It has been just a few weeks since the Italian media coverage began to be monopolized by the success of the new TV series Medici: Masters of Florence starring Richard Madden and Dustin Hoffman. As it appears, the intrigues of the famous banking family which came to rule over Firenze for several centuries has attracted millions of spectators in Italy, and an even greater success is expected from the series’ upcoming release across Europe and in the United States. If you really want to get ready for the show, there is probably nothing better to do than taking a look at the traces left by the House of Medici in Florence. In this regard, even though the whole city abounds in all kinds of references to them, no place is as closely related to the family as the chapels in San Lorenzo where most of its prominent members were buried. Let’s step inside the Cappelle medicee and visit this powerful dynasty’s stunning mausoleum.

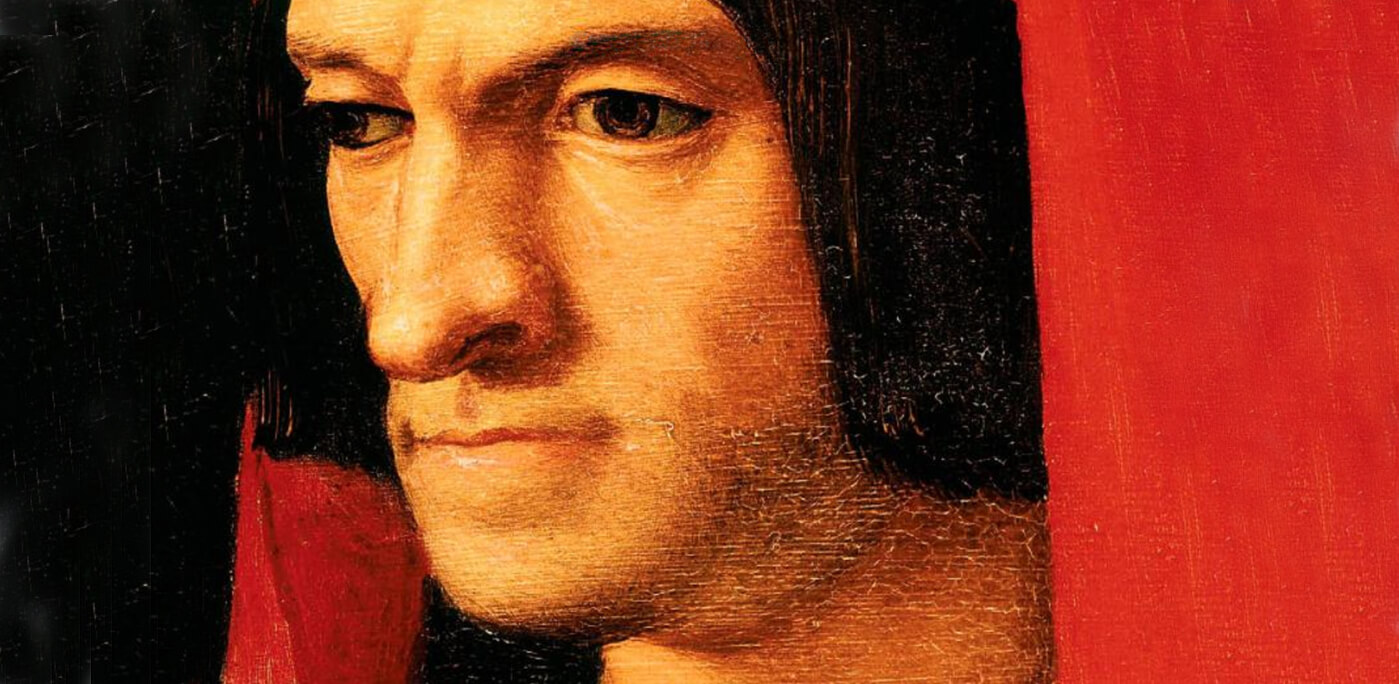

The first thing you notice in approaching the magnificent dome of the 59-meter-high building housing the Chapels is that it is actually part of the Basilica di San Lorenzo. This church, one of the oldest in Florence, happened to be the parish church of the Medici, who in the 15th century decided to finance its rebuilding under the direction of the master Filippo Brunelleschi. But even though San Lorenzo then began to look more like it is nowadays, the church was completed only well after the artist’s death: one of the major additions was given precisely by the Medici Chapels, obtained by an extension of the basilica’s apse. It was because of two popes, Leo X (aka Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici) and Clement VII (aka Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici), that the idea of making this place the burial site of the Medici family first came out.

