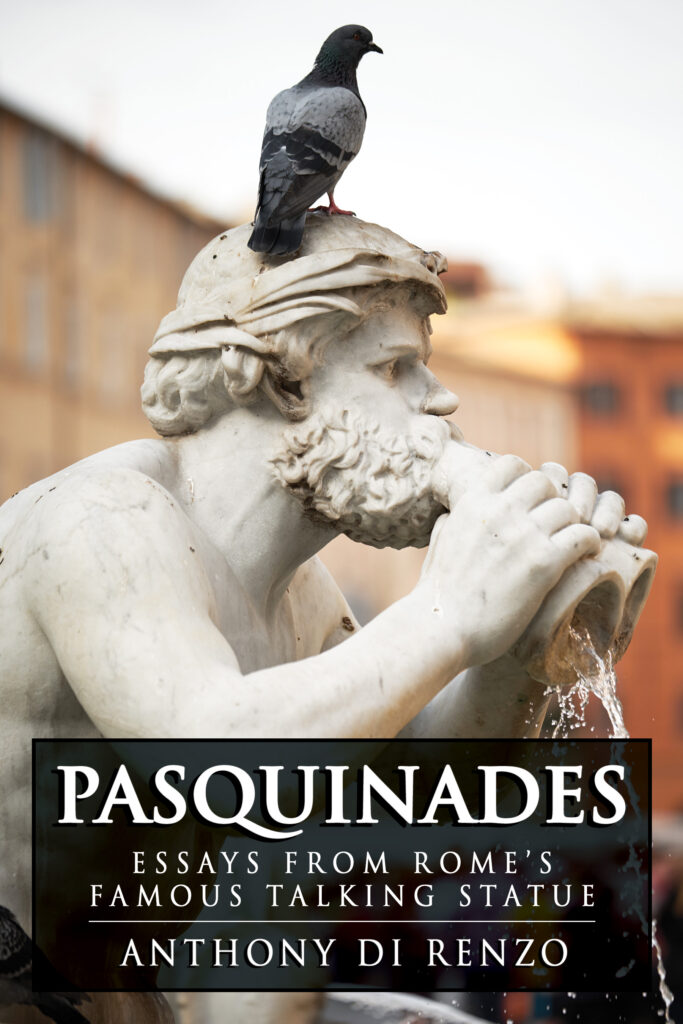

Such might be deemed the conceit of Anthony Di Renzo’s book, Pasquinades: Essays From Rome’s Famous Talking Statue. The hook is that the infamous talking statue, Pasquino, is put forth as some cross between flesh and stone, with the historical vantage of one endowed with a Janus Face and the rhetorical verve of a ventriloquist. From the days of Roman antiquity through the Renaissance and into the present day, Pasquino stands as a participant observer. As portrayed by Di Renzo, he is a maestro of wit and wisdom who embodies the rhetorical tradition of laying bare the hearts and minds of those who give voice to the popolo by jotting down squibs, posting them on the statue’s figure, and thereby devising a mouthpiece for comedy and commentary on princes, popes, politicians, and more. From the first, this makes Pasquinades an ambitious book. After all, it traverses time and space to account for everything from the waning days of the Roman Empire to the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, or perhaps as such, to read Pasquinades is to delight in the prose of a graven image with first-person omniscience. At times, the book comes off as fictionalized travel writing. At other times, it is belles-lettres qua cultural anthropology. At still other times, it is a written record of folk stories and oral histories. The point is that pasquinades are Di Renzo’s source material for what amounts to a narrative of the Eternal City that is, as profound as it is, in parts quite capricious. And it is crafted such that “bilocation” (16), or the ability to be in two places at once, is not only a characteristic of a personage whose situation is, well, figuratively set in stone. It is also the quality required for readers who will suspend their disbelief in order to embrace the deep recesses of Roman sensibilities that leave their marks on the surface features of everyday life.

What is abundantly clear is that Di Renzo imagines himself at once documenting this monument to mockery, Pasquino, and carrying on the dual notion that “eternity” is about endurance as well as whatever attaches itself to a certain age. A pasquinade, on its own, is ephemeral. A principle of vox populi vox statuae—that, in this case, is timeless.

