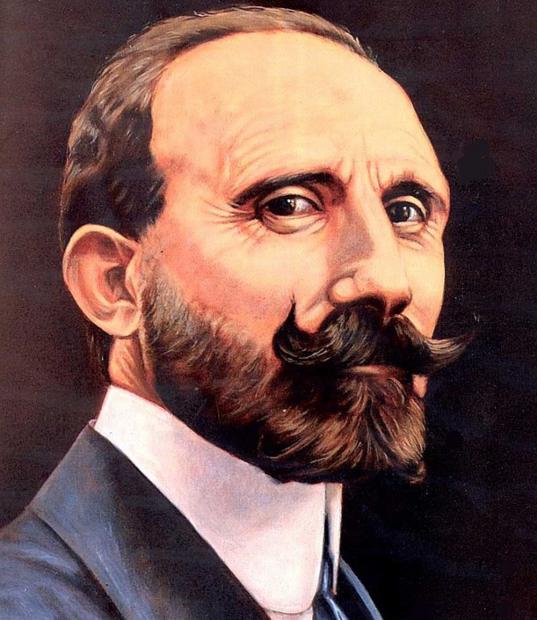

Nino Martoglio is universally acclaimed in Sicily as a figure larger than life. He excelled in many activities and by the time he died at the age of fifty, he was one of the most famous Sicilians of his times.

His contributions to the development of a Sicilian-language theatre are paramount. His activities in this field justify the claim that he was the real founder of the Sicilian theater and certainly its most enthusiastic promoter. As playwright he authored some of the most memorable Sicilian plays of all time, creating unforgettable characters such as Don Cola Duscio of L’aria del continente, a play that was translated and adapted for the American stage by Lou Cutell and Tino Trischitta with the title The Sicilian Bachelor, and Messer Rapa of I civitoti in pretura. In his relatively brief career he wrote numerous plays, and staged them with such success that they are classics of the Sicilian theater. Martoglio also discovered actors who became stars. The legendary Angelo Musco, Giovanni Grasso and Rosina Anselmi, to name but three of the most widely known, owe much of their fame to Martoglio. They in turn found in Martoglio’s characters congenial vehicles for their talents.

It was Nino Martoglio who convinced Luigi Pirandello to write for the theatre. Martoglio and Pirandello developed a close friendship that eventually led them to write two Sicilian language plays together: A vilanza (Cowardice) and Cappiddazzu paga tuttu, (Capiddazzu Pays for Everything). But at the beginning, while Pirandello experienced much critical resistance to his innovative and revolutionary work, Martoglio was a well-established playwright and literary entrepreneur.

He also achieved a measure of success as a movie director. In 1914 he became the artistic director of “Morgana Films” and was responsible for producing and directing some excellent movies. His Sperduti nel buio, (Lost in the Dark), was deemed a masterpiece by those who saw it. Unfortunately no prints have survived, but historians consider it a forerunner of Neorealism.

Martoglio was also a journalist and newspaper editor. At the age of 16, he founded his own newspaper, naming it D’Artagnan, after the character from The Three Musketeers of A. Dumas and published it from 1889 to 1904. He achieved fame for his humorous sonnets and for the biting satire with which he attacked the pomposity and corruption of his fellow Catanesi. While his biting criticism endeared him to the people of Catania, for whom Martoglio had a special affection, it created a number of problems with others. He fought duels with twenty-one men whose psyches he had bruised, risking injury and death. The D’Artagnan was written entirely or nearly by Martoglio under various pseudonyms.

If the theatre became his life after 1904, his love for poetry was the guiding light of his existence. And he loved Sicilian poetry in particular. He was the first person to organize a national convention on Sicilian poetry and wrote poetry only in Sicilian; a language he considered “ammagaturi” (“bewitching”). Many of the poems later collected in Centona first appeared in the D’Artagnan. In fact, as the reputation of the newspaper grew and attracted the most famous and talented dialect poets and writers of his time, such as Pascarella, Trilussa, Di Giacomo, Fucini and others, Martoglio’s reputation as a poet also crossed the straits of Messina into the mainland, and grew to the point that Giosuè Carducci, the first Italian Nobel Prize winner for literature wrote:

“Nessuno ha il diritto a dirsi letterato, che non conosca il linguaggio del Meli ed in esso linguaggio i sonetti del Martoglio.” (Nobody has the right to consider himself a literary person if he does not know the language of Meli and in that language the sonnets of Martoglio.)