The main entrance to the Chapels, a state museum since 1896, is located just under the dome at the back of the church: from here, you find yourself walking into the vaulted underground portion known as The Crypt. Alongside the tens of tombs to be found all over the floor, this room also showcases a variety of interesting artifacts, some paintings portraying the Medici, a large bronze sculpture representing the princess that was the last lineal descent of the family, and – above all – a whole set of precious reliquaries (most of them quite scary, for that matter).

However it may be, it is only by climbing the stairs to the marvelous Cappella dei Principi (Chapel of the Princes) that one gets a clear impression of what is most glorious about this place: its octagon-shaped interior, including the finely made cenotaphs of six Grand Dukes of Tuscany with dedicatory inscriptions, is entirely covered in dark marble and gemstones. But if that weren’t enough, the view of the scenes from the Bible painted by Pietro Benvenuti on the cupola above, or the flooring of semiprecious stone inlay below, might as well take your breath away.

Even though the Chapel of the Princes was first conceived by Grand Duke Cosimo I, who entrusted none other than Giorgio Vasari with the project, the actual construction began only in 1604 under the Baroque architect Matteo Nigetti’s supervision: that’s one of the reasons why opulence and sumptuousness abound here. The walls of the Chapel are encrusted with as much as sixteen shiny coats-of-arms representing the most important cities of the Grand Duchy, while the six stone sarcophagi are each topped with a pillow sustaining the grand-ducal crown and with a large niche that was supposed to host a statue of the late Grand Dukes (only two of them, those of Ferdinando I and Cosimo II, were eventually completed). In addition, the rooms at the sides of the altar include other objects and relics that make up the so-called Treasure of San Lorenzo.

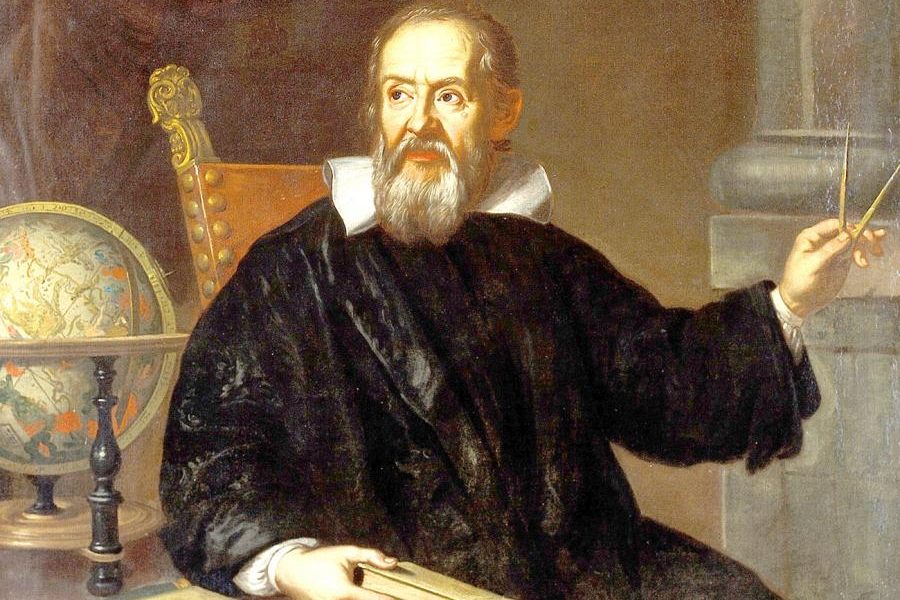

But there is even more to be discovered inside the Medici Chapels: as a matter of fact, the wing called New Sacristy (Sagrestia Nuova), that is the oldest extension of San Lorenzo’s apse, was created by the great Michelangelo in the 1520s. Under the coffered vault of this chapel, four more members of the Medici family rests. However, because of Michelangelo’s eventual departure for Rome in 1534, only the tombs of Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino and Giuliano, Duke of Nemours are now adorned with the artist’s marble sculptures, while those of the more famous Lorenzo il Magnifico (“the Magnificent”) and his brother Giuliano were never completed and are thus quite unremarkable. Nonetheless, you can still lose yourself in the incredible beauty of the two completed funerary monuments, one representing Night and Day, the other Dawn and Dusk: as the American poet Gregory Corso wrote during a visit to his parents’ native country, in the end “one is almost inclined to jump in one of them—and gloat in the eternal fix”.