So it is that we find in a single essay tales of papal taxation during baroque times folded into early-twentieth-century flirtations with fascism and, ultimately, traffic problems resulting from the degrado (Pasquino’s word for infrastructural degradation) in the present day. In another essay, lines are drawn from the sacrificial rites of ancient animal slaughters to the use of saffron in savory dishes, and then again to the sacrament of a coffee drink from a prominent shop near the Trevi Fountain. Across each and every essay is an impression that Pasquino is a material embodiment for historical witness, but hardly without strong opinions, i.e., his preference for “the splendor of Renaissance patronage” over “the sleaze of modern capitalism” (127). Coupled with this estimation, though, is a playful equivocation about just who is the talking statue. Once, a “limbless trunk with a ravaged face” (41). Thence, the man, the myth, the legend of his namesake, bellied up to a bar, sipping a Campari and soda, or ordering an espresso while recollecting the similarities between Margherita of Savoy and Diana Princess of Wales before raising a demitasse to toast their memory while watching steam rise “to heaven like incense” from the tabernacle of a moka pot (117). This man could be compared to nineteenth-century poet, Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, with whom the statue claims to have comported and who shared an affinity for the “rough-and-ready street language of lopped syllables and double consonants” over anything akin to pontifical pomp and circumstance (30). In these and so many other instances, we find insight into the people that live by Pasquino, that live in the aura of Pasquino, and who give Pasquino life.

Hence why the style of Di Renzo’s writing is so much like his subject matter of sections on “Festivals and Seasons,” “Papal Indulgences,” “Last Judgments,” etc., weird and wonderful. There are politics and culture in the winds of time, which is evidenced by a blusterous phenomenon that swells from the Sahara desert and blows across the Mediterranean Sea, the so-called scirocco. When the winds come, and in their wake, there arises a civil religion whereby meteorology trumps morality (56), not unlike how an epic blizzard once upon a time buried the Piazza del Popolo in snow and compelled the people to consider the power of cosmic forces alongside the machinations of mere human beings. Hence why Pasqunio looks for a divine spirit in what is brought down to earth. He sees in the paradoxes of those who live in the city, profit from its industries, and then take advantage of Ferragosto, a summer holiday that inspires affluent Romans to leave the city and get away from the daily grind. Simultaneously, those of the humble classes, the modern-day plebians, the people who really are the city, take “staycations” and visit the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and the gardens on the Pincian Hill. He sees it in his “Congregation of Wits,” or congress of other talking statues, who are in on the joke that we all live in a “world of ruins” (85). Accordingly, Pasquino is at home being in cahoots with, say, Michelangelo’s Moses, whistling at women instead of figuring a way out of Rome’s persistent “Madonna-whore complex” (140), just as he is at home being the spokesperson for the earthly contradictions of our lived conditions, waxing poetic about the makings of war and peace, and watching with a mix of admiration and despair the wiles of white doves, of “ecclesiastical buzzards,” of “human crows” (141–142). No surprise, then, that Pasquino pauses at one point to imagine what might happen to his heritage as face-to-face interactions give way to the signs and sounds of exchange mediated by smartphones (61). Tutto passa, indeed.

There is much to take away from Pasquinades. Here and there, some silly turns of phrase distract from otherwise elegant writing, to be sure. But what one gleans is the fleeting nature of both Old World orders and new ages. The humanity within and beyond the rhetoric of things. The meaning of a living record. With regard to Rome in particular, what Di Renzo has written is a portrait of national character that could pass as part of Ovid’s metamorphoses, anno Domini—pious and defiant, sentimental and insouciant, the paradigm case for ars longa, vita brevis. And what he seems to imply is this: when in Rome, live as Pasquino does.

In the epilogue is an invitation to bid Rome (and Pasquino) adieu by considering how Johan Wolfgang von Goethe became so inspired. This impassioned, introspective writer found himself immersed in an Italian journey and, when in Rome on the days from “Fat” Thursday through “Shrove” Tuesday, took to marauding in the streets, mocking magistrates, flirting with men and women, joining parades, and generally availing himself of the Eastertide Carnevale.

Of course, the invitation from Pasquino is to carry out this consideration with him, at Cecere’s, a gelateria near the Piazza di Trevi. I myself have not journeyed like Goethe. I have, however, been to Rome, and enjoyed gelato from Cecere’s. My wife and I were visiting in May of 2019, only months before the COVID-19 pandemic. Aside from the general ambiance, and what Pasquino describes as the joy of “smelling the fragrance of the potted rosemary, boxwood, and olive trees and listening to the distant roar of the fountain” (258), what stands out in my memory is a soft but discernible buzz of laughter. Everyone, it seemed, was smiling and laughing. I can almost conceive the mouth of Carrara marble on the face of Oceanus moving to reflect the aura of mirth, cutting a figure of abundance and health. At the very least, I can take from Di Renzo the idea that Pasquino represents the madness and folly, the ridiculousness and the sublime, that Goethe discovered. Pasquino empowers anyone to be a fly on the wall. The essays in this book are nothing if not affirmations of this representation, but only if Pasquino is as much talking statue as tour guide of lived history, even—or, especially—in times new Roman.

Chris Gilbert has a PhD in Rhetoric from Indiana University Bloomington. He is the author of Caricature and National Character: The United States at War (Penn State University Press, 2021) as well as numerous articles on comedy, humor, and rhetorical culture, for instance, “If This Statue Could Talk: Statuary Satire in the Pasquinade Tradition.” His most recent manuscript, When Comedy Goes Wrong, is in process.