If there ever was an honorary Italian, it must be Bay Area author Dianne Hales. Although the majority of her career has centered on health topics and textbooks, Hales published La Bella Lingua in 2010, a personal memoir encapsulating her 25-year pilgrimage to speak Italian, to impressive reviews. Her latest book, Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered, can’t be relegated to a sophomore effort for the experienced writer, but it is the second contribution to what is quickly becoming the Italian series in Hales’ body of work.

Mona Lisa is equal parts history, biography, and reimagining of the flesh and blood woman in Da Vinci’s masterpiece, Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo. Hales was brought to the subject of Lisa Gherardini while studying at the Istituto Dante Alighieri in her quest to speak Italian—news pieces were being printed at the time on the findings of Mona Lisa by expert Giuseppe Pallanti that somehow spoke to Hales, and she began casually clipping articles. Then, one evening over dinner at a friend’s home, the host happened to mention that Lisa’s mother had once lived in the very same building. Suddenly, the idea of the image in the painting as mother, daughter, lover, friend, a woman who really lived—una donna vera—hit home.

Calling Lisa “Florence’s most famous daughter,” one of the fascinations about the enigmatic woman in the painting for Hales was the irony of her obscurity: How, in the most romanticized region of Italy, where plaques adorn every piazza and honor even marginal historical events, is the life of the most iconic, mysterious face in the world not recognized? Likewise, the place where this woman lived in Florence is now neglected, covered in graffiti, bearing no witness to the extraordinary events that took place so many hundreds of years ago.

Hales spent months upon months pouring over archival documents, traveling to Italy and the homes of Gherardini ghosts, and piecing together the relationships between Florentines to arrive at how Leonardo, whose father lived just blocks away from the married Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo, came to paint the famous beauty. As Hales describes, “I was struck by how close everything was together—neighbors, people knew each other. I don’t think she was a complete stranger; at least what she looked like was familiar to Leonardo.”

However, it’s important to note that the painter is mere subtext in this book, where the woman finally has her day. For Hales, one of the most important discoveries to emerge from her research is how important women truly were in the fabric of everyday life. “I started by reading a lot of academic studies, and the Seminist scholars were so depressing. Florence was one of the most unlucky places to be born as a woman.”

Indeed, in many books, perhaps American ones especially, women were little more than cattle, waiting to be sold off by their fathers, abused by their husbands, and then enslaved to the duty of bearing children. In what Hales calls a “happy surprise,” she found that Italian women can clearly be credited with the survival of the family when cities were under siege and in Lisa’s case, “she had a difficult husband, but one who doted on her. Women were the center of the family, and nothing is stronger than the family in Italy.“

Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered also spends ample time wading through the violent feudal past of one of Florence’s most notable noble families—a factor that Hales feels contributed to Da Vinci’s fascination with Lisa. After all, by the time Da Vinci painted Lisa, the once-powerful Gherardini faction had long since fallen. But, as Hales conjectures, “I think she had the spirit. And there was something in her that Leonardo saw—her Gherardininess.”

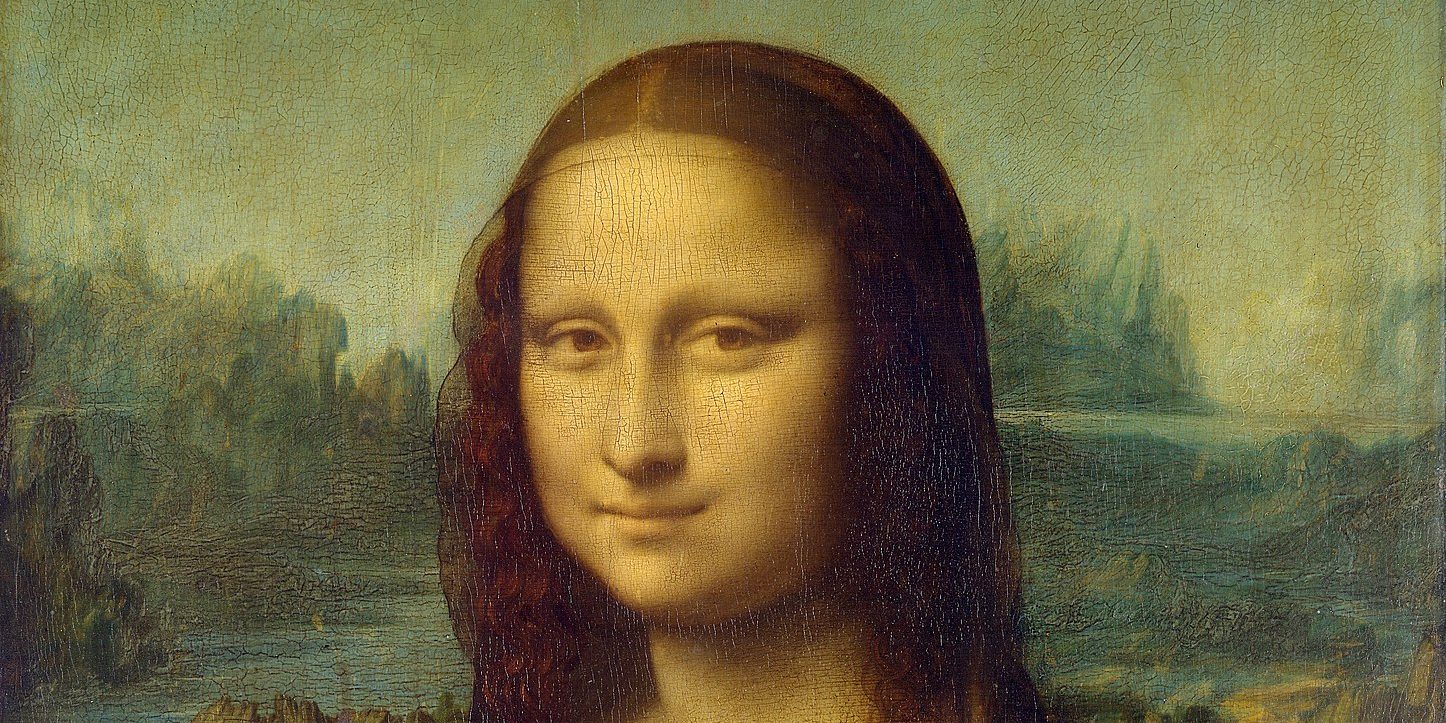

In turn, it was this spirit that Hales thinks is behind that infamous, indescribable smile. “Leonardo was a rock star. (Lisa) knew she was in the presence of greatness. Her smile—this is a woman who is very aware of herself, who is confident, who is sort of bemused by the whole situation. Leonardo kept the painting his entire life and worked on it; he matured her emotionally and intellectually.”

As to whether the book may influence the city of Florence to take more pride in its most legendary export, Hales is hopeful. “Last year for the first time, and this year again, they celebrated her birthday. As more people have come to think of her and know her name, Lisa Gherardini, I would love to see her get her due as a woman that has nothing to do with the painting. The French have sort of usurped pride in the Mona Lisa—I’d love to us reclaim her.” Spoken like a true Italian.