Just north of Spokane lies the tiny community of Clayton, Wash., population 443, founded in 1889 and named after the abundant clay deposits nearby. The town became home to the Washington Brick Company, renowned for its beautiful decorative tiles and terra cotta sewer pipes. Many of its craftsmen were Italian immigrants.

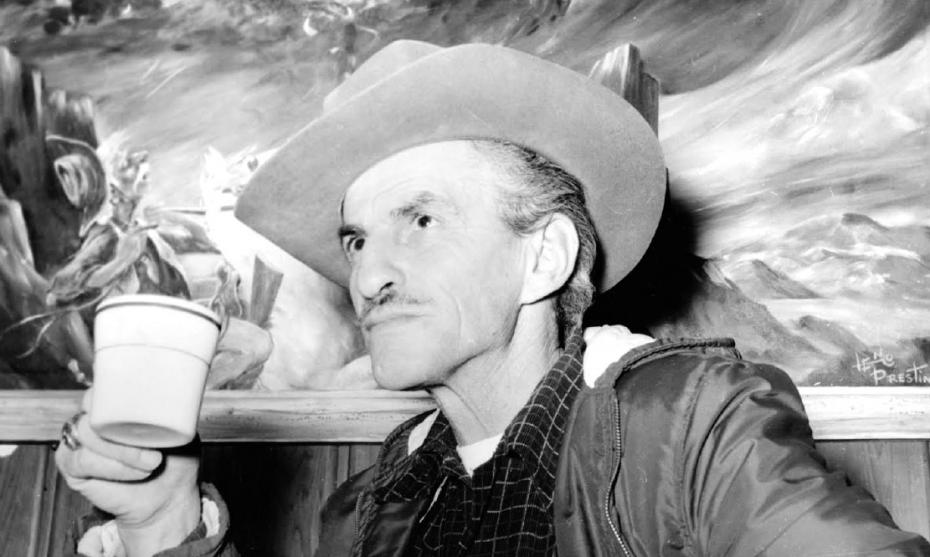

The story of Leno Prestini is inextricably bound up with the terra cotta factory and the tiny town of Clayton. His name is not well known today, but in the 1940s Prestini’s provocative, politically charged paintings made quite a stir. Although he was never able to take his art to the next level, this self-taught artist and sculptor created a substantial body of work.

The Prestini family emigrated from Besano in the north of Italy, first settling in the granite quarries of Vermont and later moving to Clayton. Luigi Prestini found work as a chiseler in the Washington Brick Company but died in 1919 from pneumonia. Leno and his older brother Battista dropped out of school to help support the family.

By 1925, the two boys were employed as piece workers at the brick plant. It was obvious from the start that Leno was artistically gifted. Within a year, he had advanced from terra cotta apprentice to chief modeler.

In a newspaper interview with the Colville Statesman-Examiner, Prestini explained how his career evolved. “At the plant in Clayton I learned to work with my hands,” he said. “An architect would make a rough sketch of an ornament for a building, an angel in flight, perhaps. But the detail would be up to me. Each man worked that way and so each developed his specialty in shaping the clay into figures.”

But building codes changed and the work started to dry up. “The other men started drifting away,” he said. “I did some drifting myself. And then I started painting.”

Leno’s “drifting” took him to Chicago and San Francisco. He tried his luck in Mexico and sailed as a mess boy on an oil tanker to Hawaii. He loved adventure, whether it was climbing mountains or panning for gold. He even built his own diving gear from an old hot water heater and a garden hose.

In 1936, he returned to Clayton, got a job in the brickyard and resumed his painting. Much of his art centered on the life he knew: Clayton’s brick plant and machine shop, the region’s sawmills and mining camps, its mountains and forests. He transformed these Northwest settings into paintings unmistakably his own, marked by a brilliant sense of color, dimensional depth, and a knack for the odd detail. His work stirred with energy and vitality.

As World War II neared, Prestini became more distraught by the news from Europe and his paintings reflected his emotional turmoil. One of his life-size paintings showed a futuristic battle scene where a cave man wrestled with a flame-breathing robot. He called it “Civilization–Page 1936.”

His next painting, “Page 1939,” took three years to produce. It was five huge panels depicting key players and symbols of World War II, including Neville Chamberlain and Benito Mussolini. The work was hung in the Clayton Café.

After painting “Page 1940,”Prestini took his series, now known as the Pages of History, to Spokane where they were installed in a stationery store window. The store manager, though, was forced to remove the paintings after just two days when passers-by complained about their graphic imagery.

Undeterred, Prestini traveled to Los Angeles with his paintings and attracted some media attention there. Interviewed by the Los Angeles Times, he told the reporter, “I’m no artist but I can’t help thinking.” The newspaper article opened a few doors for his “Pages of History” series. The paintings were photographed for a spread in Life Magazine, but the story never ran. Prestini claimed the article was killed because the editors did not want to offend European leaders.

In 1960, Gonzaga University hosted an exhibit of 50 paintings. Local critics praised his symbolism and vivid palette. “Leno Prestini may not be a trained artist, nor a genius in color and position, but there is more to art than outward form,” said Rev. Louis Ste. Marie, a Gonzaga professor. “Here is a man for all to understand and love, a man who has lived his life intensely, aware of the past and the present, of himself and of his fellow man.”

The exhibit toured to several cities in Washington state but Prestini seemed frustrated. In 1963, his brother Battista, living in Los Angeles, received word that Leno had been hospitalized in Spokane with a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He lingered for nearly a month but never regained consciousness. He was 57 years old.

Years earlier, Prestini had sculpted the figure of a two-headed mountain climber posed on the edge of a cliff. When Battista asked him about it, Leno replied: “Every time I get to the top of the mountain, my problems are still with me.”

Determined not to let his brother’s memory fade, Battista moved back to Clayton and built a small museum to display Leno’s work. In 1998, the family donated more than 70 paintings, sculptures, photos and documents to the Stevens County Historical Society. Eight paintings and some terra cotta sculpture are on display in the historical society museum in Colville, Wash. Loon Lake Historical Society has two Prestini murals on permanent display.