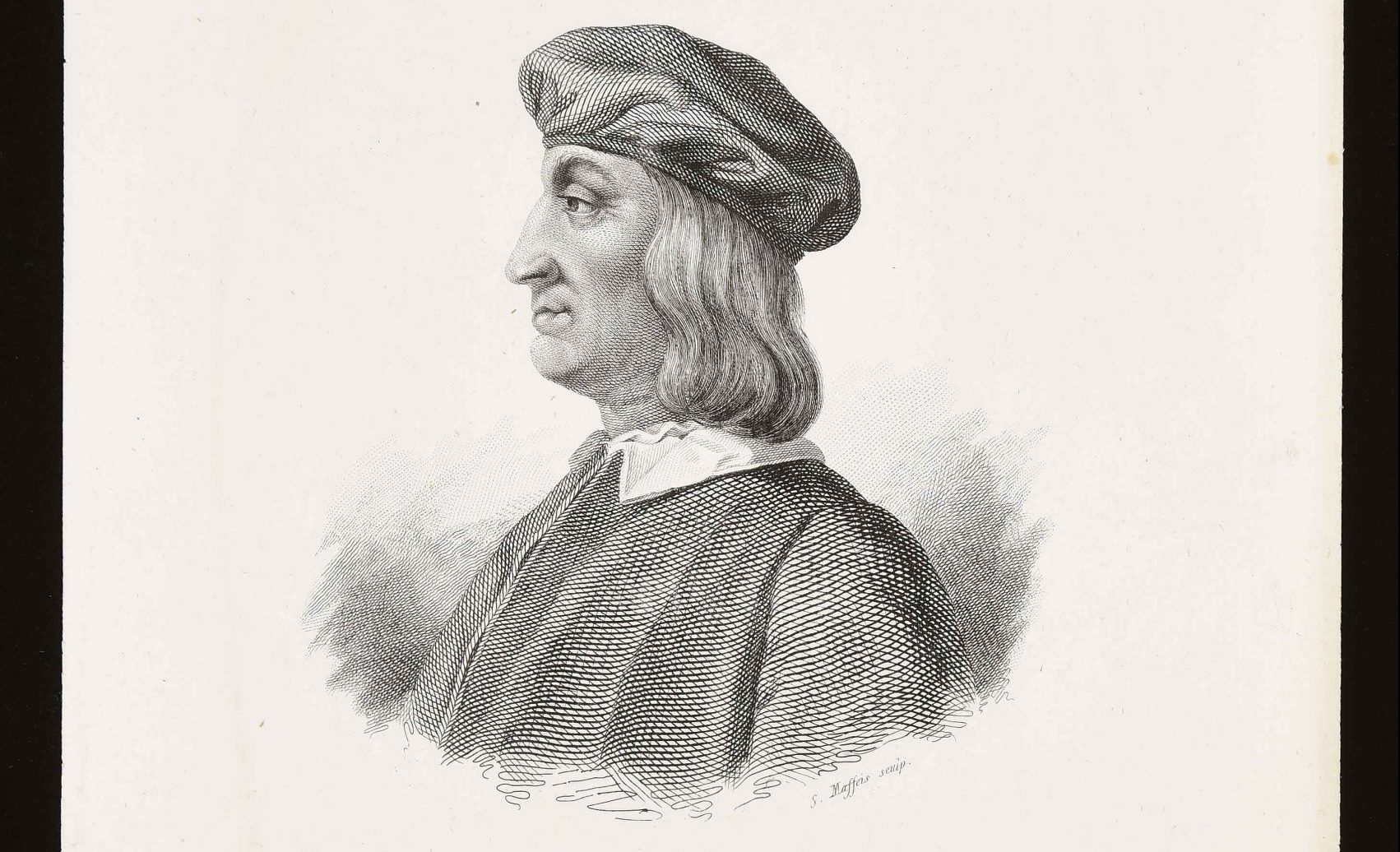

The name Aldo Manuzio is unfamiliar to most of us, though he deeply influenced history and, surprisingly, our everyday lives.

Aldo Manuzio is considered to be one of the greats of the publishing and printing trades. To mention just a few of his inventions, he created italic type, and was among the first to introduce inexpensive books in small formats bound in vellum that at the time were read much like modern paperbacks.

Manuzio was born in Italy in 1449 at the time of the Papal State in Bassiano, what is now province of Latina, about 100km from Rome. This year is the 500th anniversary of his death, February 6th, 1515.

As a contemporary of the Italian Renaissance, he was educated as a humanistic scholar, studying Latin in Rome and Greek in Ferrara. In 1482 he moved, with his famous friend and fellow student, Giovanni Pico, to Mirandola where he continued to study Greek literature.

His friend Pico introduced him to his nephews, Alberto and Lionello Pio, princes of Carpi. Aldo became their tutor. Eventually Alberto Pio decided to supply Manuzio with funds to start his printing press, Aldine Press, in Venice in 1490, which soon became an innovative and important printer of the Venetian High Renaissance.

The city by that time was not only a major printing center but it also had a large library of Greek manuscripts from Constantinople and a population of Greeks who could assist with their translation.

Manuzio’s greatest desire was to preserve ancient Greek literature, by printing editions of its greatest books. Before Manuzio, only four Italian towns had printed editions of ancient Greek texts, but among the many books printed only three were classics.

In order to pursue his dream in the most authentic way possible, he began gathering Greek scholars and compositors around him, employing as many as 30 Greeks in his print shop and even speaking Greek at home. Instructions to typesetters and binders were given in Greek, not to mention that the prefaces to his editions were written in Greek. Manuzio wanted Greeks form Crete to control all the printed manuscripts, read the proofs, and provide samples of calligraphy for casts of Greek type.

He also set up a definite scheme for book design, produced the first italic type commissioned to Francesco Griffo, introduced small and handy pocket editions of the classics called “octavos”, and applied several innovations in binding technique and design for use on a broad scheme.

Together with his grandson who was named after him, Aldo Manuzio the Younger, he introduced a standardized system of punctuation by defining our modern use of the semicolon and shaping the modern comma.

In 1501, Aldo began to use, as his publisher’s device, the image of a dolphin wrapped around an anchor. His editions were so highly admired and respected that the dolphin and anchor symbol was almost immediately pirated by French and Italian publishers. In the nineteenth-century the icon was adopted by the London firm of William Pickering, and by Doubleday. As recently as the late 20th century, an American software company in Seattle, Washington — Aldus (Aldo’s Latin name) – honored him by adopting his name.

Before the dolphin and the anchor, Aldo had begun to use the motto “Festina lente” (hasten slowly) after reading it on an ancient Roman coin issued during the reigns of the Emperors Titus and Domitian in AD 80-82, that Pietro Bembo gave him as a present. The motto refers to the combination of two important qualities: quickness and firmness.

Manuzio strove for excellence in typography and book design while at the same time striving to create inexpensive editions. He had to struggle against many difficulties including strikes by his workmen, piracy from rivals, and the interruptions of war.

Sadly, when Manuzio died in Venice in 1515 he was a poor man, yet his hard work safeguarded a place for ancient Greek literature among the world’s cultures.