In spite of his many accomplishments, in the theatre, in poetry, as a journalist, and as a theatrical and movie director, Martoglio has received scant critical attention.

Italian literature specialists have not shown much critical interest in Martoglio. Very little has been written about him since his death. In the dialogue between himself and the personification of his book Centona, which serves as a preface to the work, the poet complained that the “varvasapi allittricuti” (literary big-wigs) had not given his poetry the recognition it deserved. Martoglio claimed, however, that while the academicians had not made a fuss about his work, the people had consistently displayed affection for it, so much so that he can say that “there isn’t any town in Sicily where Centona has not brought people cheer.” Martoglio went on to say that his poetry was a favorite of the Sicilian people wherever they may be, in Sicily, in war trenches and in foreign lands. The reason for this predilection is that his poetry brought people the smells and sounds of Sicily, the passions that are always raging in their unhappy hearts, and the memories of their beloved and tragic land. Martoglio concluded with a beautiful testimony to his poetry that says:

As long as you leave on each street you pass

of restless Sicily the scent and soul,

you’ll always be assured of great success.

While some readers may regard this as wishful thinking, I can testify from personal experience that it is actually true. Sicilians love Martoglio and his poetry. One brief story will make the point: I was browsing one day in the Cavallotto bookstore in Catania, looking through their Sicilian poetry section and started a conversation with Rosario Romeo, the store manager. When I told him that I was translating Centona into English (eventually it was published as The Poetry of Nino Martoglio, Legas), he began to recite “Lu cummattimentu tra Orlandu e Rinardu” from memory. He went through nearly 8 stanzas of the poem without faltering once, showing great appreciation for Martoglio’s cleverness. His wonderful performance, however, was not all that extraordinary. In fact, on several occasions, on learning of my interests in Sicilian literature, my interlocutors have begun reciting their favorite poems. As it happens, the poets most commonly found in such personal repertories are Giovanni Meli, Micio Tempio, and Nino Martoglio.

Martoglio was much loved in his adoptive city. The people of Catania identified with his characters in one way or another, they recognized their own weaknesses and ignorance in the people he created. In his poems they heard every day voices; they saw neighborhood women gossiping at their windows; they heard echoes of the street vendors’ voices, mothers calling children for supper, a lover urging his beloved to come out on her balcony. Martoglio is an embodiment of Sicily and Sicilian sensibilities. Pirandello was right when he said that Martoglio was, after Giovanni Meli, the most expressive poet of Sicily. In his preface to Centona Pirandello said that Martoglio was for Sicily, “What Di Giacomo and Russo were for Naples; what Pascarella and Trilussa were for Rome; Fucini for Tuscany; Selvatico and Barbarini for Venezia…. Martoglio embodies all his Sicily, the Sicily that loves and hates, that laughs and weeps and frets, using accents and a manner that here in Centona are incomparably expressed.”

Martoglio indeed expressed the varied aspects of Sicilian life. He sang about many things and always with freshness, ingenuity, inventiveness and truth: he sang of macho Catanese men who live in taverns where the light of the sun never shines and who speak a jargon so obscure that only God and Martoglio could fathom, of people in the rough Civita neighborhood where he recorded the imaginative insults of neighborhood women whose linguistic skills display the astuteness and subtlety of a master politician; he captured with uncanny subtlety the skillful verbal exchanges between two partners playing “briscula” and painted vignettes—“tranches de vie”— like the sonnet “A Cira,” which Pirandello rightly considered a little masterpiece in which one word, one gesture or one look magically discloses a world of complex motivations and emotions.

If I were to name one theme that is ever present in Centona, it would be love: love as the principal reason for human life, love as the source of bitterness and pain; love that is bought, love as the source of all ecstasy, love that is full of thorns. And the “fimmina” (woman-female), which in Sicilian is not an offensive word as it is in Italian, is always on Martoglio’s mind. At times she is an angel that recalls the Angel-like women of the “Dolce Stil Novo”; at times she is the temptress who leads men into hell and gives them death when she tires of them. Women are the source of all the sweetness in the world. The only problem is that he can never be sure how long a woman’s promise will last. Inevitably they abandon the poet, they betray and forsake him.

Martoglio seems to search for an ideal of constancy that he can never find, except in the image of the saintly mother. The image of the “donna-danno” (woman/ harm) is, in fact, frequently opposed to that of the mother, who alone is able to understand and comfort the poet.