In this baseball season it is appropriate to celebrate Joe DiMaggio, who would have been one-hundred-and-one this year. One of the greatest baseball figures of his era, he played with grace yet power, creating records still unmatched by newer, better trained performers. But Joe DiMaggio gave this country something more. For all his prowess, his fame, the Yankee Clipper remained shy, an introvert. Yet without trying, without signing a single pledge or expressing a proud word, he broadened our understanding of who we were and are.

The first success was on behalf of his countrymen, Italian-Americans. Dimly recognized today, for long decades prejudice assaulted these immigrants and their descendants, from early riots in New Orleans to rancid portrayals in The Untouchables tv show. As young Frank Sinatra rose in the charts, Harry James asked him to change his name to something less ethnic, and the crooner bluntly refused. Pete Hamill wrote that DiMaggio and Frank Sinatra mattered because, by being the foremost stars in their respective businesses, they “changed forever the way Americans saw Italian Americans. For the first time, Americans with other…origins wanted to be like these children of the Italian immigration. And their accomplishments changed the way Italian Americans saw themselves.”

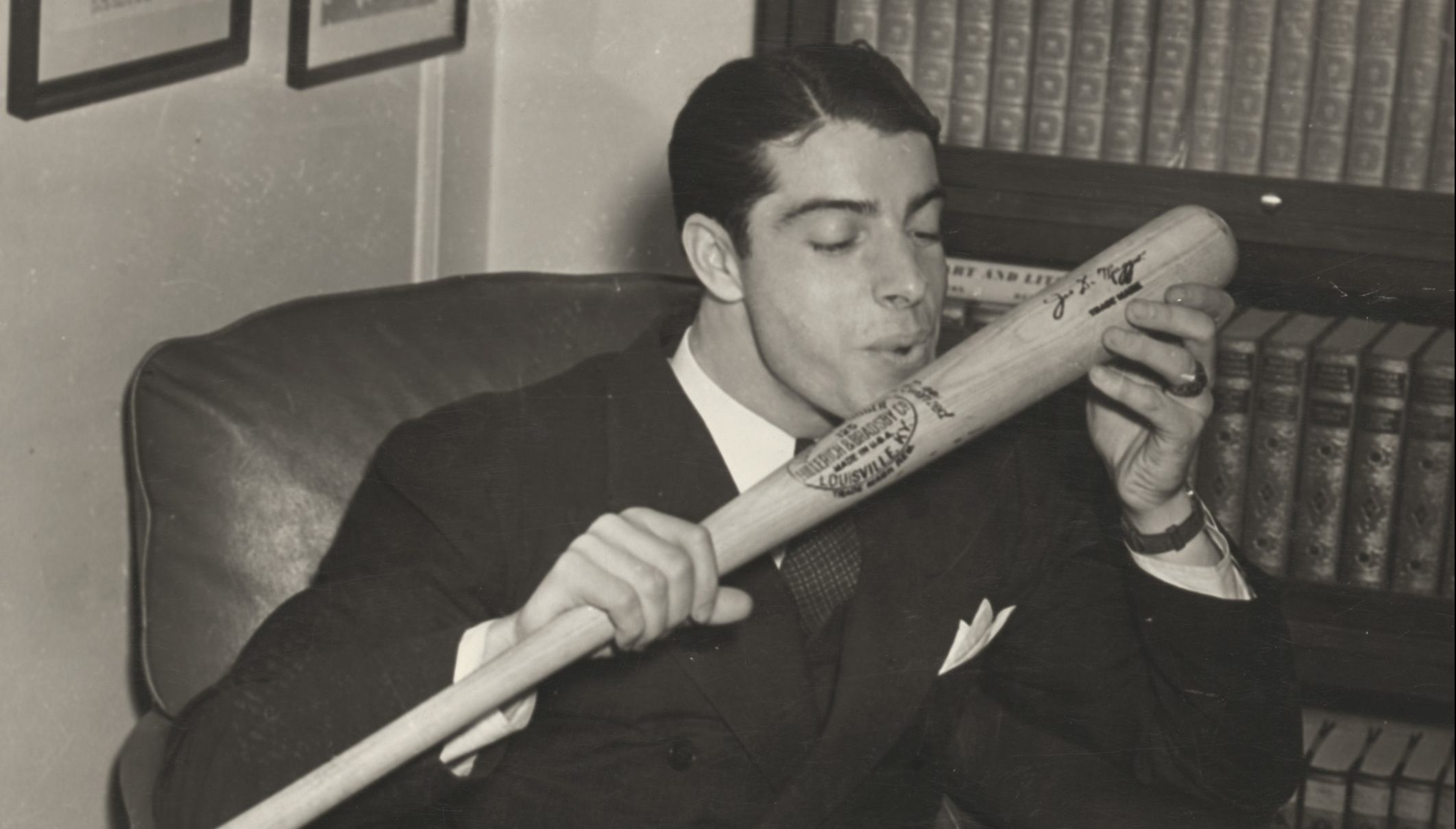

Important as that was, DiMaggio’s contribution went beyond those limits, to an entire generation of immigrants. Watch videos of him batting; he was a great hitter, and scored in 56 consecutive games, a record that, unlike Ruth’s or Gehrig’s, still stands. But there is something more, something quiet yet overwhelming. DiMaggio’s swing was an act of majesty, a ballet performance at the plate. That flow, that style, was his great achievement.

For with it, DiMaggio helped all newcomers, of all origins, rise in America. Basically put, he was the immigrants’ Fred Astaire, panache personified. His style captured beauty and refinement, not steerage. Hamill wrote that “DiMaggio was more than a baseball player; he was the epitome of grace, American grace.” And every other ethnic group in America knew this, basked in the reward, as they understood the effect he was having on the country, what he was teaching the original settlers without uttering a word. Jerome Charyn, a Jew, referred to DiMaggio as “our one immortal,” as “our first and last immortal star.” He was, as the great sportswriter Jimmy Cannon said, “one of the neighbor’s children” who was so gracious he made them all look good.

It is timely therefore, in an era in which the definition of mainstream American has expanded so dramatically, to praise a ballplayer who achieved those same aims by the strength and elegance with which he played the national pastime. Our thanks go to Joe DiMaggio for more than just baseball.

Robert A. Slayton is professor of history at Chapman University