On November 2, 1975, the Italian intellectual, poet, novelist, filmmaker – in a word: Artist in capital letter – Pier Paolo Pasolini, was brutally murdered in Ostia, coastal area near Rome. Forty years later, the Italian Cultural Institute in L.A., remembered the tragedy, demonstrating how much this iconic personality is still deeply rooted in our collective memory.

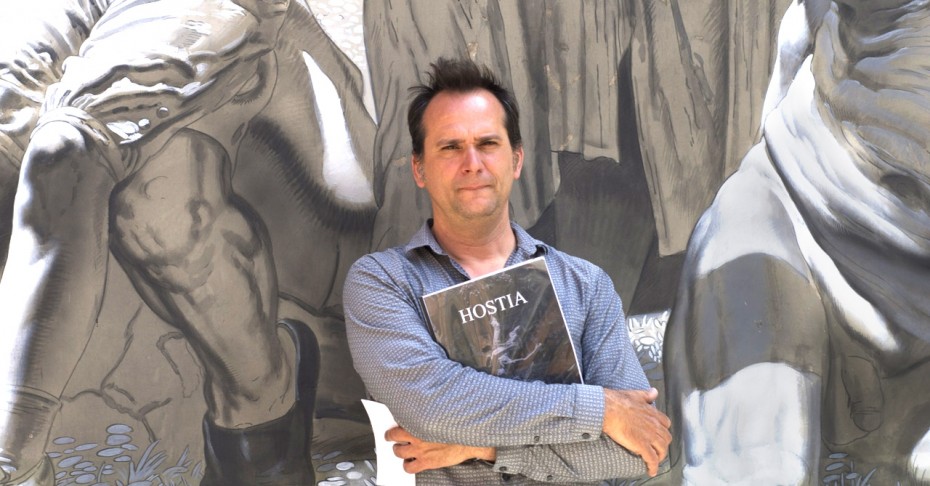

Following a compelling conversation between LA-based artist, Nicola Verlato (a native of Verona), author of Hostia, an ongoing figurative tribute to Pasolini, and Gian Maria Annovi, Assistant Professor of French and Italian and Gender Studies at USC, I’ve had the wonderful opportunity to chat with Nicola, thus further exploring his fascinating aesthetics.

In your bio (see: www. nicolaverlato.com), it stands out how your painting and musical talent emerged precociously. What role did your parents play in your approach to these arts?

Both my mom and my dad fully supported me, as a child, in the pursue of my passions. On my father’s side, there was a certain artistic tradition, particularly pictorial: in fact my dad used to paint during his youth, and other relatives approached painting as well, although erratically.

My household had a huge collection of art catalogues and books. To date, I still feel in debt towards those precious volumes, which gave me the earliest figurative imprint.

On the part of my mother, whom I’ve always been very attached to, there has constantly been a more active support, almost as if she was projecting her dreams and aspirations onto me. My mom has always seconded me, despite some apprehension, even in my most “reckless” ideas, such as dropping out of high school and start studying lute at the Conservatory in Verona.

Tell us about your figurative formation at the Franciscan friar, Fra’ Terenzio’s atelier. What would you define as the biggest lesson during that time?

That time of my life was extremely happy. Despite being merely nine years old, when I started to attend Fra’ Terenzio’s atelier, finally I had found a place, where I was able to acquire the first solid foundation to take up my own projects.

My training used to be rather strict. The fact that I was just a child, was not taken into consideration at all. However, that was exactly what I wanted, that is to learn drawing and painting, with no shortcuts on the ways to apprehend their secrets.

I was lucky enough to experience a world, which perhaps does not exist any longer. Back then, if you showed talent, you were immediately called to partake in a sort of “parallel society”, with no distinction between children and adults, but only followers of the cult of art and its great masters.

In the musical field, your education at the Conservatory in Verona, appears to be more conventional. Did you have a mentor, or did you make there any fundamental encounter for your future career?

My instructor was Orlando Cristoforetti, whom I have always held in high regard. He impressed me both for his almost ascetic and highly intellectualized attitude.

However, his lute’s class had nothing conventional, at all. Our teacher brought us microfilms’ copies of musical manuscripts, whom nobody had ever executed for four or five centuries, and he assigned us those pieces, for whom no recordings existed.

