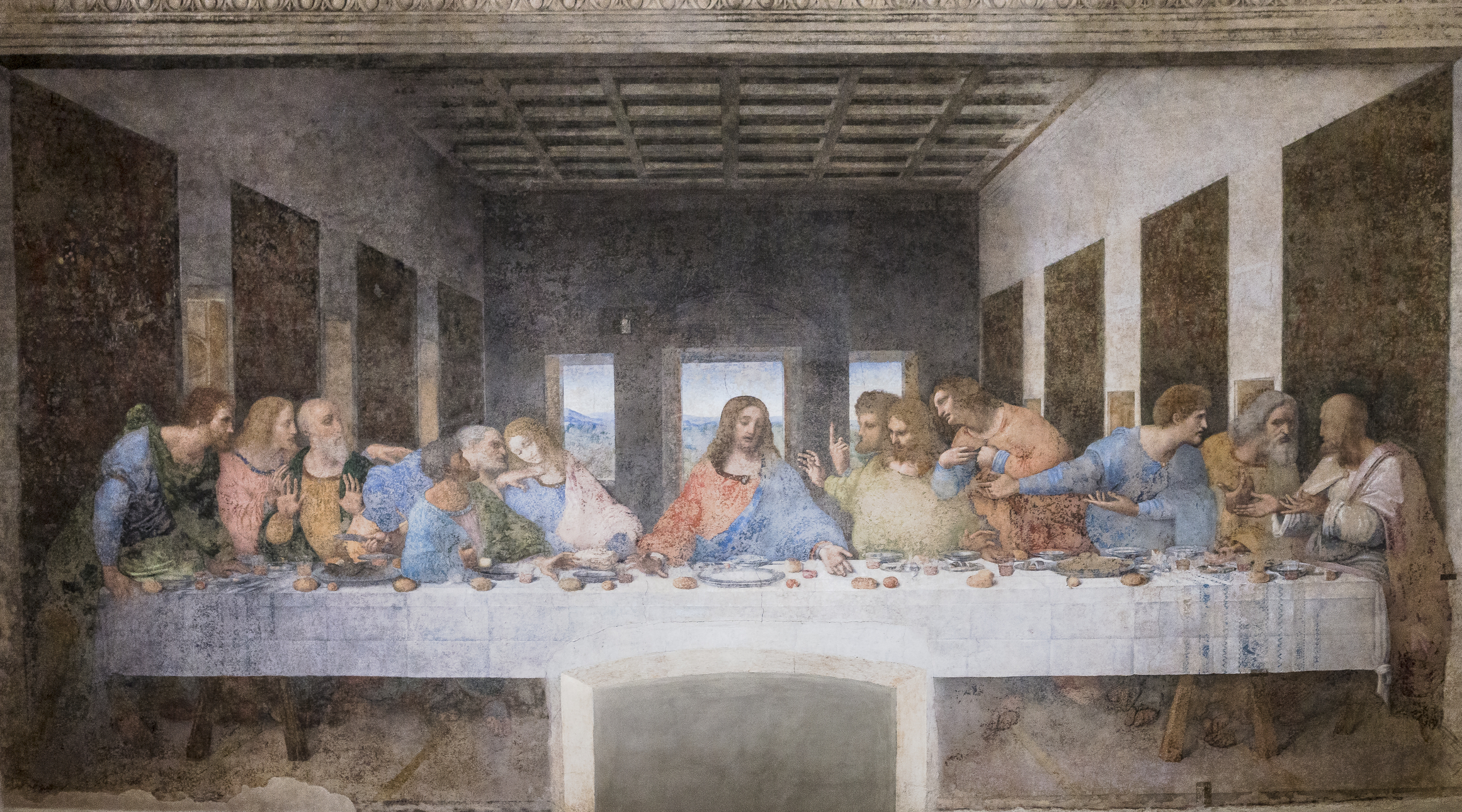

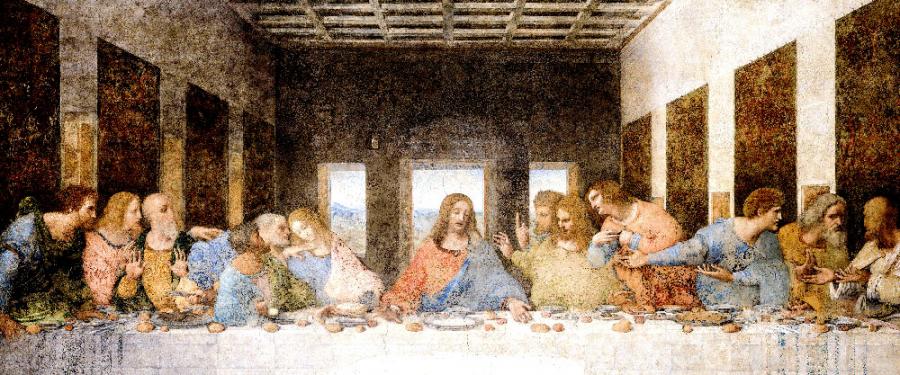

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is undoubtedly one of the most iconic, most famous works of art of all times. As such, it has always attracted crowds to the Refectory of the Dominican church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan where it is located. It is also regarded as a miraculous painting: it survived Leonardo’s own experimentations with a new faulty fresco technique, and subsequently survived rudimentary restorations throughout the centuries; then, during WWII, in August 1943, when allied bombings razed Milan and destroyed the church, this mural amazingly survived intact on the only wall left standing in the refectory.