We had to “fumble” around, by experimenting either Albutio’s Fantasias, or Marco Dall’Aquila’s ones or G. G. Kapsperger’s pieces. Indeed, back then, during the 80’s, that was still a pioneering field.

Today, there are plenty of recordings available and it’s great to see how some of those pieces has entered the repertory.

Similarly to your case, Pasolini, endowed with multiple talents (including painting itself), launched himself into the artistic activity, when he was seven years old (he approached poetry, while, in your case, painting). Let’s dig more deeply into your figurative series on the Italian intellectual. Which, among Pasolini’s facets, inspires/ attracts you the most?

First of all, thanks for your comparison. As a matter of fact, my series on Pasolini is part of a big project – which has been going on in the last five or six years – and structures itself around the plan for a monumental and utopian building, or “mausoleum”, to be built in locations relevant to the “media stars”, whom I’m interested into.

In this specific case, the idea is to erect a mausoleum to Pasolini, in the exact area in Ostia, where he was murdered.

The monument is going to feature sculptures, paintings and frescoes, whom I’ve been developing in the last two years, together with the architectonical project itself. I’m also composing a series of dedicated musical pieces for orchestra.

What has particularly impressed me about Pasolini’s figure, is his tragic sense and his prophetic consciousness about the loss, whom a country like Italy – with its incredible cultural identity – would have inflicted to the world, depriving it of the opportunity of redemption in the art itself.

I was impressed by one of your sentences, during your conversation at the IIC: “When you discover a form of art so early in your life, you remain attached to that for the rest of your life.” Could you expand on that?

Around the age of seven, every child learns about his/her own mortality, but, at the same time, some children discover its “antidote”: art and, through it, a promise for immortality.

In those children’s minds, it unfolds a world which portends an infinite power, to be fulfilled exclusively through that form of art to whom they are inclined the most.

As they grow up, when they find out how the society they live in, the “modern world”, doesn’t care about art anymore, then it originates a drama, which can either find several alternative solutions, or never be resolved.

That person will always be someone, deprived of something essential, that is his/her own heart.

For me, Pasolini is the perfect embodiment of that tragedy. In fact, art is doomed in the modern times, for it is marginalized in a state of total irrelevance.

Tell us more about Pasolini’s Mausoleum, whom you’re carrying out in Ostia. Aside from that, are you simultaneously working at other projects?

For two years, I’ve been working at the Mausoleum. I’m constantly creating new paintings, musical pieces and sculptures, which are going to be reassembled differently according to the space constraints, dictated by the various exhibition’s venues across Italy. Sooner or later, I hope to be able to encompass this large project in a book.

In ten days, I’m leaving for Rome, to paint a new mural in Ostia. The ultimate goal is to build the actual monumental building, either in Ostia or in Bologna (Pasolini’s home town).

I’m simultaneously working at several other projects, such as next year’s exhibition, at the Long Beach Museum of Art, focused on Michael Jackson. It is going to follow the same criteria: Mausoleum, painting, sculpture and music.

Obviously, the two artists are completely different, but I’m highly interested in the way the musical legend shaped his own life.

You experienced both the East Coast, living in New York City, and currently live in L.A. In your opinion, what are the strong points in one and the other?

To me, New York City looks old and too much tied to its past. It suffers from the same “disease”, which we find in Europe, without having produced anything in any field, even close to what the Old continent has created.

Los Angeles is a lot more open culturally and it captivates me to a greater degree. The fact that this city is one of the most prominent entertainment center in the world, if not the absolute top, makes it very interesting to one like me, who constantly investigates mythological narratives and the mechanisms behind those.

Do you have contacts with the Italian-American community in L.A.? For example, do you attend the local Italian Cultural Institute or similar organizations?

Yes, I do. In such a spread out city like L.A., the IIC plays a predominant role in bringing together the members of our community. Aside from other figurative artists, I’ve had easily access to personalities, working in the movie industry, musical field, in the scientific sector, or even in the 3D modelling.

My other acquaintances and friendships with Italians, come from chance encounters, very often in coffee shops.