Ever since author Dan Brown published his famous, or, for others, infamous book The Da Vinci Code, the crowds of people visiting this painting have exponentially increased. Tourists are now here not only to admire Leonardo’s art, but also to discuss, comment and guess who the figures represented in the painting are. Is there, or is there not, a woman at the right of Jesus?

As a Milanese, I have seen this painting so many times that I can almost see it with my eyes closed. But this time I am going to specifically focus on the hot controversy revolving around one figure, the one to the right of Jesus, the figure “in question.” In fact, many of the tourists who show up at the refectory have read Dan Brown’s book, and are here to look in person and give a verdict. It seems strange that Brown’s ingenious book has been taken seriously even in Catholic Italy, especially since the author himself stated that it is a novel, actually, a murder mystery, of the kind Agatha Christie wrote. The sites described in Dan Brown’s book have been the objects of fan pilgrimages, from the church of Saint Sulpice in Paris, to Roslyn in the United Kingdom. In Italy, the pilgrimage of curious tourists has focused on Leonardo’s Last Supper. This work of art was frequently and religiously visited by tourists even before Brown’s book came out. But now the crowds are enormous, the queues extremely long, and the eyes of the curious visitors seem to laser on the figure at the right of Jesus. Such are the crowds that one must book a visit way in advance, a visit that can only last 15 minutes at a time, unless you book a tour.

The last supper of Jesus and his apostles has been for centuries a cherished subject of painters. In his painting, Leonardo chose the most poignant moment of the event: the moment when Jesus announces to the apostles that one among them would betray him. With his sublime brush, Leonardo describes the reaction of each one of them.

Here I am again, this time trying to see what Dan Brown sees. Is the figure at the right side of Jesus a man or a woman? And if a woman, is this woman the one from the town of Magdala, Mary Magdalene? People in the crowd comment, discuss, argue. Certainly Leonardo was creative in the positioning of the partakers of the Last Supper, although he was faithful to the traditional iconography that featured twelve men sitting at a table around Jesus. Leonardo positions six apostles on one side of Jesus and six on the other side, all in different groups of three men per group. But Brown sees twelve men, including Jesus, and one woman, Mary Magdalene. Thus, at the right of Jesus, Brown sees a woman in what tradition had always identified as the figure of young Saint John, the young man with delicate features and with flowing reddish hair. Brown goes even further, and sees the shape of the letter M in the empty space between Jesus and the figure at his right, standing, in his opinion, for the word Matrimony. Also, Brown sees in the painting a very jealous Peter leaning menacingly towards Mary Magdalene (that is, young Saint John), pushing a blade-like hand across her neck. In the composition there is indeed a knife that appears to be held by a hand belonging to a disembodied figure, a knife fit to cut meat or to kill. But it does not seem to me to be Peter’s hand.

Brown purports to believe that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married, and had a daughter, from whom the French royal dynasty of the Merovingians stemmed. One legend tells that after Jesus’ death, Mary Magdalene moved to the South of France. Further, Brown claims that the famous Holy Grail is not a cup, but actually Mary herself, and specifically her womb, the eternal feminine element, the calyx containing the seed of life. Brown sees the suppression of Mary Magdalene’s pre-eminence in the life of Jesus as a church plot to eliminate that “uncomfortable” female element. Brown states that Leonardo’s fresco practically shouts that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were a married couple. Brown even points out that Jesus and Mary are clothed in inverse colors, Jesus in a red robe with blue cloak, Mary with a blue robe with a red coat: Yin and Yang. Brown also points out that the two figures appear to be joined at the hip.

I cannot see the figure at the right of Jesus as a woman, not by a stretch of the imagination. I see the figure of a delicate, if feeble, adolescent, a young man with long streaming hair, as young Saint John, “the beloved disciple of Jesus,” as he has been described in the Scriptures. Squint as I may, I do not see in his figure the “hint of a bosom” that Brown claims is there and that no one had noticed prior to the most recent restoration. Right behind me, a young couple are vehemently arguing in English; finally the woman, exasperated, exclaims: “It’s a man, stupid!”

Mary Magdalene got a bad rap. Her misrepresentation as a prostitute originated in the sixth century, in a homily by Pope Gregory the Great. The Pope actually intended to praise her for being a reformed sinner. But in those days (as in these days) there were so many Mary. He got the wrong Mary. According to the apocryphal tradition and the legend, Mary Magdalene evangelized Provence, the south of France. She is celebrated on July 22, and is traditionally represented as a beautiful woman with long flowing hair, holding a jar of precious unguent. She protects women sinners, gardeners and hairdressers, and stands as a symbol for contemplative life. According to the gospels, Mary Magdalene was present at the crucifixion and the burial of Christ (gospels of Mathew, Mark and John). Mary was the first person to witness the resurrection of Jesus. In fact, in Mathew and John, as well as in the appendix to Mark’s gospel, Mary Magdalene, not Peter, is the primary witness of the resurrection. And in my opinion, she does not appear in Leonardo’s Last Supper.